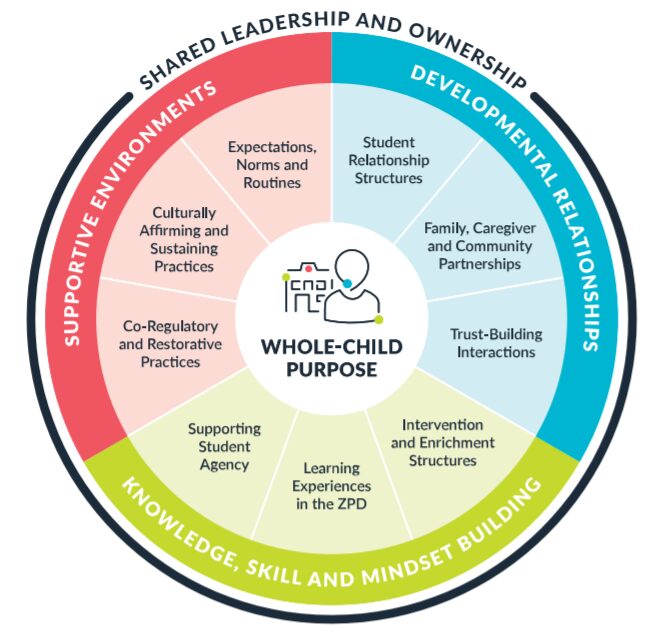

Whole Child Design Blueprint, courtesy of Center for Whole Child Education

Considering the whole child—their strengths and challenges in academic and cognitive areas, social-emotional skills, and specific background factors, such as health indicators—requires educators to understand and address children’s learner variability in order to help young learners reach their potential and achieve a sense of well-being and confidence. In essence, a whole child education approach strives to ensure that every child is healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged. It acknowledges that a child’s ability to learn is influenced by multiple developmental domains. Understanding learner variability leads to personalized and strength-based instruction to meet students where they are. It also recognizes the plasticity of a young child’s brain and how context can have an impact on a child’s learning and development.

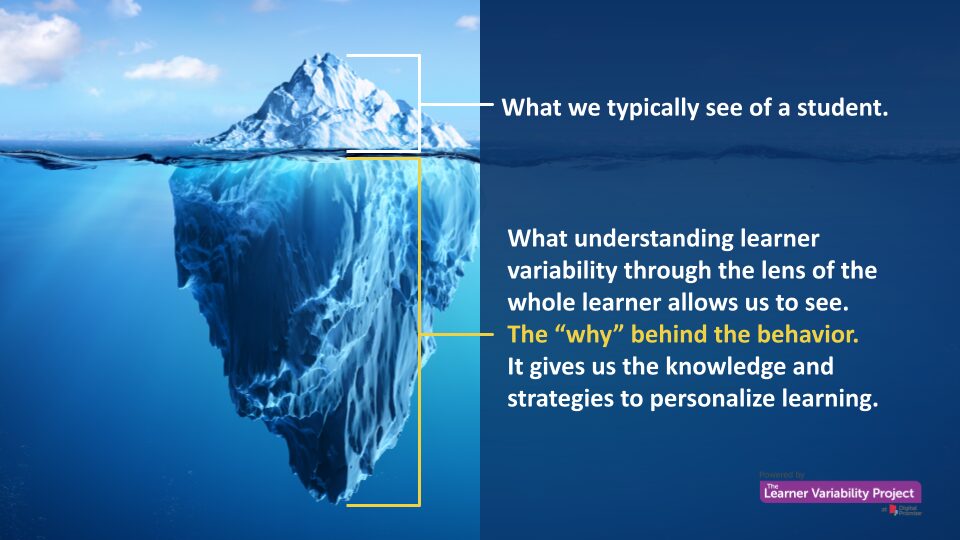

Envision the iconic iceberg image. The tip, situated above water, is what we see in a young learner’s behavior. They may be engaged in a task, giggling with a friend, distracted, or charging around the room. When we understand learner variability through the lens of the whole child, we better understand what’s below the surface that can impact learning and classroom engagement. By building relationships with the child and their family or caregiver, an educator may recognize distraction as a possible reaction to a family member’s job loss, which could affect the family’s socioeconomic status. The trauma of economic hardship can affect learning and academic achievement. It can also impact other aspects of learning, such as vocabulary, cognitive flexibility, or emotional development. In other words, it can affect the whole child.

Thus, addressing the full scope of a child’s development rests on the interconnection of physical, social, emotional and cognitive growth with academic learning and a school environment that is safe and emphasizes belongingness. “It is literally neurobiologically impossible to think about things deeply, or remember things, about which you have had no emotion,” said Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and Antonio Damasio in “We Feel Therefore We Learn” (2007).

Cognitive development, for example, recognizes that students process, understand, and express learning differently due to variability in working memory, executive function, and attention. Social and emotional development fosters a sense of belonging, resilience, and self-awareness. It also teaches self-regulation, collaboration, and responsible decision-making—skills essential for both school and life. Psychological well-being recognizes that mental health, trauma, and stress affect learning. It supports a growth mindset, encouraging students to embrace challenges as opportunities for learning. A learner’s physical health also plays a role, as sleep, stress, and overall wellness affect both learning and behavior.

Home learning environment, a factor identified by Digital Promise’s Learner Variability Navigator (LVN) research as important for learning, is key, especially during early childhood. During this time, the majority of learning occurs in the home. Children learn their primary language here, learn how to communicate and understand others’ emotions. Setting up a school program to bridge home and school learning is a plus. For example, rich background knowledge that develops in the home can be cultivated as a student’s strength and can guide in book selection and the creation of activities.

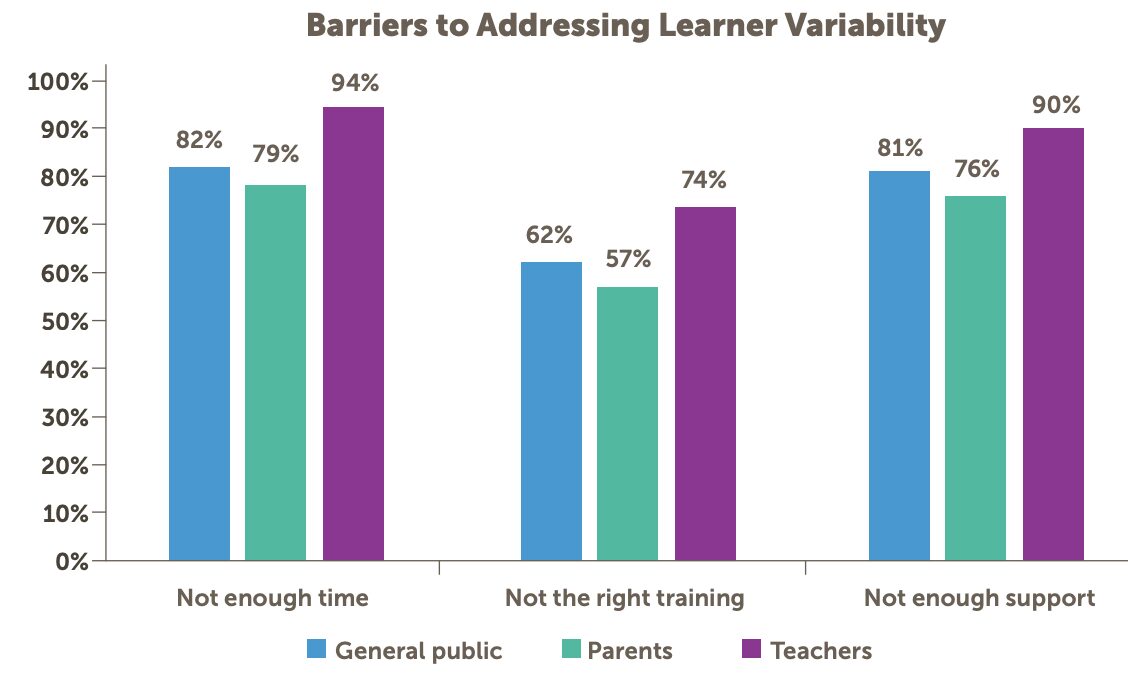

All of the factors of learning in LVN’s whole child framework interconnect and create a portrait of a whole learner, an understanding of which teachers can apply to designing their instruction and space. Yet, teachers cannot do this alone. A Learner Variability Project survey found that while American public school teachers, parents, and the general public overwhelmingly say school should work with individual learner variability, several barriers to doing so exist. Time, support, and a lack of professional training are three huge barriers all survey participants say impede bringing learner variability to the classroom.

In order to bring learner variability to classrooms, districts, and schools need to provide appropriate learning experiences for teachers that focus on understanding and applying learner variability across a whole child framework. To address challenges related to a lack of time and capacity, a serious rethink of how the school day is organized is required—a day that provides teachers with enough time to get to know their students’ academic and cognitive needs, but also their social and emotional skills (essential for the workforce, according to the World Economic Forum, as well as each student’s unique background and how it can be used as a strength and as a guide to what strategies may or may not work for them. Teachers also need time to examine student data to make informed decisions on which strategies to put into play in their lesson plans. Families should be seen as partners in education with meaningful involvement in the school life of their young child. Family engagement workshops should encourage families and caregivers to participate.

What does whole child teaching and learner variability look like in a classroom? Sarah Carranza, an elementary and world language instructor at Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton College for Teaching and Learning Innovation, shares her framework called BFF in this webinar:

In a whole child classroom that honors learner variability:

There are multiple reasons why whole child education and learner variability matter in designing classrooms that promote growth and belonging for each young learner. Together they shift us from a one-size-fits-all approach to flexible and personalized learning based on learner variability. Learning that is informed by a holistic approach and understanding of learner variability prepares students for life beyond the classroom by fostering resilience, creativity, and critical thinking. They also ensure that each student, regardless of background, ability, or learning profile, can thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

A whole child approach isn’t just about what students learn—it’s about who they become. “When you understand learner variability, you see a design challenge, not a student problem.”