“While they’re here, we’re the ones that they’re counting on. We’re the ones that provide their reinforcement, the safe place, the continuity. When they go home, they may not have that.”

– Amy Creeden, principal and Race to the Top lead

The majority of K-12 students in the U.S. now live in poverty, a mark hit in 2013 for the first time in 50 years, according to the Southern Education Foundation. For these students, poverty brings a host of other disadvantages, most beyond the school district’s control: broken homes, transient living situations, and a lack of educational support at home. Between 30 and 40 percent of students enter kindergarten not ready for school.

It may seem like the deck is stacked against schools that predominantly educate low-income populations. Once they start their education, those students have a wider variety of social and emotional needs and receive less educational enrichment outside of school. And when those students struggle to catch up academically, they risk falling even further behind their peers.

One district facing that very challenge is Middletown City School District, a member of the Digital Promise League of Innovative Schools. Middletown is about 70 miles northwest of Manhattan. Seventy-five percent of students live in poverty, half are Hispanic, and a quarter are African American.

It’s a place that many families move to from New York City, where effects of poverty like drugs and violence are more visible. In Middletown, those effects are more subtle, resulting in, as 6th-grade teacher Brandi Hundley says, “struggling families that are trying to do the best they can — working hard but [without] the privileges that others have.”

More than a decade ago, the district seemed helpless against the educational effects of poverty. About half of its students did not complete high school and all seven of its schools were classified by the state as “in need of improvement.”

Middletown School District, a #DPLIS member, works to erase the look and feel of poverty: https://t.co/OcFbxT9ygG pic.twitter.com/QuZSJy3xw1

— Digital Promise (@DigitalPromise) February 9, 2016

To turn things around, Middletown decided to go beyond the school district’s traditional role in addressing poverty, and tackle it head-on. Its ambitious goal is to “erase the look and feel of poverty” in its schools, as Superintendent Ken Eastwood puts it.

Richard Del Moro, Assistant Superintendent of Curriculum and Instruction, adds that Middletown works hard to make their students “feel good” by providing opportunities beyond academics, including extracurricular activities, athletics, music, and the building environment. Why does that matter? According to Del Moro, “a building that feels welcoming and inviting makes you feel good about being in that environment.” As a result, students engage in academics, athletics and extracurriculars because they “know you care.”

All of these efforts are setting the groundwork toward a concrete goal. Eastwood wants each student to be proficient in math and reading before finishing 5th grade.

All of these efforts are setting the groundwork toward a concrete goal. Eastwood wants each student to be proficient in math and reading before finishing 5th grade.

The district is working toward this goal through a wide range of bold initiatives, which include offering two years of kindergarten, ending “social promotion,” connecting every student to technology, and putting significant resources into athletic facilities and music programs.

“We want our kids to have the same opportunities as any other student, regardless of their zip code,” says Eastwood, who is in his 12th year as superintendent.

The district believes that by making its students feel equal to those in more affluent communities, they will start to see the same outcomes. That even if no one in these students’ families attended college, they can be different.

Though the rate of low-income students in the district has steadily increased in the last decade, so have graduation rates, to 83 percent in 2014.

The rest of the country is starting to pay attention as well. In 2012, the district was one of 16 U.S. districts to earn a $20 million federal Race to the Top grant. That grant is a large bet that Middletown’s progress is real, and that it will not only continue, but become a model for other districts educating low-income students.

“I’m not there like I feel like I should be.”

– Celeste Miller, Middletown parent

Celeste Miller is a single mother who works from 3 p.m. to 11:30 p.m, often six days a week, at an auto manufacturing plant in Rockland. Her commute from Middletown is more than an hour each way.

Celeste’s son, Karim, just entered the 7th grade. Miller is like many parents in Middletown: working long hours to support her children, but forced to be absent in the process.

“Although I’m not hanging out, I’m not partying, it still does not erase the fact that sometimes it makes me feel less than a mom,” she says.

When Karim returns home from school, Celeste has already left for work. He spends a couple hours by himself, making snacks, doing his homework, and playing video games. He is eventually picked up by Celeste’s cousin, who lives in Middletown and takes him to the local teen center for a couple of hours. The cousin later picks Karim up and brings him to her house, where he eats dinner. He goes to sleep on the couch around 10 p.m.

Sometimes Celeste returns from work as late as 3 a.m., if she works overtime. When she gets home, she picks up Karim at the cousin’s house, takes him home, and puts him back to bed. At that point, Celeste takes a few hours to unwind, wakes Karim up again around 7 a.m., and sends him off to school. She then goes to sleep until around noon, when it’s time for her to get ready to go to work.

On Sundays, Celeste’s day off, they do whatever Karim wants, usually going to the mall, or a movie, or an entertainment center for kids.

“I feel guilty because he just does not have a normal life,” Miller says. She explains: “The bills — they’re not going to stop coming. You stop working, they don’t stop coming. But I watched my mom do it and that’s what gave me the drive to do it.”

“There’s always someone’s situation out there that’s worse than yours,” she continues. “I try not to complain. I have a job. I have a roof over my head. My child, basically he wants for nothing. I try my hardest not to complain, not to get upset. I just do it.”

In school, Karim is a solid, determined student who still struggles in some areas. Brandi Hundley, one of his teachers last year, knew about his mom’s work schedule. Like a few other students of hers, Karim would spend his lunch period in her classroom, where she would give him some extra academic help. Hundley describes him as a positive person, obsessed with food and something of a jokester, though more reserved around people he doesn’t know well. He loves technology and is often the one to help other students (and teachers) with any technical difficulties in class.

Many teachers in the Middletown school district play many roles beyond teacher. They can be the guidance counselor, social worker, friend, parent, and grocery shopper or more, depending on the student and circumstances. A prevailing sentiment among the teachers is how impossible it is to effectively support students in the classroom while ignoring what happens once they leave.

“Most of what our staff does is show up committed and dedicated — they really take care of these kids and make sure that they’re safe, that they’re healthy, that they’re happy, they’re eating, they have clothes,” says Amy Creeden, an elementary school principal.

“Most of what our staff does is show up committed and dedicated — they really take care of these kids and make sure that they’re safe, that they’re healthy, that they’re happy, they’re eating, they have clothes,” says Amy Creeden, an elementary school principal.

Compared to white and affluent students, low-income and minority students have less access to nearly every type of educational benefit.

“It’s basically kids raising themselves in some of these scenarios,” says Creeden.

Middletown isn’t the only district fortunate enough to have faculty who go above and beyond their job description to care for students. But for a traditional public school district, the breadth of its work to reduce the educational effects of poverty is extensive.

Well before the Race to the Top grant, Middletown tested its theory that if students feel good about their school environment and are engaged outside the classroom, academics can improve.

That means spending $140 million in capital improvements during Eastwood’s tenure, so that school buildings, athletic facilities, and amenities rival that of more affluent districts.

A new elementary school, Presidential Park, hosts more than 1,000 students in a modern, state-of-the-art building. All schools are equipped with high-speed Wi-Fi. Eastwood often fondly recalls when Middletown High School’s newly renovated stadium hosted a regional track meet. When a bus carrying students from a wealthier neighboring district pulled up to the stadium, Eastwood could hear them marvel, “How did they get that?”

Early in Eastwood’s tenure, he was told the district didn’t offer a strings music program because it’s “not our kids.” With the belief that extracurricular activities can improve academic outcomes, the district launched a program the following year for third- and fourth-graders. Instruments were free and students could keep them year-round.

“Our children, because they come from homes of poverty, are cultured into avoiding anything that costs money,” Eastwood says.

With no barrier to entry, more than 225 students enrolled for the first year. Eight years later, there are nearly 700 participants, some of whom have performed in statewide symphonies.

Several years later, the district noticed a similar opportunity for its partnership with Syracuse University. High school students could take college courses in Middletown with a certified adjunct professor. Three-credit courses were $1,200 each, a major discount, but only about 50 low-income students were participating.

Using what it learned from the strings program, the district decided to offer courses for free — with the help of its Race to the Top grant. Enrollment skyrocketed to nearly 300 students.

“That’s always the fear as an educator that I have: What if this child goes onto the next grade level and they’re not quite ready? Do we send them along and just let them struggle?”

– Raquel Parker, kindergarten teacher

In Middletown, students come to kindergarten with a wide range of academic skill levels. Some haven’t attended pre-school, others have not started developing literacy skills, and many live in households where English is not the first language.

“Just because you’re five years old doesn’t mean that you’re ready for kindergarten,” says Creeden.

This is a huge challenge for kindergarten teachers but it can also become a challenge for first-grade teachers, then second-grade, and so on. Research shows that students who enter school lagging behind their peers struggle to ever close that gap and, in most cases, will find it widen over time.

To address this challenge, Middletown offers incoming students who are significantly behind their peers two years of kindergarten before they enter the first grade. The goal is for students who may not have had any previous formal education to catch up as quickly as possible to those who have.

Class sizes are kept low, and students remain with the same student cohort. Students are not “repeating” the grade in the traditional sense, going through the same lessons a second time. Instead, teachers, aided by learning software, determine students’ strengths and weaknesses and tailor activities toward them.

That kind of close attention is not possible in regular classes, and it’s not something children are necessarily getting outside of school, says Raquel Parker, who transitioned from teaching regular kindergarten to two-year kindergarten.

“We definitely do try to go that extra step to make those children feel just as comfortable and just as supported and let them know, ‘You can be successful even if you don’t have the same stuff at home that another child has,’” Parker says.

The program’s first cohort entered the first grade this year. Nearly all students are above grade level and some started ahead of their peers from regular kindergarten.

While it’s still early on, Middletown can envision a learning environment in which all students can develop grade-level skills before they are even cognizant of the interventions helping them do so. In that ideal world, costly remediation in middle and high school is less necessary and all students have a pathway toward graduation and beyond.

“If we can grab them at kindergarten and start to give them the skills that they need in order to be successful students,” says Creeden, “we have the potential to prevent that student from being a high school dropout.”

“You’re always playing this game of catch up, except you never catch up.”

– Amy Creeden, principal and Race to the Top lead

Using the same reasoning as it did for its two-year kindergarten program, Middletown decided to end “social promotion,” so that students are not moved on to the next grade if they aren’t ready. The district estimates that before the initiative began, about 60 percent of students were moving on to the next grade without being proficient in fundamental skills.

Parents initially balked at the idea and some fought it, citing the stigma that comes with a student being held back. The district’s intent, however, is not to hold students back in the traditional sense.

“There’s research that’s been there for years that says to simply retain our children and put them right back in the same program that they failed the previous year is pointless,” says Gordon Dean, principal at Twin Towers Middle School.

Instead, Middletown created what it calls a “Mid-point” program, where students who are not academically ready for the next grade level receive a year of instruction targeted toward building the skills the need.

“If I know that you’re reading on a first-grade level, then that’s where I’m going to take you,” says Eileen Keith, a third-grade teacher who has been in the district for nearly 20 years. “Maybe your friend across from you is on a second-grade level, then I’m going to work with them on their level. Wherever their academic needs are, that’s what you teach them.”

Students may be in class with the same teacher and some of the same classmates as the previous year. This establishes some social continuity and deeper relationships with teachers, who work with students to set academic and personal goals. When students do catch up and move on to the new grade level, their new teachers are expected to help ease the transition by providing extra attention and instruction until the students feel comfortable.

The initiative is in place at elementary and middle schools in Middletown. Some studies suggest achievement gaps that exist beyond the third grade are difficult to close regardless of the intervention. Over time, the district hopes, it will identify student needs and help them develop skills earlier and earlier, so that the Mid-point program — and associated cost — is no longer necessary outside early elementary years.

“You become very attached. You take a personal interest,” says Keith. “It almost is a challenge: ‘You know what, I’m going to make you do better if it kills me.’”

“This is what education is going to look like. These kids are surrounded by technology, and it just helps foster learning for these students.”

– Kylie Mollicone, third grade teacher

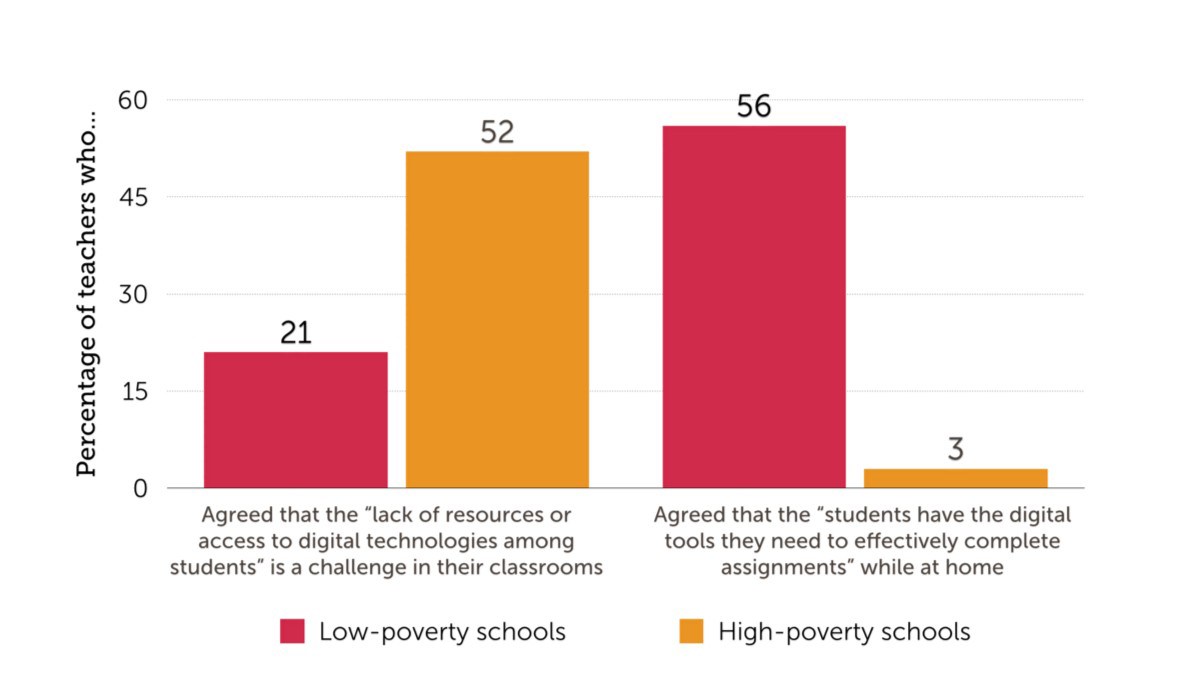

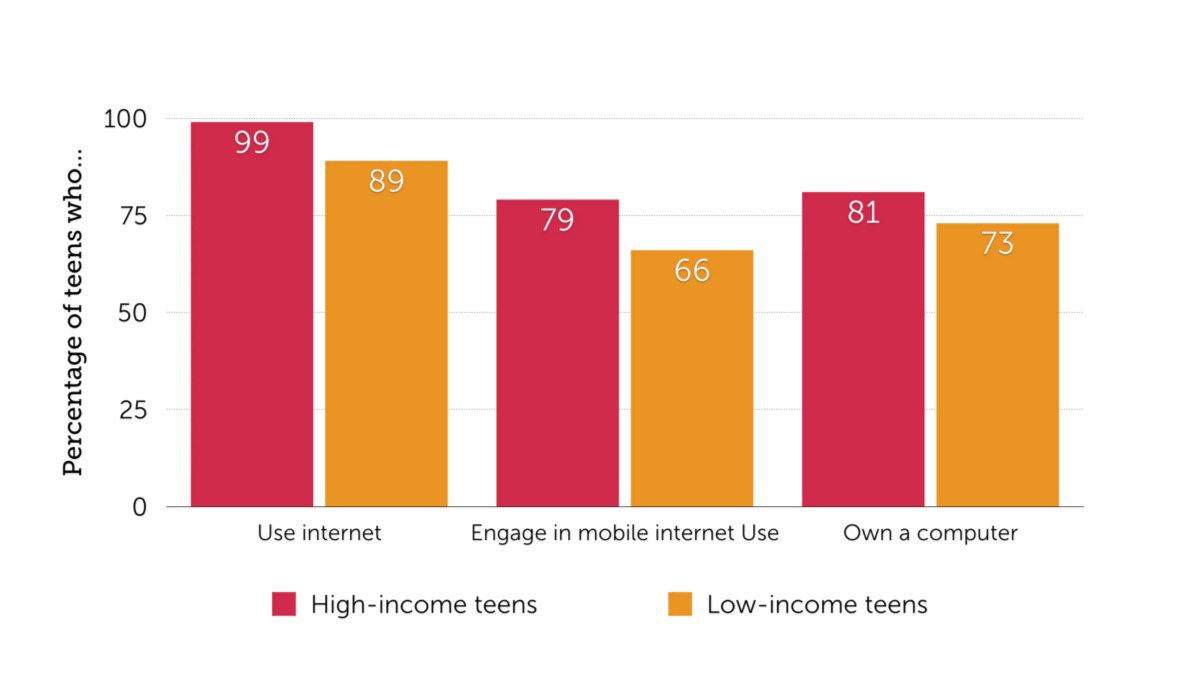

Studies show that low-income and minority students are less likely to use the Internet or own a computer. About 30 percent of households don’t have high-speed broadband, with a higher concentration of those households in minority and low-income communities, according to a brief by the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. Overall, there is a risk that a “digital learning gap” is forming on top of the achievement gap that already exists.

In 2013, as part of an effort to head off the digital learning gap, Middletown began to provide every student with a personal device and to equip teachers with the skills to personalize learning for every student.

By doing so, Middletown’s leaders believe its disadvantaged students will gain access to information and opportunities that many middle- and upper-class students may take for granted. But they also know a device alone is not enough. Del Moro, the Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum and Instruction, points out that using technology as an instructional tool lets students “really engage at their particular level. It helps the teachers differentiate the instruction to meet the child’s needs.”

“Technology clearly is not a silver bullet,” Eastwood, the superintendent, says. “As far as I’m concerned, the silver bullet in education is the teacher.”

Initially, K-8 teachers were asked if they wanted to opt in to blended learning environments, which mix online and face-to-face instruction. They showed some trepidation. Their job is challenging enough without having to learn a whole new approach, Eastwood and Creeden recall hearing.

That’s why Middletown is investing as much in professional learning for teachers as it is in devices and broadband. Teachers are supported by three “teachers on special assignment,” who stepped out of the classroom to provide full-time instructional technology support. Instead of elementary teachers covering literacy and math, they were freed up to specialize in one content area. A daily 30-minute intervention period was added for all elementary students.

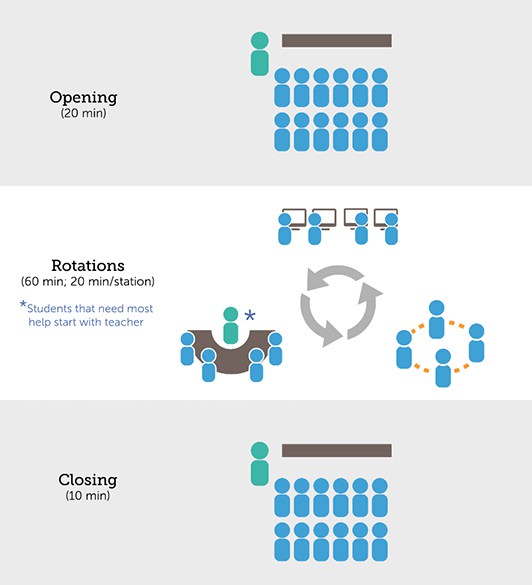

Below is a sample schedule for a 90-minute, 4th-grade class. The teacher assigns each student to a group and lesson based on her knowledge of that student’s strengths and weaknesses, determined in part by data provided through learning software. (Some teachers also have students assess their own mastery of skills.)

In this case, the group of lower-performing students start with the teacher so she can set them on a course for the rest of the class period. That group finishes the rotation with online learning, which is an opportunity to apply what they learned through the class period.

As more teachers opted in to blended learning classrooms, they reported being able to learn more about each student. They work more closely with students in small groups and when students are using the online curriculum, their progress is all captured for the teacher to review.

“The student will always need time with the teacher, because the teacher really is the master at the formula for learning,” Eastwood says. “All the data in the world is great, but it has to be pointed in the right direction. That’s what a teacher does.”

With all of the district’s work to tailor the educational experience to each individual student’s needs, it’s clear there is no sustainable paper-and-pencil version of it. It requires technology and it requires great teachers. Studies have shown that low-income students achieve greater gains than more affluent students in environments with one-to-one technology and direct instruction from teachers.

Last year, students in blended classrooms outperformed those in non-blended classrooms by 57 percent in reading and 26 percent in math, according to Education Elements, a consultancy that works with Middletown on its blended learning efforts.

At the start of the 2015–2016 school year, all K-8 math and ELA elementary school classrooms in Middletown used some form of blended learning as part of their instructional approach. The goal for this year is to continue to expand the program at the middle school and to begin phasing in flipped instructional models at the high school level.

Given the results from the two-year kindergarten and blended learning initiatives, plus the 30 percent graduation rate increase over the past decade, Middletown can point to many victories in its sweeping efforts to turn around the district.

District leaders know, however, that these results have to be sustained over time for their bold efforts to truly pay off. The Race to the Top grant lasts for five years. While much of Middletown’s progress predates the grant, many of its boldest and highest-impact initiatives are made possible by the grant.

There is hope that providing these resources to high-needs students now will make those same resources unnecessary later. The district also benefits from longevity in its leadership; Eastwood’s 12th year in Middletown comes at a time when the average superintendent tenure in the U.S. is three years.

But not all of Middletown’s success must be measurable. Teachers, parents, and district leaders believe these efforts will change students’ perceptions of what they can achieve and their own self-value, which will have its own sustaining effect on the community.

“If you try to elicit from students something that they should be mad or sad about because they come from homes of poverty, you won’t get it,” says Eastwood. “They see their lives ahead of them as being successful and getting to those same kinds of jobs and colleges as everybody else.”

Photography

: Duy Linh Tu

Contributions: Farhod Family

Special thanks: Amy Creeden, Gordon Dean, Ken Eastwood, Brandi Hundley, Eileen Keith, Celeste Miller, Karim Miller-Simmons, Kylie Mollicone, Raquel Parker, Holly Samuels, Gianna Samuels, Jason Tomasulo, Jason Tomassini