July 31, 2014 | By Digital Promise

Location: Meridian, ID

Location: Meridian, ID

Enrollment: 36,200 students

Superintendent: Linda Clark

Per-pupil funding: $4,500

Low Income: 30%

In school districts, strategic decisions that affect teachers – what textbooks to purchase, what classrooms look like, and what instructional approaches teachers should use – traditionally come from the top.

And recent advances in educational technology mean there are an unprecedented number of digital solutions for districts to choose from. But now teachers, the true end-users of these technologies, can seek out their own tools and resources with a simple click. School districts must now decide what to do with teachers’ newfound agency. Many are embracing it as a way to spur bottom-up innovation and ensure teachers can influence districts’ policies and strategies.

One district counting on its teachers to move schools forward is West Ada School District, formerly known as Joint School District No. 2, in Meridian, Idaho. With just over 36,000 students, West Ada is the largest school district in Idaho, but has among the lowest per-pupil funding level in the nation for a district of its size. These limited resources means the district must take advantage of the ideas and efforts of its teaching staff, says Superintendent Linda Clark.

“How to change classrooms has to come from teachers.” Superintendent Linda Clark

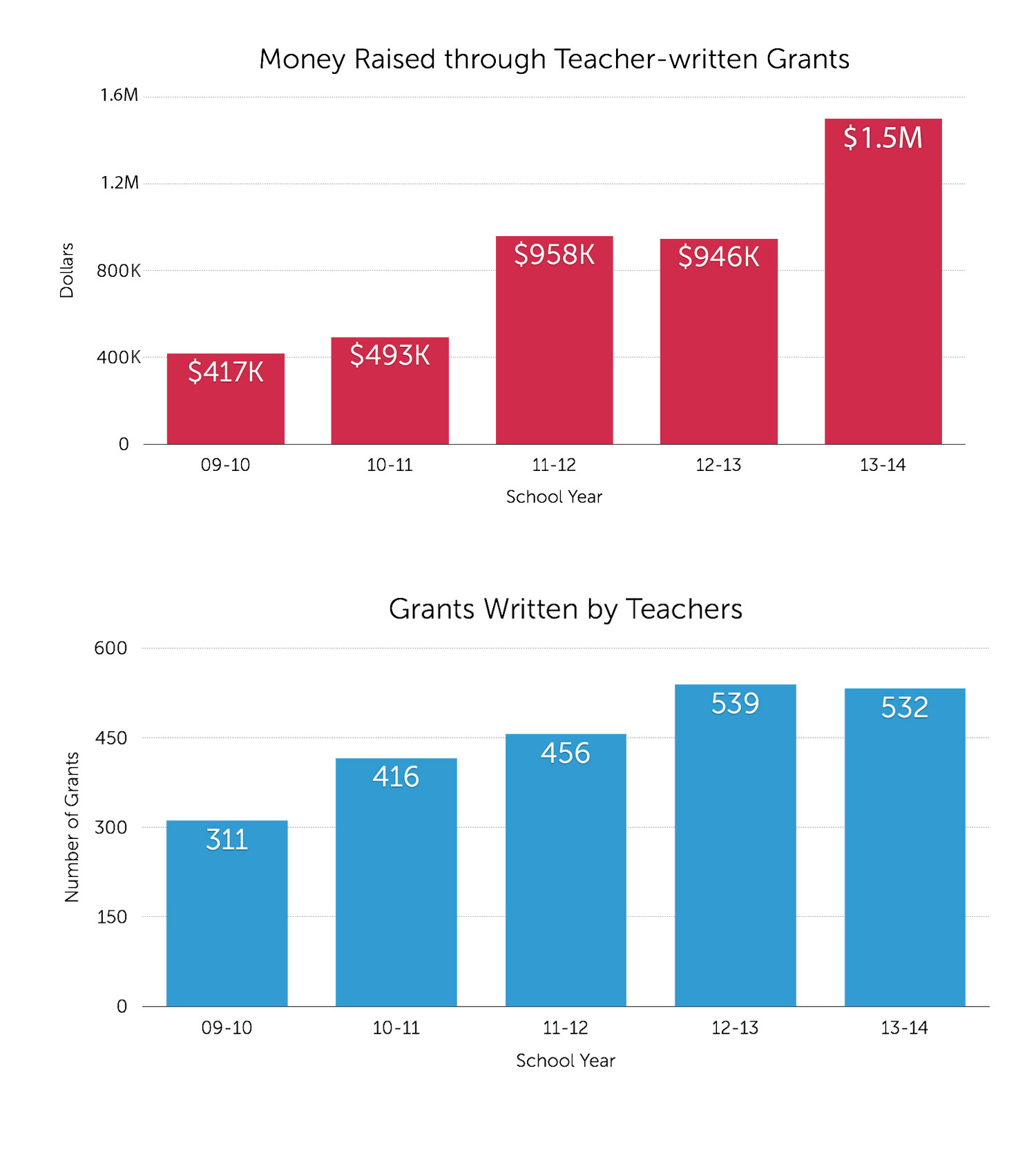

Encouraging teachers to incorporate technology into the classroom has motivated and empowered them to seek it out. Teachers at West Ada have raised more than $1.5 million for instructional technology by applying for local and national grants, and they continuously share their ideas, successes, and challenges through professional learning communities within the district.

Administrators now view their role as giving guidance on how to manage technological infrastructure, providing professional development, conducting internal research, and scaling teacher practices that make an impact for students. In 2012, the district tested this theory through an internal research study, which gave five teachers the ability to design 21st century classrooms around technology, and is now expanding those technology-rich classrooms and blended-learning models throughout its schools.

“How to change classrooms has to come from teachers,” she says.

“This is about engaging students, using the tools they know and use,” says Clark, a 35-year veteran at the district who has spent the past 10 years as superintendent. “We have to consider the fourth R – reality. Our job is to prepare students for the reality of life when they graduate and leave our classrooms, and technology will play an increasing role in that reality.”

But bucking tradition can be difficult. Ongoing challenges include ensuring quality teacher practice, balancing accountability with innovation, and managing the pace of adoption across hundreds of classrooms. The most important question West Ada must answer: How to sustain all of this innovation?

is the largest school district in Idaho, encompassing six municipalities in Ada County, including some of Boise. Set in the Treasure Valley of the Boise foothills, the district is economically and demographically dispersed, with pockets of wealthy subdivisions, rural farmland, and low-income neighborhoods; 30 percent of students are eligible for free and reduced priced meals, though those populations tend to be concentrated in certain areas. Due to minimal funding, the district of 36,225 students and 384 square miles employs only 115 central office staff, performing duties ranging from managing information technology for its 53 schools to creating and aligning curriculum to organizing and serving lunches to the entire student body each day.

Despite these limitations, West Ada is quick to adapt. Using a local plant facilities levy, it was one of the first districts in the region to use computers in the classroom, the first large district in the country to offer computerized assessments, and has worked to stay ahead of the increasing demand for broadband in the district.

Even as an early adopter, West Ada still only had islands of effective technology use as recently as 2010. A handful of teachers had received funds from various sources for mobile technology and the results were positive. Based on the interest and preliminary work with tablets by teachers at Star Elementary School, the district started a pilot program using a rotational blended-learning model and tablets in grades 4-5. Other schools in the district were also testing various devices in the classroom.

Examples from these schools led the district to consider how it could provide a relevant education to all of its students, instilling problem-solving, critical thinking, and collaboration skills through modern communication and productivity tools. Other districts had implemented one-to-one technology across its classrooms, but that approach was too costly and unwieldy given West Ada’s budgetary limitations.

of its students, instilling problem-solving, critical thinking, and collaboration skills through modern communication and productivity tools. Other districts had implemented one-to-one technology across its classrooms, but that approach was too costly and unwieldy given West Ada’s budgetary limitations.

“I recognized I couldn’t do another top-down initiative,” Clark says.

So Clark focused on the success of teachers who jumped at the opportunity to use new instructional tools. How could the experiences of that exemplary minority spread to a majority of teachers, many of whom who craved new classroom environments but did not know how to get there?

“Teachers and principals are eager to use these tools,” Clark says. “They know it’s a part of students’ everyday life. They want instruction to reflect that.”

West Ada set out to support teachers in pursuing instructional technology, but knew it had to do so without a significant influx of operating funds – in fact, the district was rapidly losing state-level funding at the time.

Several proactive teachers in the district had already written grants to acquire their own classroom technology. Beyond the fundraising component, the district recognized this behavior as displays of innovation and leadership. The district decided that formalizing and bolstering its teacher grant-writing efforts could not only support its existing teacher-leaders, but create new ones.

In order to accomplish these goals, the district hired a grants and gifts facilitator, whose role is a mix of resource management and instructional technology support. Bernadette Sexton, a former teacher and education technology specialist, now holds that position. Sexton helps teachers identify their hardware and digital curricula needs in the classroom and pursue potential funding sources aimed at digital integration. She also maintains a website with tips and resources for writing grants, and curates local and national grant opportunities for a regular email newsletter distributed to teachers through the district.

If you give a teacher the ability to go out and get the instructional tools they want, they really take charge and do something with it,” Sexton says. “Rather than somebody giving them iPads and saying, ‘Do this with the equipment,’ if they took the time to earn it on their own, they will take the time to use it effectively.”

Recent research from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation backs up this idea. In a survey of teachers’ views on digital learning tools, teachers were 30 percent more likely to deem a tool effective if it was something they chose on their own.

In 2010-2011, the year before West Ada ramped up fundraising efforts, district teachers wrote 416 grants, raising an impressive $493,000 from external sources. During the 2013-2014 school year, those figures increased to 532 teachers who collectively raised $1.5 million for hardware, software, and other classroom tools.

Administrators at West Ada School District understand that teachers writing individual grants is not a sustainable districtwide solution to technology implementation. The district views the awarded projects as seeds of innovation that may be worthy of additional investment. To support ideas that work, the district offers internal innovation grants. The first three rounds of grants, which began in 2011 and used dollars from the federal E-Rate program, were open to any teacher in the district. The fourth round was considered a scale-up grant, available only to previous recipients that had demonstrated promise.

Administrators at West Ada School District understand that teachers writing individual grants is not a sustainable districtwide solution to technology implementation. The district views the awarded projects as seeds of innovation that may be worthy of additional investment. To support ideas that work, the district offers internal innovation grants. The first three rounds of grants, which began in 2011 and used dollars from the federal E-Rate program, were open to any teacher in the district. The fourth round was considered a scale-up grant, available only to previous recipients that had demonstrated promise.

Projects ranged from the use of single apps to a set of student devices to support for entire multimedia lesson plans. With this approach, the district ensured that the best ideas bubbling up from the classroom had the necessary resources to be fully realized.

For the most recent round of internal grants, West Ada wanted to engage teachers who had not joined in the district’s innovation efforts; only those who had not previously received a grant could apply. After promoting the grant program and its participants, more than 80 teachers submitted their first innovation grant application and were awarded a total of $52,000. West Ada used state technology funds, rather than federal E-Rate money, for the most recent rounds of grants. With more than $84,000 in grant requests funded in the latest round, district officials were encouraged, seeing it as a strong indicator that teachers were engaged in the bottom-up digital conversion.

The district also participates in Teacher Wallets, a national initiative called that provides educators with discretionary funds to make their own budget and purchasing decisions about instructional technologies for their classrooms.

Part of what drives teachers to participate is seeing the success of their peers, which West Ada makes a point to highlight. At the district’s annual Tech Expo, teachers can demonstrate instructional technology approaches, show off students’ work, and demonstrate new tools. In order to receive an internal grant for technology, teachers must attend the expo. The event typically draws about 900 teachers, many from neighboring districts, as well as local and national technology vendors. Based on the success of the annual event, the district now holds smaller events throughout the year for teachers to showcase and talk about their work.

A key to driving these grassroots efforts is identifying leaders within West Ada’s teaching ranks. One such leader is Melissa Slocum, a first-grade teacher who used to work in the technology sector.

In 2012, Slocum applied for a grant to purchase a digital publishing tool so her students could share their work with her and their classmates online. She did not receive the grant, but remained persistent and began to envision a collaborative environment where she was no longer the center of the class but a facilitator. By using mobile technology like tablets, young students would learn in an environment familiar to them, with flexibility in time and space. To achieve this Slocum realized she needed more than just a digital publishing tool; she needed an entire suite of hardware and apps, as well as new classroom furniture.

Working with Sexton, the grants facilitator, Slocum drafted a model of her ideal classroom environment and the activities students would be able to do, and pitched it to the district. Coincidentally, the district was planning to open a new school and considering innovative models to use.

Clark saw an opportunity to not only support Slocum’s vision, but test it as an approach the district could use in its new school and potentially beyond. Through a partnership with Digital Promise and the Verizon Foundation, the district launched a pilot initiative and research study called 21st Century Classrooms to see what would happen if teachers were permitted to design their own classrooms and curricula around technology.

Five elementary teachers were selected for the project and Reed Stevens of Northwestern University’s School of Education and Social Policy studied teacher behavior and decision-making. As the project evolves, West Ada is learning from the experiences of its five teachers and shaping how it expands 21st-century classrooms districtwide.

Eian Harm, the district’s research coordinator and facilitator of innovative projects, says, “We want to have the models in place for when we are capable of fully scaling.”

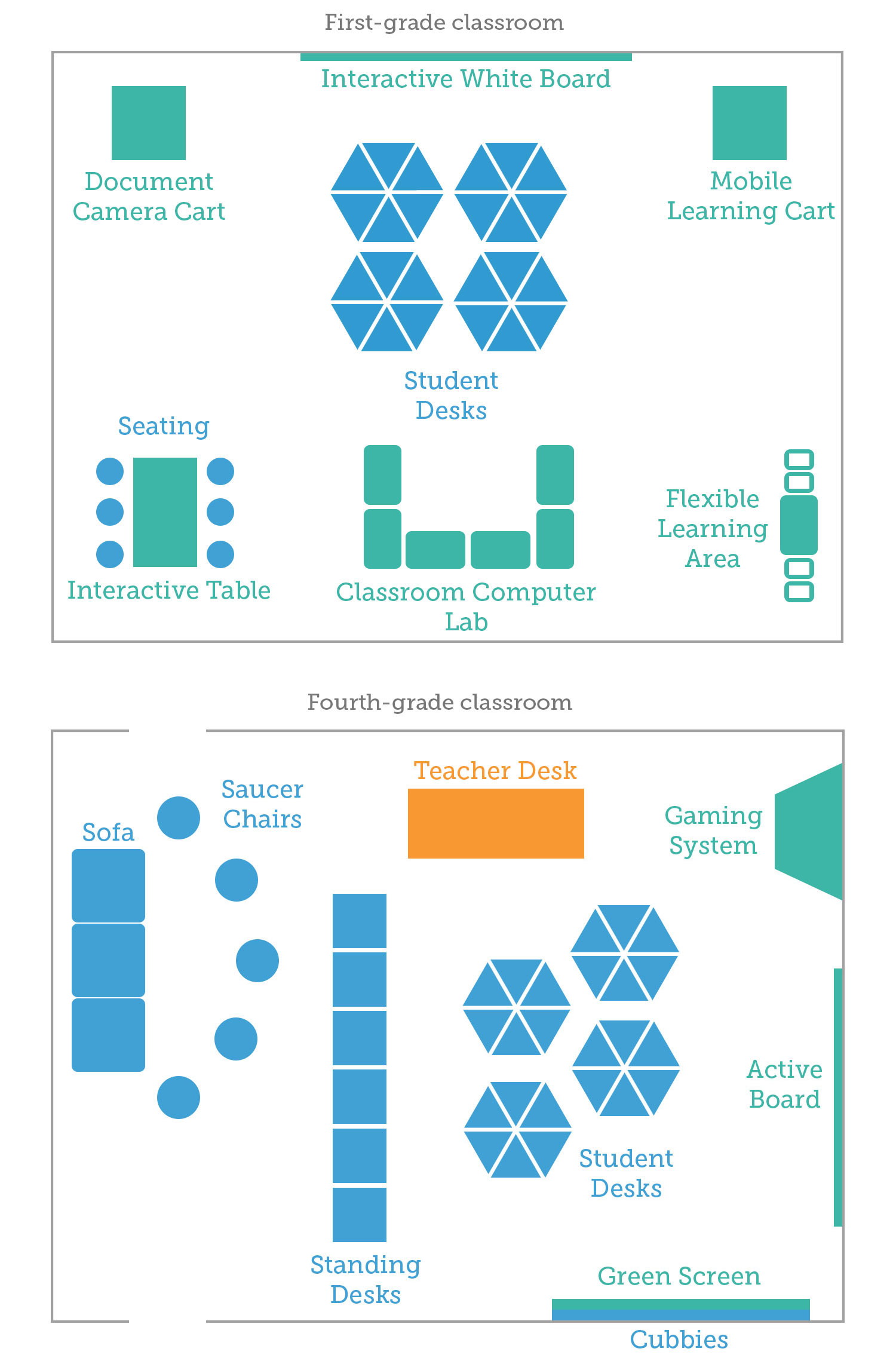

For the 21st Century Classrooms project, West Ada sought teachers with a vision and enthusiasm for blended learning. Each classroom received five laptops, five tablets, and five iPods, as well as an interactive whiteboard and interactive table.

“With different kinds of tools in the classrooms, instead of just one, a teacher can purposefully select the tool that works best for each activity,” Clark says.

The devices were preselected by the district for easier management and integration into broadband networks, and the district closely observed how devices were used in order to help inform future purchasing decisions. Each teacher was free to design the classroom as he or she wanted, using the devices and selecting furniture purchased with funds provided through the project.

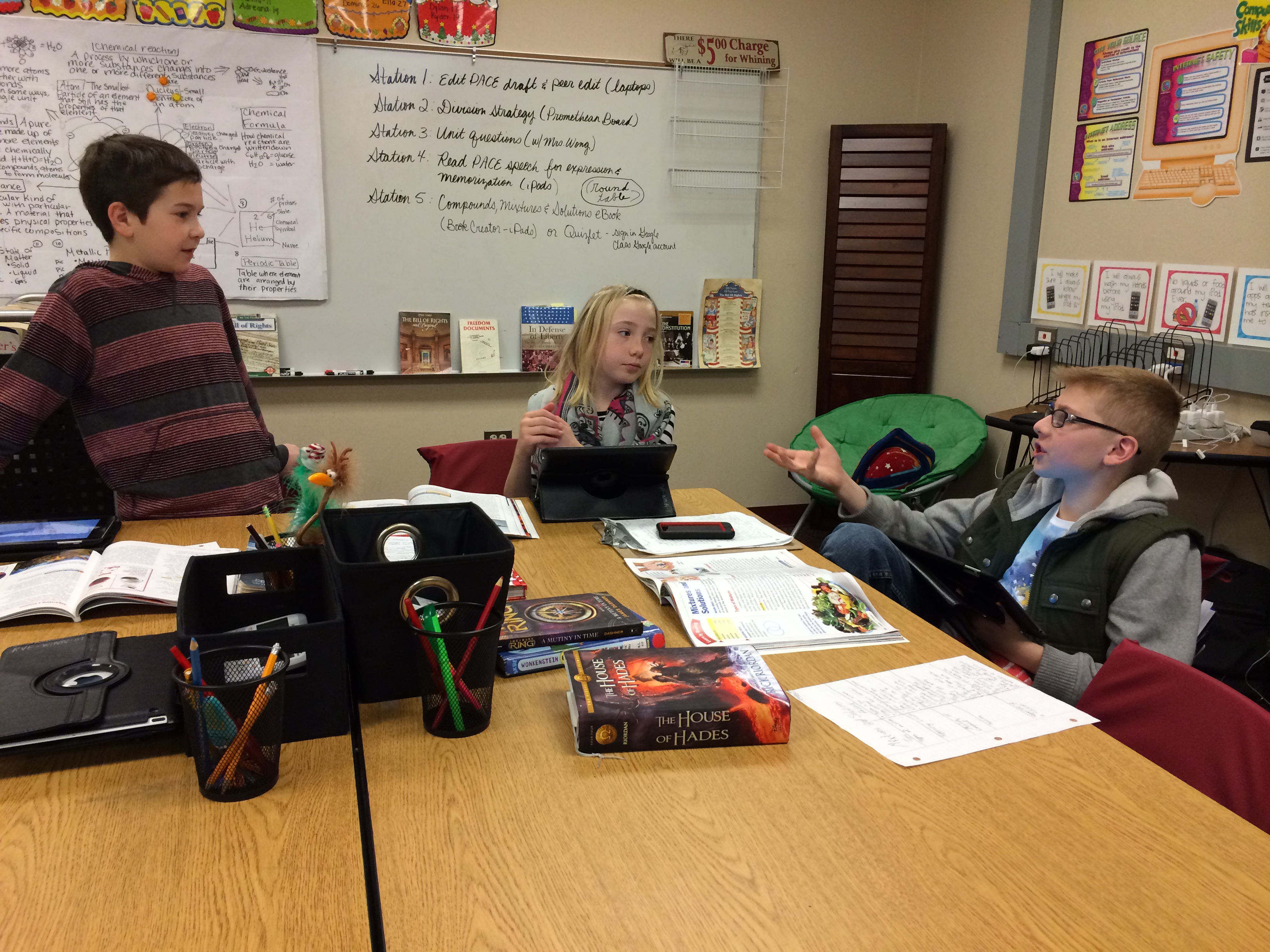

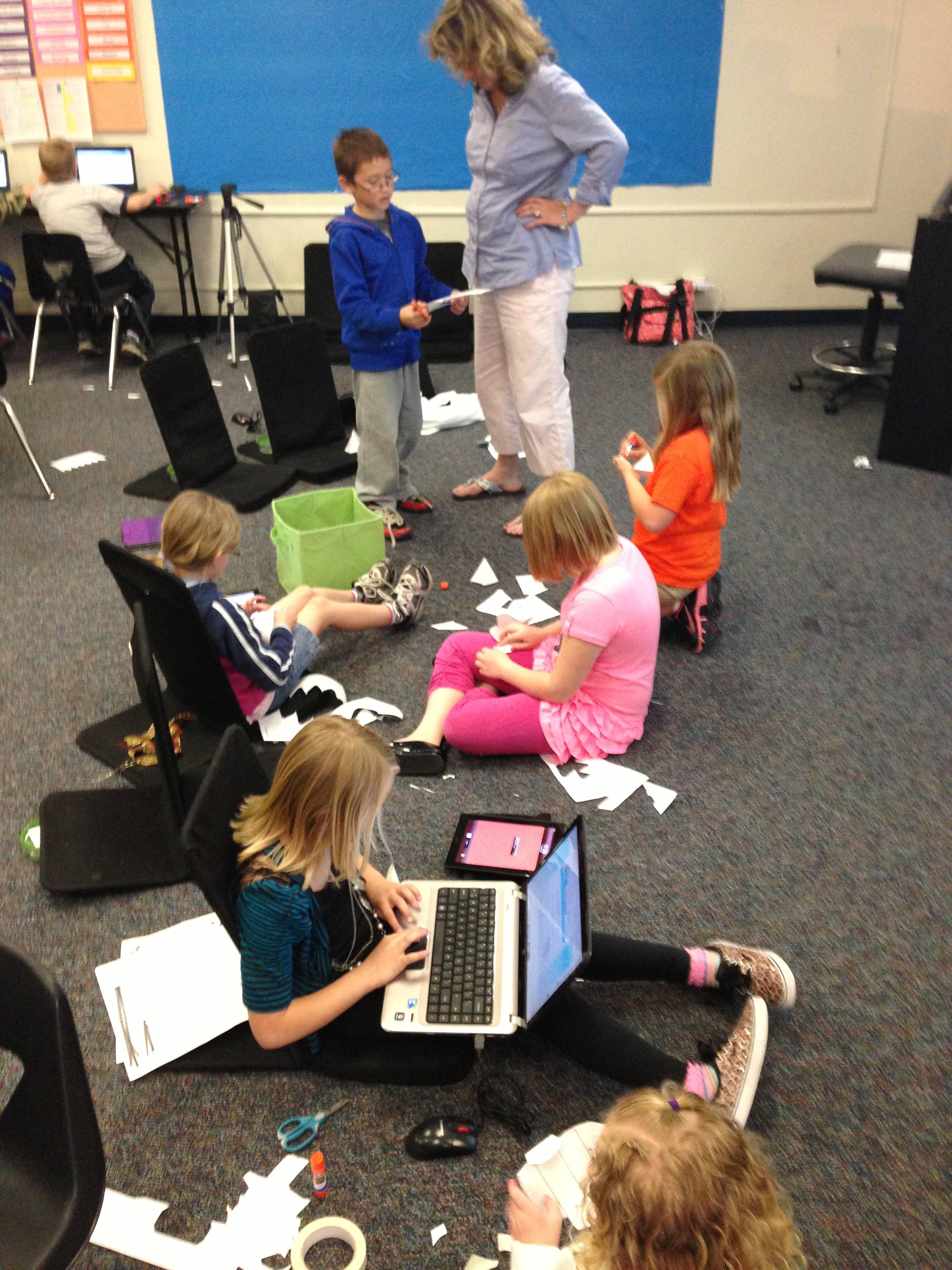

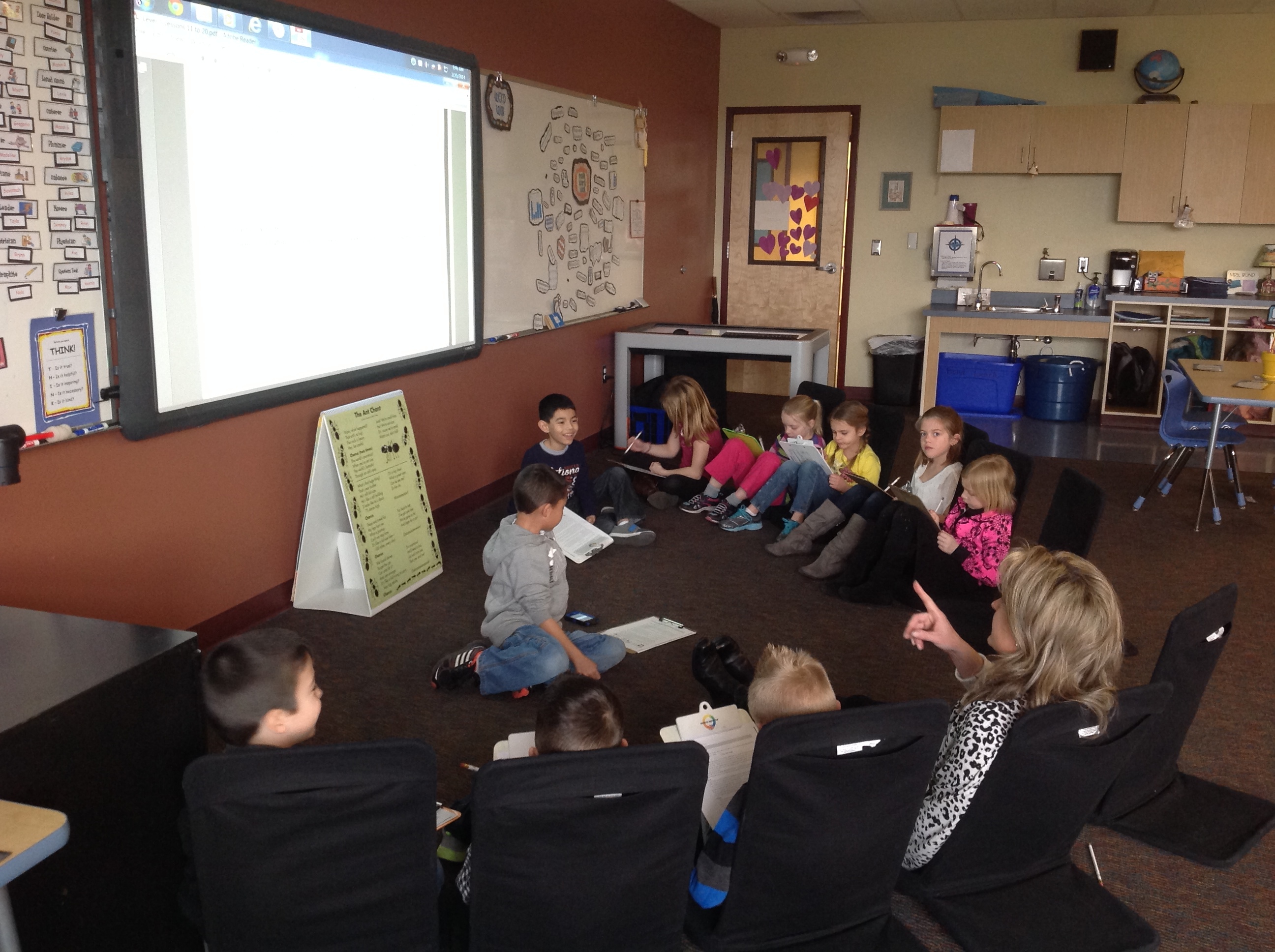

Across the classrooms, design choices were intended to spur creativity among students and decentralize the role of the teacher, with technology a tool to spark student ownership of learning. Teachers chose items like standing desks, couches, floor chairs, and green screen areas for video recording, all features with student learning habits in mind. It is common to walk into a 21st-Century Classroom at West Ada and see empty desks, with students working collaboratively in groups scattered throughout the space.

Teachers use a blended learning model in which students rotate through analog and technology-assisted activities. Some activities are organized and led by students, others are led by teachers; some involve listening and responding, some involve active production, and some emphasize sight, hearing, touch, or physical action. Even though there is an emphasis on digital tools, ample time is for hands-on work away from screens.

Teachers use a blended learning model in which students rotate through analog and technology-assisted activities. Some activities are organized and led by students, others are led by teachers; some involve listening and responding, some involve active production, and some emphasize sight, hearing, touch, or physical action. Even though there is an emphasis on digital tools, ample time is for hands-on work away from screens.

Within this approach, teachers can take big leaps in handing ownership of learning over to students. In observations over a 14-month period, it was common to see teachers traveling from group to group, checking in with students and offering help if needed, and acting more as facilitator and troubleshooter than as a direct instructor.

One second-grade teacher meets individually with each student for 15 minutes per day, usually in the hallway during class, to set and review his or her individual goals. The goals range from measurable and academic, like completing a certain number of assignments, to developmental and social, like becoming a better problem solver.

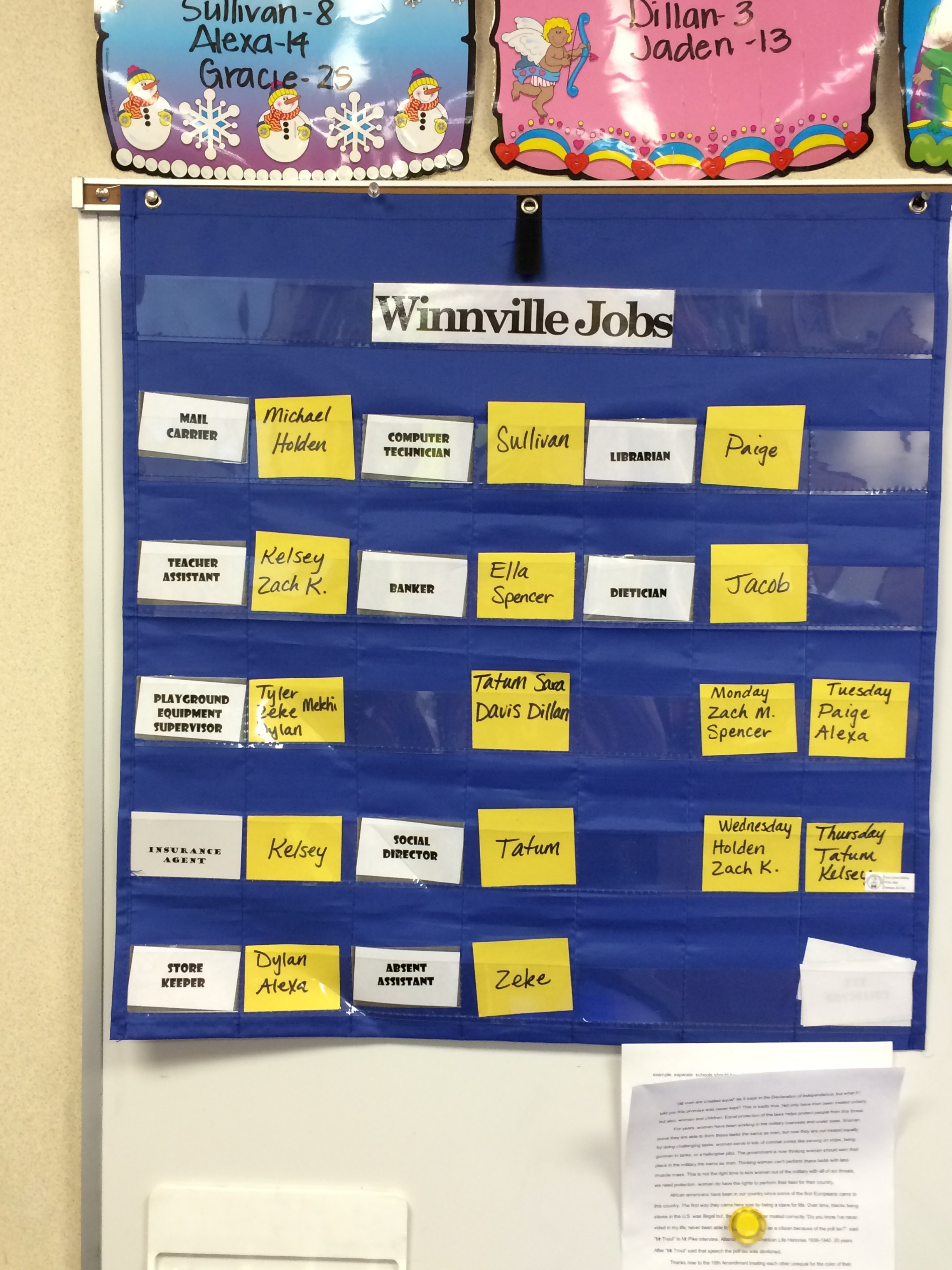

Another teacher posts a chart in the classroom with each student’s individual rotation for the day. She simply signals when a new rotation must be made and students know what to do and where to go on their own.

Another teacher posts a chart in the classroom with each student’s individual rotation for the day. She simply signals when a new rotation must be made and students know what to do and where to go on their own.

A few of the teachers incorporated the concept of creating a class economy, where students apply for and are assigned jobs such as banker, librarian, or, within group work, project manager. Students can earn privileges for doing their jobs well.

In these classrooms, it is striking to see how students are propelled by their own inertia, rather than by the typical, constant reminders from a teacher.

“It’s hard to stop them and say they are done with one thing and it’s time to go on to the next,” one teacher says.

For all teachers in West Ada, this approach required a significant amount of adjustment. Some teachers were more comfortable handing over control than others and moving from a whole-group approach to small group rotations. The district acknowledges it can’t expect all teachers to progress at the same pace.

“Like any other invocation, you have early innovators and others who come along more slowly,” Clark says.

The five initial teachers participating in the 21st Century Classrooms project are viewed as those early innovators, and are expected to share what they learn. Teachers involved in the project meet once per month and participate in an Edmodo community to discuss challenges and successes, and to trade tips on effective lessons and pedagogy. The goal is not to create a group of identical teachers, but encourage as many as possible to innovate.

“Not everything you do is going to work,” Clark says. “It’s an important lesson to have something not work and use that experience to learn how to do it better next time.”

Using a combination of state technology funds, the local plant facilities levy and federal funds, West Ada expanded its 21st Century Classrooms model to three full schools and more than 80 classrooms in other schools. Two additional schools will be fully equipped in all classrooms when school starts this fall. With the expansion, there are important modifications based on research from the pilot classrooms.

For instance, because of its surprising popularity this year, classrooms will feature a green screen, which allows students to mesh live and recorded video into the same projects. Each teacher will be encouraged to use standing desks and open floor space instead of just rows of desks. Students did not use the interactive table to its fullest potential so those were not included in the additional classrooms. The district is encouraging all elementary teachers equipped with technology to adopt a blended rotational model.

The district is identifying teacher-leaders who can help prepare and motivate peers to make this shift. One is Heather Bond, a second-grade teacher who moved from Lake Hazel Elementary School to the newly-opened Willow Creek Elementary School for the 2013-2014 school year. Bond has embraced blended learning and the hope is by placing her in a new school that is adopting 21st-century classroom methods, her skills and enthusiasm will spread throughout the building.

As part of the school’s professional learning community, she leads regular meetings and conducts classroom observations.

“The other teachers here are more than just my neighbors,” she says. “I want to collaborate and help them get better.”

At the district level, there are efforts to better understand the effects of these new instructional models. Harm, the research coordinator and facilitator of innovative projects, is studying student engagement, student collaboration, problem-solving, and teacher behavior in classrooms with the tech-integrated model vs. those without.

Harm uses an adapted version of the AIMS survey instrument created by Roehrig and Christensen (2010), researchers from Florida State University’s College of Education, to measure student perception of their classrooms at different intervals during the year. He is also incorporating a “teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction” scale to obtain insight into how teachers manage classrooms, deliver instruction for students, and view their workload — all characteristics affected by technology

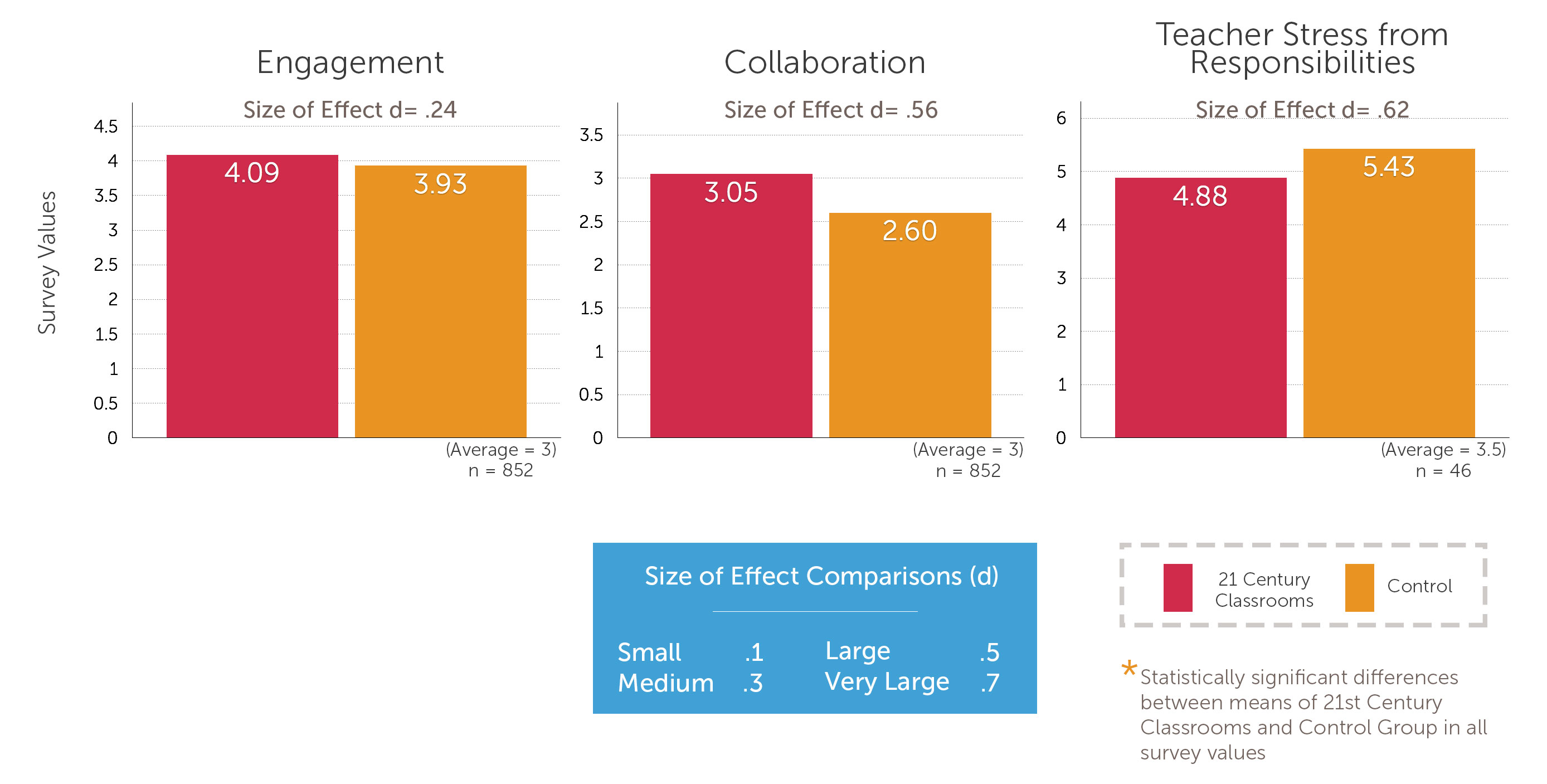

In February 2014, he found that students in the tech-integrated classrooms reported a small to medium increase in engagement levels higher than those in regular classrooms. Students in 21st-century classrooms reported the amount of collaboration that occurs was a large amount higher than those in regular classrooms. Among teachers surveyed, those in regular classrooms reported a stress level a large amount higher than those in 21st-Century Classrooms (see figures below).

Technology specifically is not what drives these results, but the district believes it is a sign that giving teachers more control over their classroom, and teachers in turn giving students more ownership of learning, can lead to higher satisfaction and thus better student achievement. West Ada cites data from Gallup’s recent poll of 600,000 students nationwide that indicates a one percent increase in reported student engagement can correlate with a 6-8 point increase in achievement.

Technology specifically is not what drives these results, but the district believes it is a sign that giving teachers more control over their classroom, and teachers in turn giving students more ownership of learning, can lead to higher satisfaction and thus better student achievement. West Ada cites data from Gallup’s recent poll of 600,000 students nationwide that indicates a one percent increase in reported student engagement can correlate with a 6-8 point increase in achievement.

West Ada is also conscious not to create a “technology vs. no technology” perception in the district and to focus on a shared set of instructional goals and student outcomes, rather than hardware or software. Classrooms designated as “21st century” are not the only ones in the district using technology; all schools and teachers can use it as their own discretion and within the district’s guidelines.

Those guidelines are crucial. In letting teachers seek their own technology, West Ada risks creating a Wild West of devices across each building and across the district. The more varied the tools, the more difficult the devices – and the apps and software that come with them – are to manage and to procure.

Educators are not permitted to use devices with different operating systems in the same building. All grants must first go through the district’s curriculum director. And the district’s technology staff recommends what hardware, operating systems, and software to seek, for easier integration into the existing network.

Job description for Eian Harm, the research coordinator and facilitator of innovative projects at West Ada.

This is a two-way conversation. Many of the district’s guidelines and recommendations are influenced by trends and preferences among its teachers.

“As district leaders we can curate the choices. You can’t give everyone carte blanche,” Clark says. “As you scale something, you have to begin to standardize it to have long-term sustainability.”

West Ada realizes that simply allowing teachers to seek their own innovative classroom environments does not necessarily correlate with improved student achievement, or certainly scalable and sustainable innovation across the district. If there are three phases to this effort – implementation at the classroom level, sustainability at the classroom level, and expansion to other classrooms – the district is certainly in the early phases.

One ongoing consideration identified by teachers is the increasing focus on assessment, and the shift in expectations brought on by new academic standards. As students progress through grade levels, curricular standards become more specific and testing becomes both more frequent and consequential.

“Testing won’t measure at all what those classrooms have done for those kids,” says Sexton.

Even when systemic change occurs, it is difficult to gauge whether it is achieving deeper levels of student learning and engagement. The results of Harm’s research are promising but limited in sample size and, as Sexton points out, standardized metrics are not always reliable.

In framing its pedagogical approach, the district uses the SAMR model, developed by Dr. Ruben Puentedora, which offers a continuum by which to measure the use of instructional technology. West Ada acknowledges most of its teachers are still exhibiting substitution, using technology to replicate analog activities. West Ada’s goal and challenge is to move enough teachers to the redefinition stage and to provide others with tangible models of effective digitally assisted pedagogy.

There is also the challenge of providing a consistent learning experience for students. Because blended learning is not used in every school, some students transition from highly collaborative, engaging environments to more traditional ones. Teachers may not see the value in teaching significantly differently if it is not consistent for students over the long term.

There is also the challenge of providing a consistent learning experience for students. Because blended learning is not used in every school, some students transition from highly collaborative, engaging environments to more traditional ones. Teachers may not see the value in teaching significantly differently if it is not consistent for students over the long term.

The balance between spurring innovation and managing it is constant for West Ada. Overall, the district believes a bottom-up approach is sustainable. When teachers see proactive peers pursuing the classroom tools they want, it’s more of a motivating factor than any plan prescribed by the district. That itself is a mechanism for scale.

And the district believes its role is to meet the bottom-up efforts from its teachers with top-down leadership from its administrators, creating a collaborative environment needed to truly sustain innovation.

“We are so used to the need to maximize everything we have that we think differently,” Clark says. “You’ll never hear when an idea is put out all the reasons that idea won’t work. You’ll hear discussion about what it takes to the make the idea a reality.”

Text:

Digital Promise

Reed Stevens (Northwestern University School of Education & Social Policy)Video:

Courtesy of Pearson Research & Innovation NetworkPhotography:

Digital Promise

Courtesy of Northwestern University School of Education & Social PolicyGraphics:

Digital Promise

By AJ Foster and Babe Liberman

By Josh Weisgrau and Teresa Solorzano