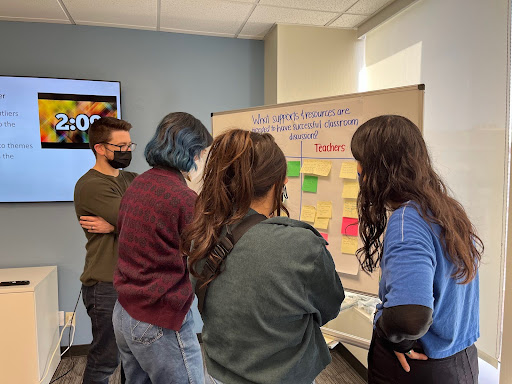

World history teachers discussing the supports & resources needed to implement classroom discussions

For the past year, the Digital Promise team has hosted a cohort of twelve high school teachers and eight researchers to design Deeper Discussions in World History, with a goal of improving facilitation and discussion challenges in history classrooms. In this blog post, we share how we have applied Dr. Gholdy Muhammad’s Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy to our discussion-based lessons and attempted to center student experience in the process.

Rather than focusing exclusively on skill and knowledge development, Dr. Muhammad’s four-layered equity framework expands the definition of literacy to include the pursuits of identity development and of criticality, which Muhammad (2020, pg. 120) defines as “the capacity to read, write, and think in ways of understanding power, privilege, social justice, and oppression, particularly for populations who have been historically marginalized in the world.” As our high school world history teacher cohort has attempted to incorporate these ideas into their lessons, they’ve taken the following approaches:

Identity

In the context of world history class, supporting students in understanding their identity (and identities of others they care about) can mean designing discussions and selecting texts in ways that:

For example, students studying the Neolithic Revolution discuss the ways that the shift to sedentary agriculture impacted all aspects of human life (e.g., the types of jobs a person might have, what they would eat, how they would relate to their community, their gender role, how they would spend their free time). Students answer the question “would you rather have been a hunter-gatherer or a farmer?” In doing so, they are called on to clarify their own values, and the types of trade offs they would be willing to make in their own life.

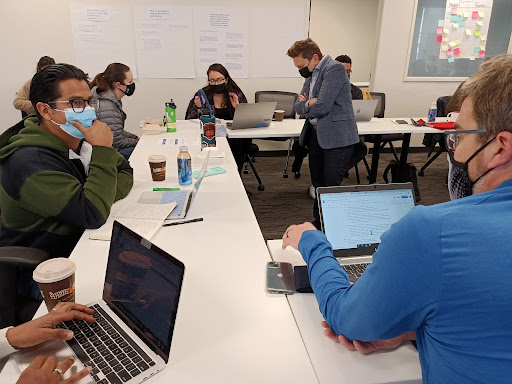

Our cohort convening in Digital Promise’s California office during a roundtable discussion

Criticality

Discussions in world history classrooms that aim to support students’ pursuit of criticality can ask them to:

For example, when studying the Ghanaian Independence Movement, students contemplate dynamics of power involved in determining how an event is remembered or memorialized. Taking on the role of a sculptor hired to create a memorial to Ghanaian Independence, they sketch a proposed memorial, and discuss decisions about who and what to represent in their sculpture, and what should be given more or less prominence. This activity leads to a class discussion on how history is created.

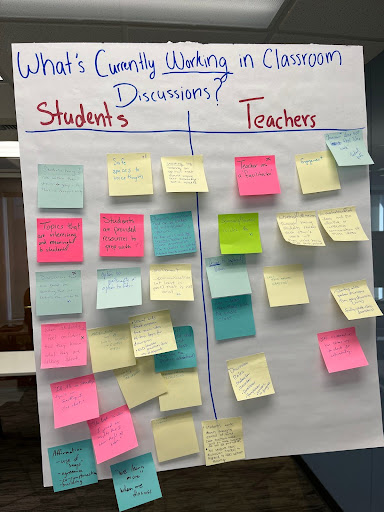

Members of our teacher cohort write, share, and reflect on what’s currently working in their classroom discussions

While one of the core tenets of this project is about creating world history discussions that incorporate the pursuits of culturally responsive teaching, it was also important to gain an understanding of what is culturally relevant to students, and for that we needed to ask students themselves.

Before delving into the curriculum design, members of our teacher cohort engaged in empathy interviews with their students, revealing valuable insights. Notably, students expressed a dislike for forced participation and a desire for meaningful, relevant discussions with low-stakes entry points. Their ideal discussions were characterized by safety, comfort, ample preparation time, scaffolding tools like visual aids, and feedback and affirmations during conversations.

Building on these insights, we developed protocols to encourage exploration of identity and critical thinking among students. Based on subject-general questions suggested by Muhammad (2023), we co-developed subject-specific questions that related to identity and criticality.

Examples of Probing Questions about Identity

Examples of Probing Questions about Criticality

Our team designed a post-discussion survey to delve deeper into student experiences during discussions. We hope to use these tools to add new dimensions to our design and reflection process, and provide insights into how well a lesson connected with students’ lived experiences and its relevance to their day-to-day lives.

Our commitment to co-designing culturally responsive and relevant curriculum for world history classrooms that centers student experiences, fosters criticality, and embraces diverse identities, is exemplified in the thoughtful approaches our teachers:

“When I think about joy in the classroom, it is almost exclusively discussions. [My students] like seeing someone who likes to talk, without [the teacher] tamping it down. Letting them talk in the ways that they talk… Knowing what students are interested in helps bring out joy.”

-Erin Mandzak-Heer

“Culturally responsive pedagogy should exist everywhere in one’s classroom. To this point, my classroom is a warm and safe environment for students to voice their opinions, questions, and to take risks. Student representation in the classroom is important in creating this environment…Building positive relationships and trust are essential to creating a classroom where students can feel comfortable and therefore learn.”

-Daryn Cohen

To stay up to date on the Deeper Discussions in World History project, subscribe to the Learning Sciences Connections newsletter!