Executive function — our ability to remember and use what we know, defeat our unproductive impulses, and switch gears and adjust to new demands — is increasingly understood as a key element not just of learning but of lifelong success.

Researchers at the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University describe executive function as an air traffic control system for the mind — helping us manage streams of information, revise plans, stay organized, filter out distractions, cope with stress, and make healthy decisions. Children learn these skills first from their parents, through reliable routines, meaningful and responsive interactions, and play that focuses attention and stirs the beginnings of self-control. But when home is not stable, or in situations of neglect or abuse, executive function skills may be impaired, or may not develop at all, limiting a child’s success in elementary school and later life.

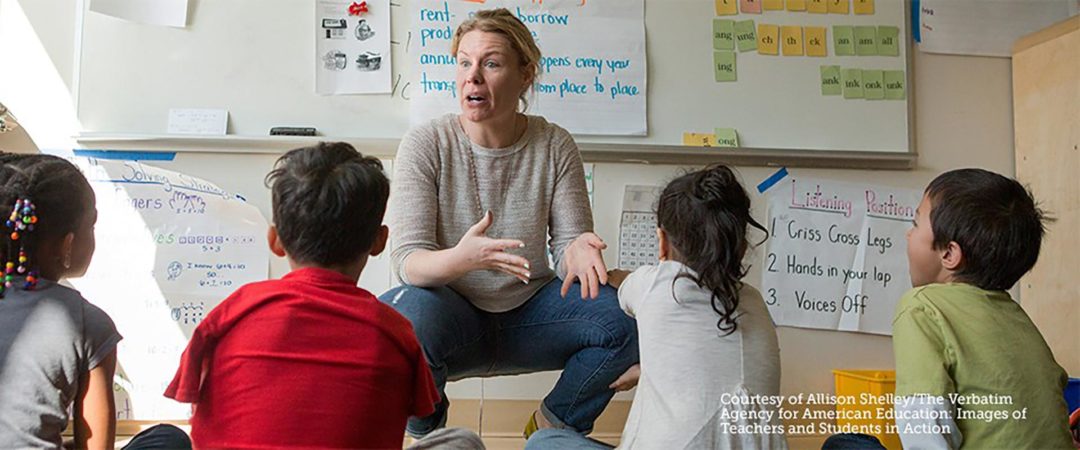

The Center on the Developing Child, housed at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has just released a highly usable collection of resources aimed at helping educators reinforce these skills — or encourage their development in vulnerable children. The guide, called Enhancing and Practicing Executive Function Skills with Children from Infancy to Adolescence, offers a broad range of age-appropriate activities and games to bolster executive function at different stages.

Below, suggested activities for children in the 3–5 age range, a period where executive function capacities spike. These activities are excerpted from a chapter of the guide that can be downloaded individually here.

“During intentional imaginary play, children develop rules to guide their actions in playing roles. They also hold complex ideas in mind and shape their actions to follow these rules, inhibiting impulses or actions that don’t fit the ‘role.’”

Support it by:

“Children love to tell stories. Their early stories tend to be a series of events, each one related to the one before, but lacking any larger structure. With practice, children develop more complex and organized plots,” requiring them to hold information in working memory.

Support it by:

“The demands of songs and movement games support executive function because children have to move to a specific rhythm and synchronize words to actions and the music. All of these tasks contribute to inhibitory control and working memory.” Make sure activities become increasingly complex as children move through the age range.

Support it by:

***

Get Usable Knowledge — Delivered

Our free monthly newsletter sends you tips, tools, and ideas from research and practice leaders at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Sign up now.

This article originally appeared on Usable Knowledge from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Read the original version here.