In Baltimore County Public Schools, where I’m the purchasing manager, we’re underway on a strategic plan to prepare students for their chosen college or career path. We’re providing flexible, learner-centered, blended learning environments, including access to interactive curriculum for teachers, students, and parents.

Districts around the country are enacting similar plans, and many start by deciding on what technology to use in the classroom. At BCPS, we took a curriculum-first approach. We spent nearly two years talking to stakeholders and developing our instructional and academic goals before considering what technology to purchase.

Earlier this year, the board of education approved a $205 million contract for 150,000 devices for students, teachers, and other staff, in support of our 1:1 technology initiative. The purchasing process was also “curriculum-first,” involving teachers, principals, and even students when developing specifications for our acquisition.

For such a purchase, traditionally most K-12 school systems issue an Invitation for Bids (IFB), and accept a contract from the lowest-priced responsive and responsible bidder. It’s easy and usually doesn’t open the system up to protests or challenges from vendors based on the outcome. An alternative approach is the Request for Proposal (RFP), which is more complicated but based on factors that create the best value to the school district.

For our 1:1 Student Device Technology Program Initiative, we developed our criteria only after conducting device field tests with teachers, principals, and students across BCPS. These field tests proved crucial, especially those with students, a surprisingly overlooked stakeholder in the purchasing process.

Students were selected at random from elementary schools of varying demographics and asked to test different electronic devices by performing activities such as:

We were more interested in testing tablets than laptops and decided to focus more on the devices’ features than brand names. To select the devices for testing, we simply visited Best Buy and selected the eight that were on display. That way, we’d have a truly open and inclusive testing process. District staff recorded observations during the sessions and the students were asked questions about the devices at the end of the activities.

Overall, the students at all schools showed the ability to adapt to the hardware they were using. Students used both iOS and Windows operating systems, adapting to the nuances intuitively. Students were not afraid to try multiple techniques to accomplish tasks given. The differences in their behavior did, however, help us see what features mattered most.

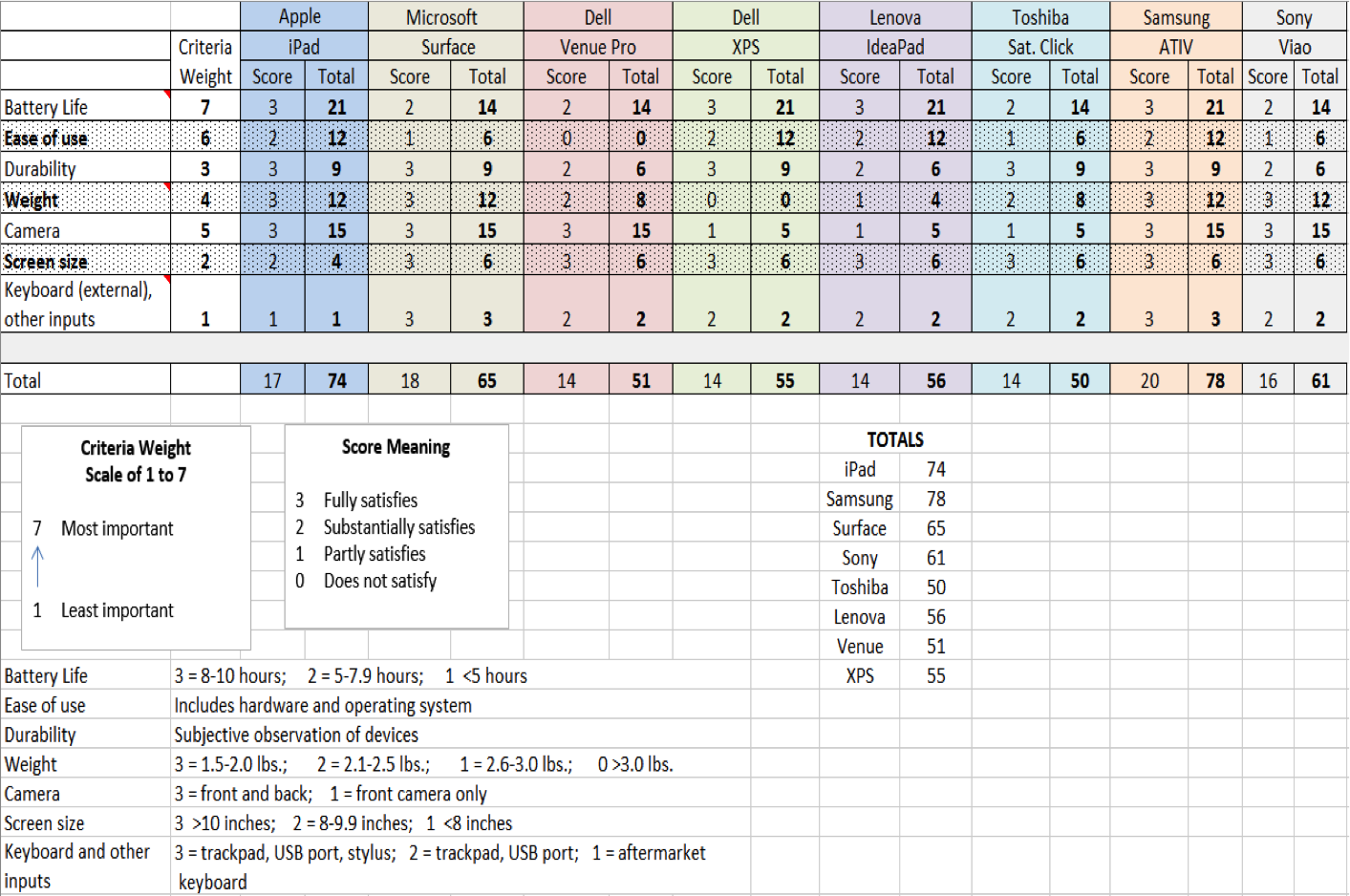

In all, seven criteria were used to evaluate the devices: battery life, ease of use, durability, weight, cameras, screen size, and keyboard and other inputs. The criteria were weighted on a scale of one to seven for relative importance. Student experience with the devices was a key driver for the scores, which are described in the table below.

These scores and observations shaped the development of our RFP. After we received the proposals and did an initial screening, BCPS evaluated and scored each respondent’s hardware, training proposal, deployment strategy, service model, and pricing. The vendor proposals for the 1:1 Student Device Technology Program Initiative were evaluated during two-hour oral presentations by a team of 17 individuals representing BCPS teachers, principals, staff from the Departments of Technology, Digital Learning, Purchasing, and Organizational Development.

The purpose of Blueprint 2.0 is to equip every student with the critical 21st century skills needed to be globally competitive. They need one-to-one technology and a personalized, interactive curriculum that extends educator capacity to differentiate instruction and provide timely feedback.

We had to make a $205 million decision on how to get there and we couldn’t have done so without the input of students, teachers, and principals.