Two of my recently graduated high school seniors, now college students, arrive at my classroom at 7:15 a.m. every Friday morning. As I unlock my door, they ask, “So what are we teaching today?”

The two former students are incredible — they stay all day, acting as teachers and mentors in my U.S. and World History classes. Many college students might prefer to sleep in on days they don’t have classes. Not these two. During a lesson exploring two speeches by President Woodrow Wilson, they circulate, helping students define words, asking others to push their thinking further, answering questions while I’m working with another student. Another day, during a vocab quiz, they watch their former peers, eagle-eyed, making quiet and quick reminders to students to keep their focus on their papers.

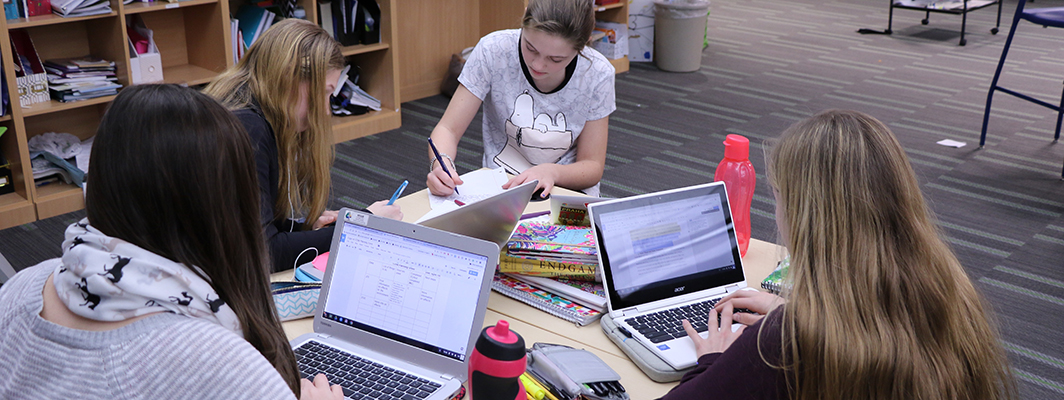

There is a large and longstanding body of research measuring the positive impact of peers teaching peers. The effect is twofold. Researchers have found that learning from fellow students fosters deep understanding of the material and a positive attitude toward the subject matter. But studies have also found that the benefit is mutual — that simply preparing to teach others deepens one’s own knowledge. I see the powerful effects of peer education every week in my classroom.

My two Friday helpers are not my only teacher apprentices. Three senior girls, also former students, have made it a habit to come to my class during their 25-minute lunch blocks. Despite being friends with many of my students, the girls are all business in class — they refocus two chatting students; they remind another to put his cell phone away; they re-explain part of an assignment in Portuguese to a fourth.

In a growing number of settings, educators are capitalizing on the positive impact of students teaching students.

The opportunity to teach your peers sends a powerful message. It says to students, “You have knowledge worth sharing, you have a teacher’s trust, and you have an opportunity to support your friend’s learning.”

Twenty years ago, eighth-graders in Jackson, Mississippi, helped to found the now-national nonprofit The Young People’s Project (YPP). The eighth-graders were all students in the Algebra Project, a math-based education program developed by civil rights leader Robert Moses, when they attended a teacher workshop on how to use graphing calculators. Catching on to the technology quicker than teachers, they became classroom assistants, teaching both their peers and teachers how to use the calculators. They soon began leading workshops in other schools and cities, eventually developing what became YPP, with high school and college students teaching middle and elementary students in afterschool and summer programs. YPP now works with students in nine cities across the country.

The national nonprofit Breakthrough Collaborative trains college students to teach middle school students during a six-week summer program. Many of these teachers are the first in their family to go to college, and they can often relate to the experiences of their middle school students, even as they too gain confidence through teaching. Breakthrough goes further, intensively mentoring most of its students through high school, supporting them with organizational skills, academic tutoring, and college preparation.

In Washington, D.C., the nonprofit Reach Incorporated, founded by Mark Hecker (a Harvard Graduate School of Education alumnus), has found tremendous success in training high school students who struggle with reading themselves to act as reading coaches to second- and third-graders. In the process, the high school students end up strengthening their own skills. Within a single academic year, these high school tutors show, on average, two years of reading gains. The elementary school students they teach show almost as much growth.

In New York, 10 public high schools participate in the Peer Enabled Restructured Classroom (PERC) program which trains primarily 10th-graders to be assistant teachers in ninth-grade math and science classes. Similar to Reach, PERC specifically seeks out students who struggled in math and science, supporting them as they become assistant teachers working in the classrooms of their peers.

The opportunity to teach your peers sends a powerful message. It says to students, “You have knowledge worth sharing, you have a teacher’s trust, and you have an opportunity to support your friends’ learning and growth.” Students teaching students is an authentic way to build confidence, leadership, and empathy.

But the impact is no less for the students being taught. They see in their peers role models with similar experiences and concerns, who can affirm them and also push them to reach higher.

How can we, as teachers, create greater opportunities for our students to become teachers?

In my own classroom, I am continuously struck by the generosity of my students and former students, and moved by how thoughtful they are in supporting their peers.

One Friday afternoon, a group of freshman boys, tucked into a corner of the class, were acting up. Without my asking, one of my college freshmen made a beeline to them. From a distance, I overheard him give them a pep talk, half in Spanish, half in English. “I too used to be the trouble maker in class,” he told them. “I too used to act out.” He paused “It’s not actually as cool as I thought.” I left them to talk things out, knowing I am incredibly fortunate to have such inspiring young teachers in my classroom.

***

This article originally appeared on Usable Knowledge from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Read the original version here.