We hear a lot about the need for students to “learn at their own pace.” That instead of sitting in rows of desks with a teacher delivering the same information to everyone, students should be able to develop skills and explore knowledge whenever and wherever is best for them.

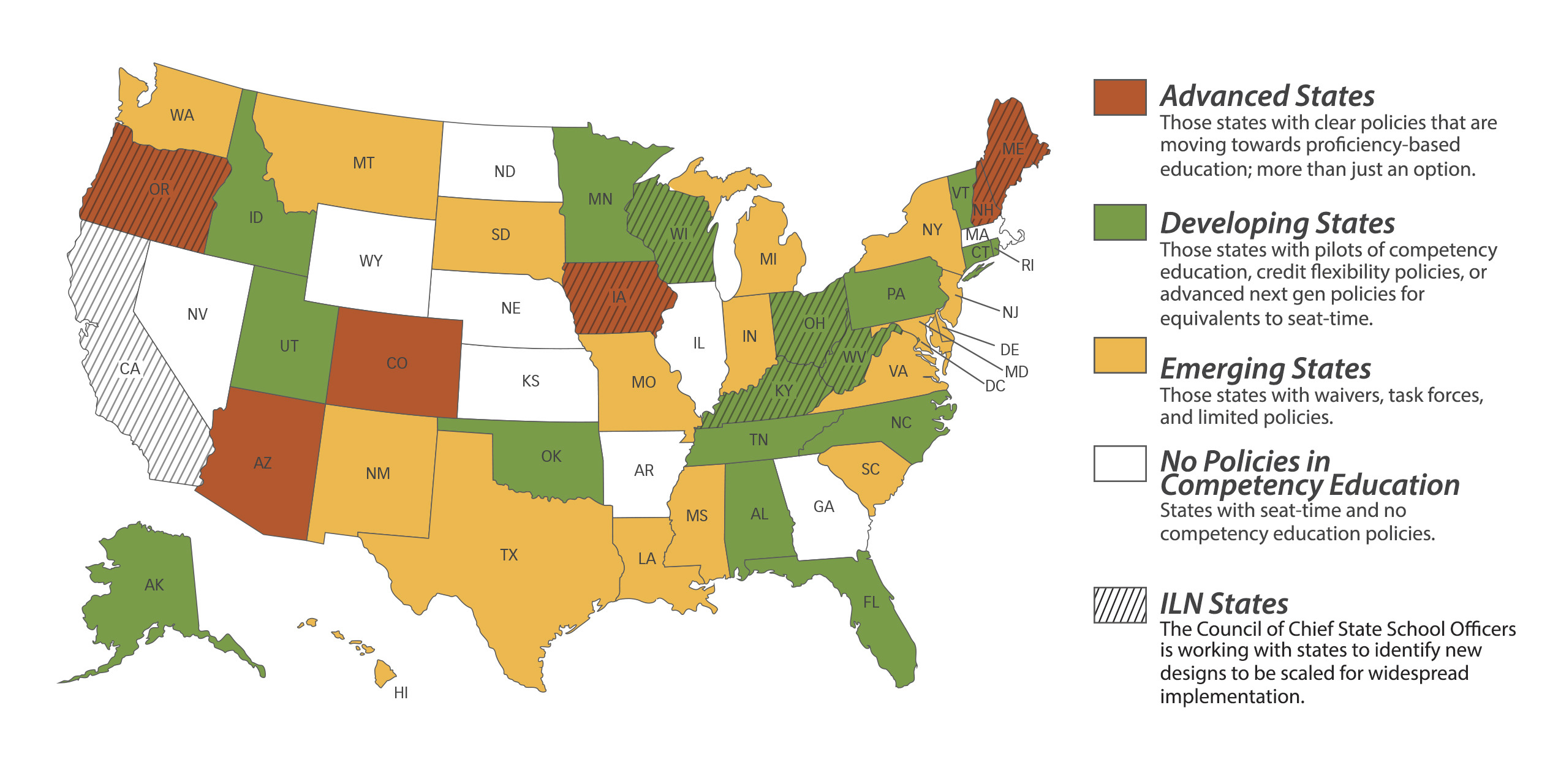

Of course, this is much easier said than done. While more and more schools are allowing students to work at their own pace – and seeing success – no consistent policies exist from state-to-state or district-to-district. Only New Hampshire and Maine have enacted statewide laws to move away from the Carnegie unit, the measure that awards academic credit based on time spent in class. Twenty-nine states allow districts to define their own credits, according to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

As a result of this fragmented policy landscape, there are few models for schools to follow.

For the 2014-15 school year, Piedmont Middle School, in rural northeast Alabama, reimagined how its students learn by letting them progress based on their mastery of skills and standards. Now, as they prepare for the second year of competency-based learning, administrators, teachers, and students are reflecting on the victories and lessons learned.

There were definitely doubts at first.

“At the beginning of the year, I’m pretty sure everybody thought, ‘I need a different school to go to,’” said Lexi, a 7th-grader.

Despite a full year of planning and training, teachers didn’t feel comfortable giving up so much control to students. And when they did give students space, some complained. “My teachers are not teaching me!” one teacher reported hearing from her students.

Teachers often felt overwhelmed by data. Instead of finding valuable insights into how students learn, they initially reported being taken aback by how far apart students were in their mastery of different skills.

What’s more, they realized not every student is capable of working at his or her own pace. “For some kids, ‘self-paced’ means ‘no pace,’” said one teacher. Students noticed the same trend. Some said they weren’t motivated at first because there weren’t immediate consequences for not doing their work.

One of the biggest challenges for public schools is change management. Often there is broad agreement on an idea – for instance, students being able to work at their own pace – while the real struggle is in the execution.

Piedmont’s 1,200 students, 68 percent of whom are from low-income households, aren’t exposed to many opportunities or career paths outside of the classroom. Success is more than just developing a strategy for an initiative. It’s changing expectations so that students who may have never considered college a possibility can not only attend but thrive.

Piedmont is emerging as a national model for the future of rural education because it relentlessly works to provide its students with an education and a skill set that rivals a wealthier district. Every student receives a laptop for school and home. Through local partnerships, all families have access to free and low-cost Internet. Students take computer programming, robotics, and foreign language courses that, until recently, weren’t offered.

There are indications that all of these efforts are working. In 2014-15, 95 percent of Piedmont students graduated, putting it in the top 5 percent in the state. Only 24 percent of those students need remediation at college, more than five points below the state average.

So for Matt Akin, Piedmont’s superintendent, and Jerry Snow, principal at Piedmont Middle, the early struggles with competency-based education were worth it if students and teachers came away with a new perspective. And they did.

As the year progressed, teachers were given dedicated time every week to analyze data and better understand each student’s academic needs. Working in a small school helped because teachers could easily look to peers and administrators to get feedback, tweak, and iterate their approach as they went along.

One veteran math teacher said her comfort level with the new process started as a “four” and is now an “eight.”

Early on, she still taught to the whole class, picking lessons that would meet as many students’ needs as possible. Eventually, she began to use more project-based learning, letting students collaborate in groups based on their common strengths and weaknesses and providing one-on-one support to those who needed extra motivation.

Piedmont Middle also started “Team Time,” a period for students to meet with a teacher, set goals, do team-building activities, and generally work on their own academic and non-academic progress. Each student works with the same “Team Time” teacher for all three years at Piedmont Middle. Each student also participates in “My Time” for more focused work on core academic skills.

Over time, students reported being motivated by each other. Early uncertainty gave way to a motivation not to feel left out. An 8th-grader, Pablo, said he spent a lot of time earlier in the year with his “goof-off group,” which used self-paced learning as an opportunity to not do much at all.

“Most of the time they said, ‘I can just do that later,’” he said. “Then, ‘later’ comes next week when you’re still on that standard and you could be on something else.”

When he saw his “goof-off group” peers start to advance ahead of him, he decided to kick into gear. There were standards that he’d put off for two weeks that he was able to master in three days once he applied himself, he said.

Piedmont is learning from these lessons. This school year, there will be a minimal pace students must follow academically. There will be more structure to “My Time,” and students with special needs will receive more of it. Teachers are encouraged to spend more one-on-one time with advanced students, instead of focusing only on students who are behind.

And of course, Piedmont’s leaders understand students’ own abilities to adapt. Lexi, the 7th-grader, is one of the many students who finished her standards early and started working on next year’s standards before school let out. Piedmont is betting that as more students see their peers achieve these kind of results, the initial skepticism of competency-based learning will subside.

“By the end of the year, I can look at my students and I think they figured it out,” said Darla, a science teacher at Piedmont Middle. “We figured it out. It’s been an amazing year.”