Susan Adelmann is vice president of strategic partnerships at Follett School & Library Group, a corporate supporter of Digital Promise. This blog post is part of a series that highlight different stakeholders’ perspectives on purchasing practices for K-12 personalized learning tools. Also be sure to check out our procurement study: Improving Ed-Tech Purchasing.

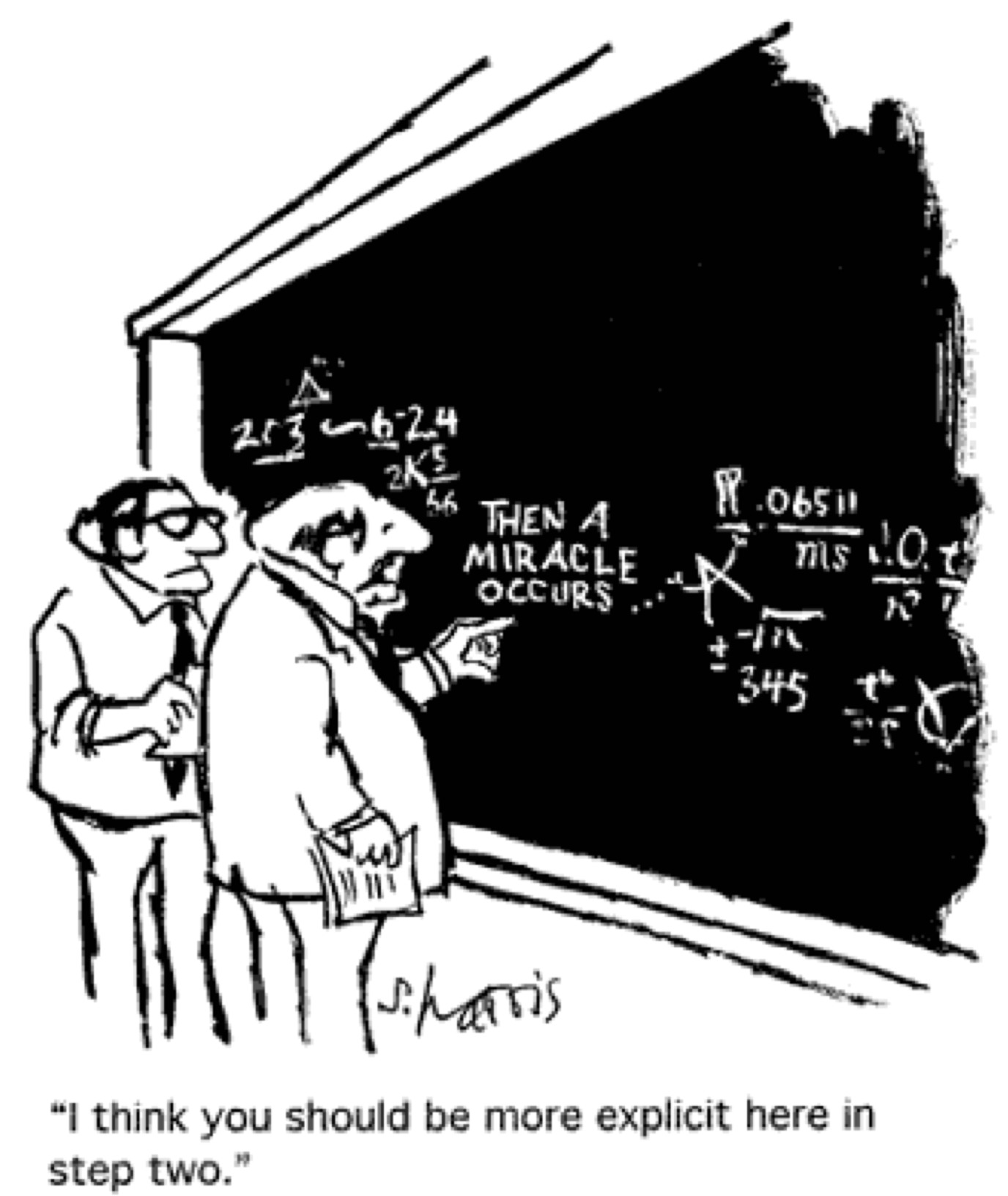

When I think about how the adoption and acquisition of technology is changing in K-12 education, it brings to mind the well-known Sydney Harris cartoon.

I’ll bet you’ve seen it. It’s one of my favorites.

I’ll bet you’ve seen it. It’s one of my favorites.

It’s about the tension between the passion and creativity of what might be possible (the “miracle”) and the security, safety, and certainty of what can be absolutely known (the science of a formula). It’s a reminder both of how the quest for a definitive answer can stunt innovation and how failure can be inevitable without enough planning.

In other words, it’s an apt metaphor for the changing circumstances facing K-12 schools looking to acquire and adopt technology and digital learning resources. Those circumstances have led to two interesting tensions emerging, which mirror those evoked by the cartoon:

A tension between the desire for learning tools and pedagogies that are proven to be effective and those that are recognized as innovative.

A tension between our comfort with traditional top-down, structured adoption and discomfort with loosely governed, bottom-up innovation fueled by teacher explorers and (ready or not!) the technology in our kids’ pockets.

As an industry, we don’t know enough about how these tensions will play out to fully proscribe best practices for acquiring personalized learning technology and resources. But, in recognizing these tensions, we know enough to suggest some next practices emerging in adoption and acquisition.

1. Take a “learning ecosystem” approach to ed-tech acquisition

One emerging practice that seems to be sticking is the shift away from piecemeal financial planning— devices vs. content vs. professional development—toward more holistic planning that addresses all of these products, services, and decision-makers together, as a “learning ecosystem.” That’s when districts think in terms bigger than technology, bringing together plans for strategy, technology, instruction, and curriculum.

As state and district guidelines for instructional materials spending began expanding to include technology, we initially saw a pattern of early adopters diverting most or all available dollars toward devices. Devices were purchased without fully addressing how and what learning resources would be used. It became very easy to say, “There’s an app for that”, and not plan much further.

Collective wisdom seems to now be telling us that shifting funds entirely to one-to-one devices without more comprehensive planning across the whole learning ecosystem is short-sighted—perhaps a little like the miracle in step 2 of the cartoon formula. We can’t gloss over these important questions:

What resources for which students?

What teacher supports are needed?

How do we mitigate the risks that come with shiny and new products?

How does all this work together?

This is a big shift. Schools are not used to acquiring technology that accounts for the whole ecosystem: mobile devices, curriculum framework, learning resources, technology infrastructure, and instructional support. But, where this is happening, it is successfully shortening the distance to return on education investment.

2. Harnessing teacher-driven innovation, including small-scale pilots

I’m consistently blown-away by educator innovators who are fully charged with the passion and energy to discover and adopt the tools that work best for their students. And equally amazed by watching what happens when students are invited to be part of the learning innovation process.

Can our next practices in acquisition and adoption harness this bottom-up energy? Absolutely. Can classroom-level digital learning pilots embrace experimentation, limit risk, bake goals into early adoption, and lead to meaningful scale across the district? Can the ability to learn from smaller wrong-turns be baked into the learning process itself?

Some great patterns are emerging for the kinds of iterative adoption methods that prioritize the entry of new technology, resources, and pedagogy through teacher-driven pilots. The beauty of this kind of “local empowerment” is that it naturally encompasses the whole learning ecosystem and leverages educators’ instincts to measure success student-by-student as learning occurs.

The tensions we face in a changing industry aren’t necessarily prohibitive. They can spark interesting new possibilities in how to acquire, validate, and scale up better classroom tools, technology and instructional practices for deeper learning. No miracles required.

Photo: “And then a miracle occurs.” by jpallan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0