Change is hard! In my experience, I’ve noticed that teachers are more likely to make positive changes when they get to decide when and how to change.

I used to make changes in my classroom based on intuition – I just know what my students need – but found that intuition alone wasn’t enough to truly spark student learning. My gut might tell me what my students need, but there’s more to demonstrating why, for example, my 7th graders are more proficient writers when they use technology to publish their work.

That quest to prove the effectiveness of my own practice started my interest in finding “research-based” teaching practices. At first, I was skeptical about research. Just because something is research-based doesn’t necessarily mean it’s relevant or valid for my classroom. I read about action research, which is a type of research teachers can do themselves. It is intended to be used right away to solve an immediate problem. I wanted to try it myself and see what I could learn.

My first opportunity to try action research actually came not when teaching students, but when teaching teachers. I led an online professional development class in my district on embedding content area literacy. The feedback from teachers in the class was generally positive, but I wanted to know why the course had really been successful for them.

I created a simple survey, asking teachers what aspects of the course had been most effective. I learned that teachers who learn online still want a community within a virtual classroom. Teachers are reflective of our classroom learners, and need instruction differentiated to their needs. Their learning styles require video, visual text, and a variety of opportunities to show how they know what they are learning.

I used this feedback to make changes when I taught the same course again. This is action research!

I was so excited that I wanted other teachers to see how this process could impact their own teaching. I wanted teachers to get excited about change, rather than dread it. Most importantly, I wanted to start a conversation about keeping a growth mindset in education.

As a result, I offered a course called Action Research for the Real World to teachers of all grade levels and content areas, in a blended format (both online and face-to-face elements). I wanted to find out if teachers conducting their own research could develop a growth mindset and shift the way they notice events, solve problems, or ask questions in their own classrooms.

Carol Dweck, who I call the “queen of mindset,” says the view we adopt for ourselves profoundly affects the way we lead our lives, so we can assume that our mindset as educators will naturally impact the minds of our students. Some learners see their world as “fixed,” and believe they were born with all the skills and characteristics they will ever have (Dweck, 2012). Fixed mindset learners don’t believe they can change their circumstances, and often avoid failure by not taking risks. On the other hand, learners with a “growth” mindset see failure as a way to learn.

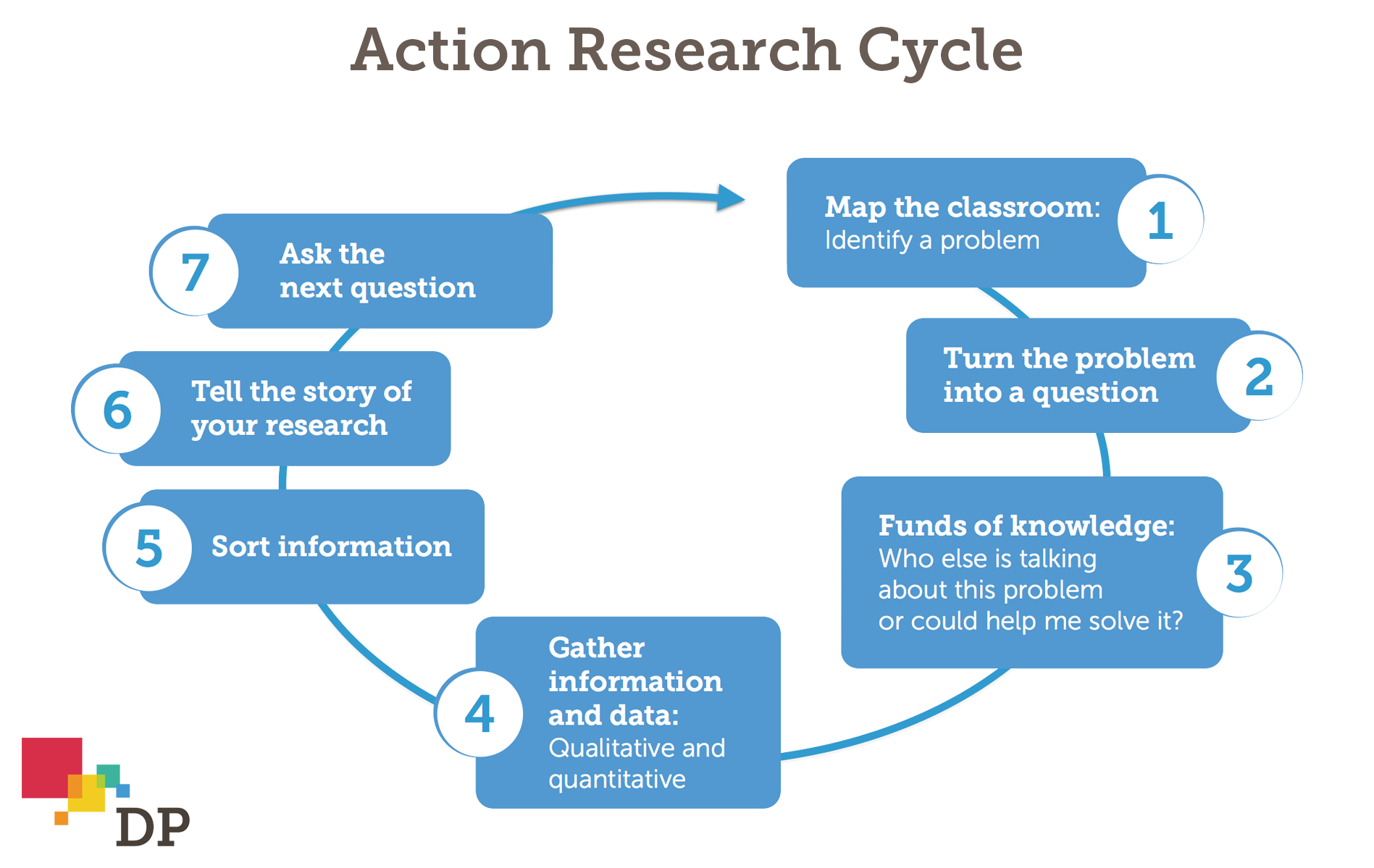

Here are seven steps that, in my experience, help teachers conduct action research, while developing a growth mindset along the way.

For our first face-to-face class, we mapped our classrooms to identify problems in our teaching space or processes. We asked: What is working? Who is learning? Is anyone left out? Where are the barriers to learning? We realized that although it makes us uncomfortable, when we ask hard questions, we open opportunities to find the answer.

In Step Two, teachers wrote questions they wanted to answer about their classrooms, such as:

As isolated educators, we often forget how other people and places help inform our thinking and fund our knowledge base. For example, when teachers were asked to identify thinking partners and start building a “fund of knowledge,” they were surprised to find unexpected resources in their spouses, neighbors, parents, or friends. We also looked for other researchers thinking about similar problems, and teachers read excerpts of research already conducted on their topic in content area journals or websites like Edutopia.

The next step involved gathering data from our classrooms to answer our questions. During this process, teachers realized that the weight placed on test data was so heavy that they often neglected information from more informal sources like journals, timetables, discussion responses, and observation.

Some teachers used formative or summative test data, but the most popular tool of inquiry was an informal survey. Simple questionnaires – from picture surveys with kindergarteners, to online Google forms for high school students – gave them valuable insight they had overlooked.

Teachers then sorted their data, looking for patterns that might answer their question. While a few teachers felt the data validated their hunches, many were left with more questions. One teacher’s survey, for example, revealed that students preferred a writing center, rather than her assumption that they preferred reading a book of their choice. Another teacher found that classroom technology motivated learning, but found that not all students had equal access. Teacher research leads to answers, even if the answers aren’t expected!

Our last task was to look at what our research was telling us. How could we begin to make sense of the information we gathered, and explain it? Because it was based on their own practice, the teachers’ findings led to immediate changes. One teacher said: “I see now how I can evaluate the effectiveness of my efforts in the classroom.” Another said: “I can’t believe I haven’t used these methods to solve problems earlier!”

We realized together that action research exists with a bit of ambiguity, and that when the answer isn’t clear, that just means we’ve identified another problem to solve, or need to refine our questions. This realization jump-starts the process over again with:

Action research is an ongoing cycle.

Overall, teachers were surprised to learn they like doing research, and felt that action research opened their minds. “I was surprised by some things that I learned that contradicted what I thought I knew,” said one teacher. “I was looking for validation, but didn’t always get it.”

Teachers who ask questions become open to change; they seek change as a catalyst to improve and validate teaching choices. Action research prompts us to ask the next question, ensuring that we grow.

Reference:

Dweck, C. (2012). Mindset. London: Robinson.