December 2, 2019 | By Quinn Burke and Emi Iwatani

While there has been considerable focus on developing K-12 computational thinking pathways in major U.S. cities over the past five years, too often rural school districts receive considerably less attention on the national landscape. Our work with the Tough As Nails, Nimble Fingers project (Tough as Nails), which is funded by the National Science Foundation, aims to change this pattern and draw more attention to the resilience, promise, and potential of rural communities to develop their own computing pathways.

Computational thinking represents a series of foundational concepts and practical skills to help students better collect and organize data, draw connections among such data, and develop explanatory models based on such information. More simply, computational thinking is about leveraging digital technology, particularly computing, to address issues of systems and practice, and promoting computers as devices to facilitate better communication rather than just calculation.

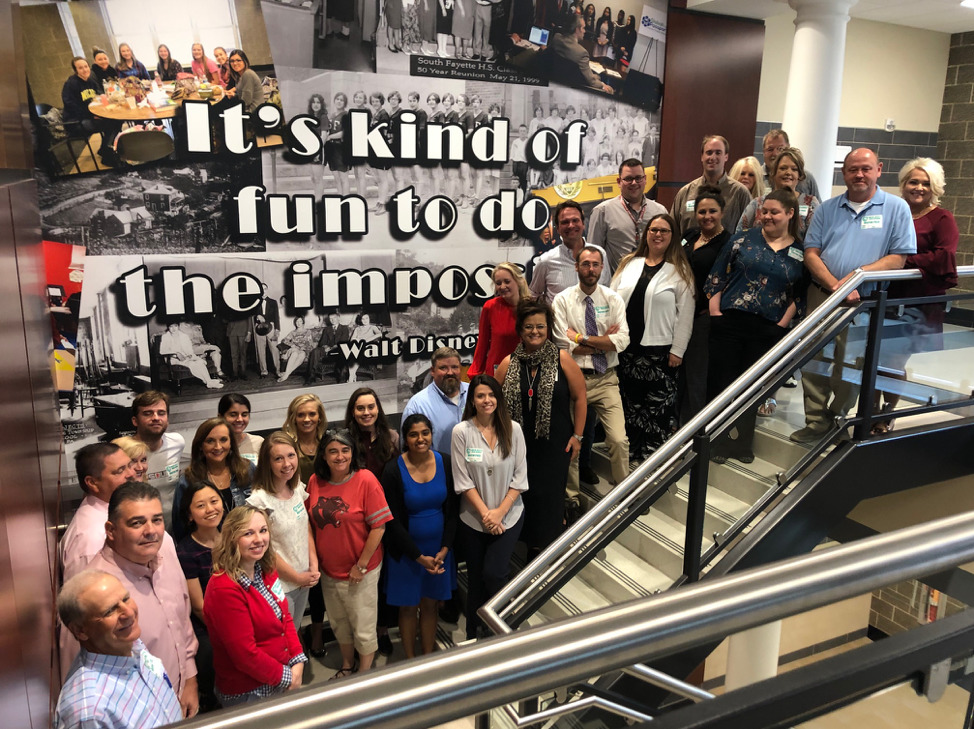

Kicking off the Tough as Nails project, educational leaders from Floyd County and Pikeville Independent Schools convened just outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to think about how schools can adopt computational thinking.

How do you integrate computational thinking in the classroom? This question structured the two-day event at South Fayette School District (SFSD), which has a nationally recognized program for teaching computer science and computational thinking. Forty Kentucky Appalachia teachers, administrators, and school board members drove more than five hours to analyze their conceptions of computational thinking through direct observation and hands-on participation.

Floyd County and Pikeville educators participated in a series of South Fayette School District classroom visits to observe students work and learn more about computing pathways.

The Floyd County and Pikeville teams got a glimpse of SFSD’s comprehensive K-12 computing pathway through the eyes of the students. At the elementary school, the teams tinkered with the interactive digital stories children created using Scratch, a block-based programming language. At the middle school level, they tested the mobile apps students were piloting using App-Inventor and dropped in to one of the country’s first-ever middle school cybersecurity courses. At the high school level, they saw students take their computing projects “public” through the district’s FabLab, which pairs students’ self-designed coding projects with nascent business plans for wider dissemination in the community and even nationally.

Floyd County and Pikeville educators observe and participate in the classroom.

After their classroom visits, Floyd and Pikeville educators reflected on what they had seen. There was visible excitement about implications for their schools and classrooms. One Pikeville teacher shared, “I am excited to start conversations about how we can implement these ideas in our own schools.” A teacher from Floyd County noted “complete 100% interest and engagement” among students, and pointed out that computing had the potential to both introduce new concepts to children and to change pedagogical practices by focusing on more hands-on, authentically collaborative activities.

Understandably, teachers also felt some concerns about the resources, buy-in, and capacity building required to integrate computational thinking in their rural schools. Many asked, “How will we incorporate computational thinking into our scheduling? Will other content need to be cut?” These questions represent the necessary starting point for any school district intending to offer computational thinking. They also represent one of the key challenges of the three-year grant.

Unlike computer science (which exists as a stand-alone discipline) and coding (which exists as a discrete skill), computational thinking is intended to be integrative in nature. Whether deciphering patterns in numeracy and geometry, developing computational models to simulate weather patterns in a science class, or mapping human migration patterns in social studies, computational thinking has the power to accentuate and heighten existing disciplines.

This potential to integrate is both an opportunity and a major challenge. But as the Tough as Nails moniker suggests, the Floyd County and Pikeville teams are certainly up for it. Traci Tackett, director of digital literacy at the eastern Kentucky software start-up Bit Source, points out that resilience runs deep in Kentucky Appalachia. “Central Appalachia has always been a region where people have been recognized for their hard work and independence,” she points out. “Decades of economic dependence upon coal jobs created a false security that dissipated during the recent decline of the coal industry. The educational systems in east Kentucky recognize the need for resilience and are up to the challenge of preparing students for an uncertain and ever-changing workforce. We want students who are well prepared for the jobs of the future!”

Along with South Fayette School District, we will support the local Appalachia schools to understand how computational thinking is not simply an academic endeavor, but can translate to future internships and jobs for the region. “Providing access to high quality computational thinking content in rural communities is a critical equity issue,” says Digital Promise CEO Karen Cator. “We are excited to work with our partners to ensure students in these communities have powerful learning experiences that will set them up for a life of opportunity.”

Check out this blog post and report to learn more about the application of computational thinking throughout education and the workforce.

By Sharin Jacob and Quinn Burke

By Dr. Kyle Dunbar and Katie Wilczak

By Elliott Barnes and Sara Mungall