December 4, 2023 | By Alison R. Shell and Jessica Jackson

As many districts begin to adopt the POG as their new end goal, we have to truly understand how these 21st century skills develop in a learning context. Our new Portrait of a Learner (POL) model on the Learner Variability Navigator (LVN) synthesizes research across many fields of research including psychology, cognitive science, learning sciences, and education research in order to 1) understand how these 21st century skills develop from the start of schooling to graduation; 2) understand how they vary across learners and contexts; and 3) recognize how they are tightly connected to core factors of learning across a whole learner framework. It is the ultimate exercise in backwards design for the whole learner.

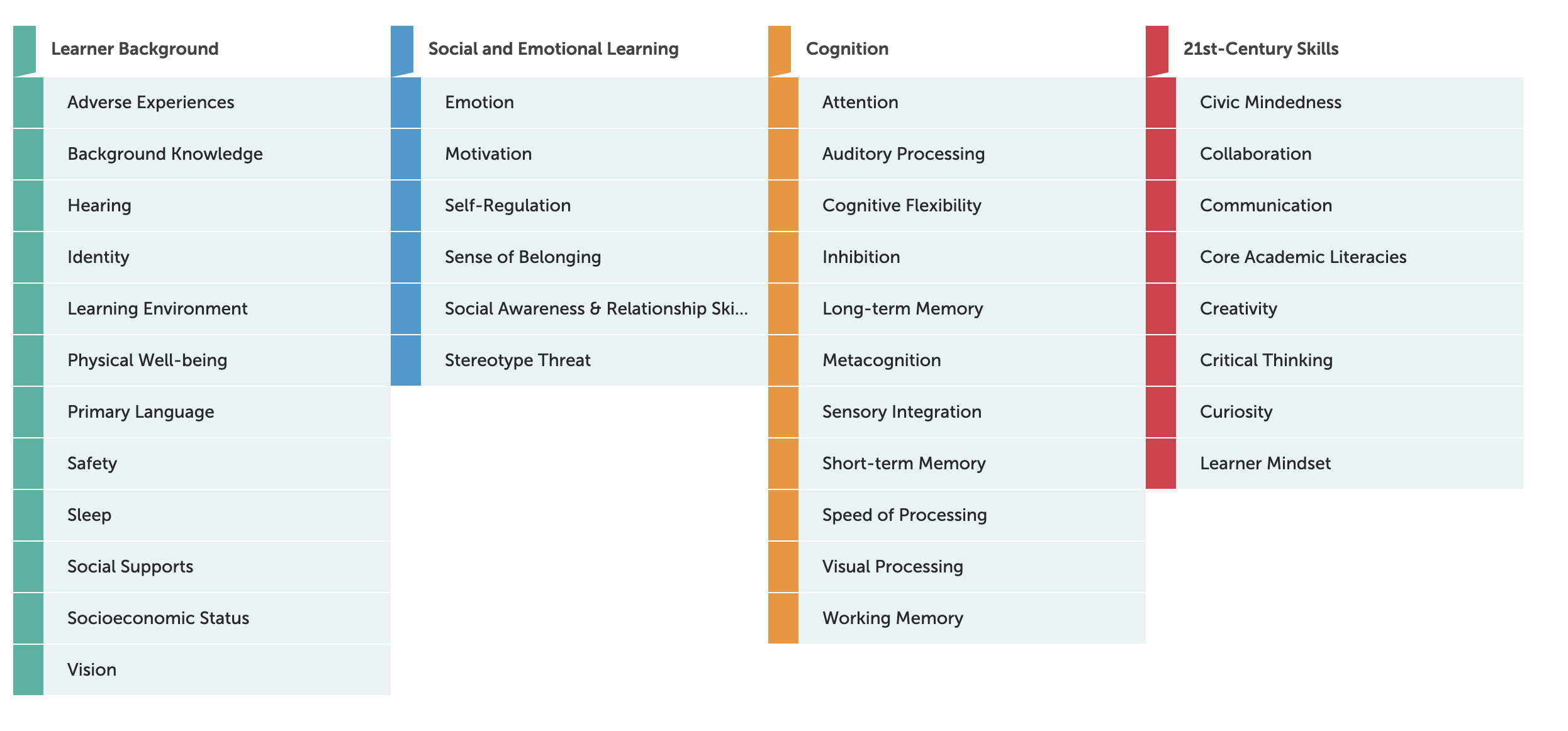

A whole learner framework depicting key factors of learner variability from the Learner Variability Navigator.

The LVN is a free and open source tool that showcases how learner factors, or individual variables, work together to affect learning (see framework above). The 21st century skills in the far right column of the framework reflect the skills of learning and success within and beyond the classroom, which have been highlighted in many of the POGs adopted by districts. Crucially, this tool has been developed through a rigorous research process, grounding these concepts in learning sciences, and showcasing how they connect and interact across the whole framework. The POL models are broken down into three developmental stages from grades PreK-3, 4-8, and 9-12. We use the science of learning to consider key relationships and developmental changes in the brain and body, social and environmental context, and classroom culture and structure to gauge how to truly understand and support our learners, and ensure that every learner has the skills and tools to embody the POG.

As we developed the POL models, a number of themes emerged from the research that provide insight into how these 21st century skills develop and also how they are intertwined. Understanding these themes is critical for backwards mapping from the POG to designing for the whole learner.

As learners continue to explore and ask questions, they use critical thinking and reasoning to investigate increasingly complex questions about how the world works. As learners’ cognitive skills develop through adolescence, their critical thinking skills develop as well, especially when these skills are explicitly taught and supported. These include an increased ability to think abstractly, use logic, and consider hypothetical scenarios or ideas. Critical thinking involves many reasoning processes and cognitive skills that are important for preparing learners for their future roles as active, participating members in society.

A learner’s civic identity is grounded in having a sense of self as part of a larger whole. Exploring their identities and values is key to guiding their actions in their communities, and developing civic-mindedness. Even young learners are capable citizens, engaging with their home, class, and local communities. As students become more confident in their ability to engage and act on social issues, they can also become more empowered as individuals and involved in their learning. Encouraging students to consider their own needs, and promoting self-advocacy can support their sense of self, and their civic-mindedness. Providing students choice over different aspects of what and how they learn promotes their sense of agency in the classroom.

Across all these core factors of 21st-century learning, we see the critical element of a need to feel safe and secure in order to try new things, share perspectives, explore identities, make mistakes, advocate, and engage, all of which require a sense of belonging. Belongingness is the extent to which students feel personally valued, included, and supported by others in their learning environment. Research suggests that teachers have a unique opportunity to promote belongingness, because teacher support is one of the strongest predictors of learners’ sense of belonging. Culturally-responsive teaching practices can help all students feel respected and valued in the classroom, including validating students’ varied background knowledge and lived experiences, identities, and ways of knowing.

When we look at the Portrait of a Graduate, we have a sense of who we want our learners to become, but the Portrait of a Learner is our guide to understand who our learners currently are. When we work backwards, we are able to see both, and design a pathway for success. The POL shows us why whole learner approaches matter for developing students who can thrive in the 21st century economy and society. Who we are is inextricably intertwined with how we learn and how we connect to our environment. Taking a whole learner approach includes designing learning that takes into consideration how we learn across development and contexts, recognizes and affirms students’ strengths across the whole child, and provides opportunities to leverage those strengths within a joyous, safe, and supportive environment that fosters deeper learning.

By Sharin Jacob and Quinn Burke

By Dr. Kyle Dunbar and Katie Wilczak