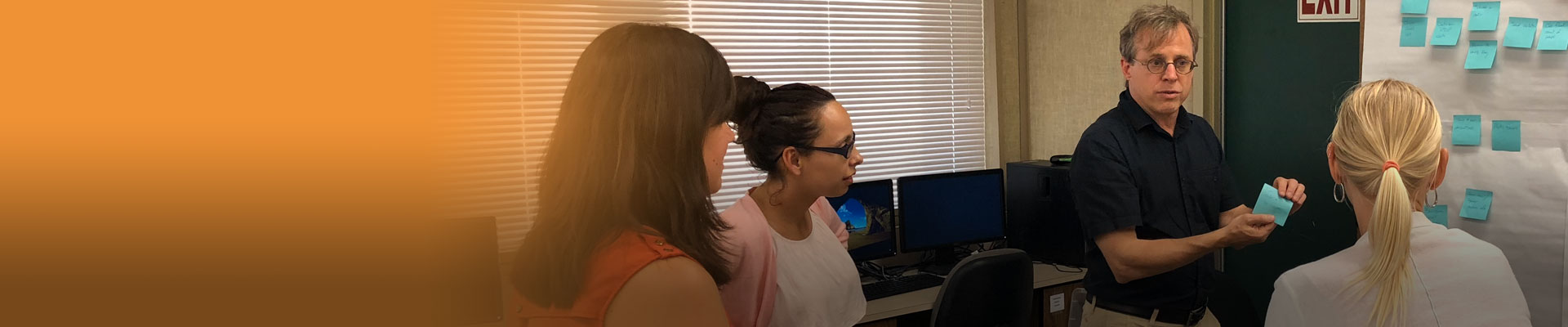

A main goal was to investigate how computational thinking (CT) skills could be meaningfully and equitably promoted across preschool and home. Our approach brought teachers, families, researchers, and media designers to (1) share their unique perspectives and insights, (2) brainstorm whether and which CT skills could be consequential for early learning, and (3) collaboratively develop (and test) hands-on activities and digital apps. Read more about our approach in our blog post.

Our work also involved investigating connections between CT and early math and science. As teachers, families, researchers, and media designers co-designed activities, they explored which connections emerged organically.

CT and Early Math  |

CT and Early Science  |

|---|---|

|

Most of the CT activities that emerged during co-design meetings relied on and/or provided children opportunities to practice and strengthen their |

Only a few of the CT activities that emerged during co-design involved science; activities that did, supported children’s engagement in science practices. |

|

Example/s Learning experiences designed to promote algorithms often involved visual spatial activities, as well as numeral recognition and counting. For example, children learned to give/read a sequence of directions for peers to navigate spaces. When working with loops they learned to create codes using numbers. When children decomposed problems and engaged in abstraction activities involving sorting, they often practiced counting and comparing quantities. For instance, children counted the number of subtasks they needed to complete when they decomposed problems and compared quantities in groups they had sorted. |

Example/s Learning experiences designed to promote abstraction (CT) often involved sorting objects based on observable characteristics as a way of highlighting necessary information (while ignoring irrelevant or unnecessary information). For example, children discussed how sorting food at the market can help customers easily find what they need or how sorting toys or blocks could help them build towers or ramps and pathways more efficiently. |

CT and Early Math  |

Most of the CT activities that emerged during co-design meetings relied on and/or provided children opportunities to practice and strengthen their |

|---|---|

CT and Early Science  |

Only a few of the CT activities that emerged during co-design involved science; activities that did, supported children’s engagement in science practices. |

CT and Early Math  |

Example/s Learning experiences designed to promote algorithms often involved visual spatial activities, as well as numeral recognition and counting. For example, children learned to give/read a sequence of directions for peers to navigate spaces. When working with loops they learned to create codes using numbers. When children decomposed problems and engaged in abstraction activities involving sorting, they often practiced counting and comparing quantities. For instance, children counted the number of subtasks they needed to complete when they decomposed problems and compared quantities in groups they had sorted. |

CT and Early Science  |

Example/s Learning experiences designed to promote abstraction (CT) often involved sorting objects based on observable characteristics as a way of highlighting necessary information (while ignoring irrelevant or unnecessary information). For example, children discussed how sorting food at the market can help customers easily find what they need or how sorting toys or blocks could help them build towers or ramps and pathways more efficiently. |