The role of technology, the changing nature of the work force and the effects of globalisation means citizens and governments are playing catch up to make sure our future generations are capable and competent to perform the jobs of tomorrow.

Recent Australian studies show there’s a decline in student participation in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) subjects in high school. OECD data also shows we’re lagging behind high-performing countries like Singapore and Taiwan in literacy and numeracy.

We want more of our students to take up STEM in schools and universities so we have a steady stream of graduates skilled in these areas for the future.

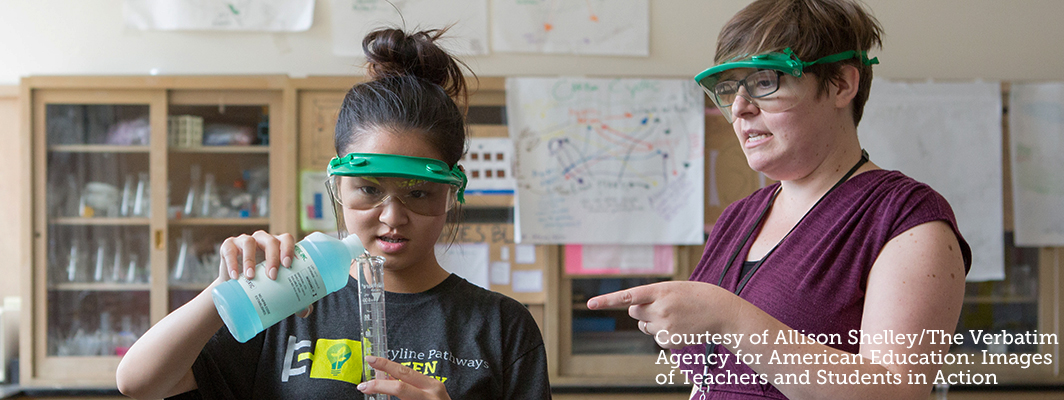

Teachers can have a strong influence on students’ engagement and interest in STEM subjects, and on how they view maths and science in terms of future careers. Research has shown students are more likely to be motivated and interested in their studies if they’re taught by effective and inspiring teachers.

Teachers have to be STEM literate and confident to teach competently and bring a real-world application of expertise to the classroom.

Currently, there’s a shortage of qualified maths and science teachers in secondary schools. Often, teachers who are qualified lack the knowledge or experience of how these disciplines are used and valued outside of school. Those coming to teach straight from university don’t have the capability to link theory with practice. Nor can they see the connection between STEM subjects taught in schools and their applications in the real world.

This means students don’t get the full appreciation and knowledge of science and mathematics teaching in practice. This can lead to disinterest and disengagement, resulting in fewer students taking up STEM subjects in senior years and in university.

Teachers who have been STEM professionals prior to becoming teachers bring invaluable work and life experience skills to the classroom.

People who have worked in STEM areas outside of the teaching profession, such as mathematicians, technologists, engineers or scientists, have current knowledge and experience of the discipline. This enables them to effectively demonstrate the link between content knowledge in maths and science, and its diverse uses in real workplaces.

They can act as role models and are able to engage students by helping them to develop a broader understanding and interest in STEM areas and opportunities. Science and maths become more interesting and relevant to students when they’re able to see the connection between key concepts and its practical application. Bringing the field experience into the classroom sparks passion and interest.

Research reveals this mature-age cohort also exhibit self-confidence, creativity and passion. Skills such as these fall under the scope of “inspirational teaching and inspired learning”, as indicated in the Chief Scientist’s 2014 report Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics: Australia’s Future.

Career changers are intrinsically motivated and tend to be more committed to teaching. While there are several factors influencing their choice to change careers, research indicates their commitment stems from making a conscious decision to become a teacher.

Recent research conducted among career-change student teachers has shown there’s a growing number of career changers, including scientists and mathematicians, who join the teaching profession.

STEM career changers can make science relevant to students by using examples from their own lives. They can help students see the value of reasoning and attention to models embedded in scientific practice. We need more of these experts if we’re to build the capabilities of STEM-skilled graduates for Australia’s future workforce.

While we know career changers in general are highly motivated and bring invaluable skills to the classroom, little academic research exists on STEM professionals who are teachers. A closer look at this group of teachers is required to understand their motivations and contributions, teaching style and classroom approaches, and their ways of linking theory and practice.

It’s also imperative we understand the various barriers and enablers they face as STEM teachers. Research on career changers indicates some of the barriers relate to a lack of recognition of their experiences by school staff. They also face challenges associated with translating some of their STEM skills to classrooms. Appropriate support systems to ease their career transition and a better awareness of their strengths could go a long way.

![]() We need to talk to these teachers so we know what factors contribute to their success (or failure) in the classroom. This will enable us to take the necessary steps to make the teaching profession more attractive to professionals from STEM fields.

We need to talk to these teachers so we know what factors contribute to their success (or failure) in the classroom. This will enable us to take the necessary steps to make the teaching profession more attractive to professionals from STEM fields.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.