This connection was explored by Dr. Brooke Stafford-Brizard, vice president for Research to Practice at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), in a recent webinar hosted by Digital Promise on “Research to Practice: Wellbeing, Connection, and Learning.” The session drew educators, researchers, and other stakeholders from around the world—from California to Washington D.C., Ukraine and Jamaica—and is part of a series supported by the Wallace Foundation aimed at connecting research to practice.

Stafford-Brizard shared research, examples, and insights around three key areas:

A well-known body of research from the 1990s on adverse childhood experiences demonstrated the impact of trauma on key learning centers in the brain and centered on the impacts of abuse, neglect, dysfunction, or instability. Since then, Stafford-Brizard explained, the framework has been expanded to recognize “many other contexts of adversity like bias, that children and adults experience” and how this adversity results in chronic stress. Chronic stress prompts a bodily response—a release of the cortisol hormone— which moves us into focusing on survival. She said, “It kind of shuts down…learning centers to make sure that we can focus on that fight, flight, or freeze and take care of ourselves as a mammal.”

This adversity has a far-reaching impact into adulthood. Citing research from Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, surgeon general of California, on adverse childhood experiences, Stafford-Brizard shared that students who experience trauma are 32 times more likely to present with learning or behavior problems. She emphasized that it is the context that impacts the child; “it’s not ingrained or permanent in the child.” And so there are things we can do.

A powerful body of research, said Stafford-Brizard, confirms that “our cognitive processes, how we pay attention, [and] how we hold information in memory is deeply connected to how we feel safe in relationships, and that starts with infancy.” Early on in her talk, Stafford-Brizard spoke to the ways in which our brain and our body are inextricably linked, and how we “evolved as a species because of social connection”—citing Mead’s observation of the healed bone. “We saw that as we connected as a human society and took care of each other, we evolved and moved on, as a civilization, and that is ingrained in our brains.”

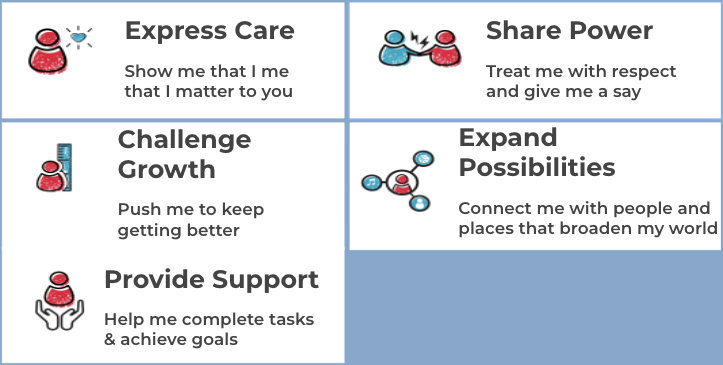

She spoke about the key elements needed to support students and relationships, drawing on the Search Institute’s Developmental Relationships Framework. “We need to provide for students, and that starts with care,” said Stafford-Brizard, “but also expand beyond it and give them the space to be held accountable, to hold us accountable, and to push ourselves.”

Developmental Relationships Framework via the Search Institute. Credit: Dr. Brooke Stafford-Brizard and Search Institute

Stafford-Brizard shared examples of this approach in action at Van Ness Elementary School in Washington, D.C. Over the past several years, Principal Cynthia Robinson Rivers and her staff, with support from Transcend Education and others, have worked to codify “a number of the phenomenal practices…that have driven success in her building [that] she has pulled from many areas of research.” They are shared in greater detail at wholechildmodel.org.

Second, while the larger school culture is focused on relationship-building, Van Ness teachers and staff draw on data from their culture survey to identify specific students who may benefit from more one-on-one time with caring adults. Their “TLC: Time, Love, Connection” practice ensures that each student has a designated adult in the building that they spend one-on-one time with each day, sometimes a few minutes or more if needed.

Finally, students also engage in a “Structured Recess,” where they play games and engage in activities that help them think and work through behavioral issues or other challenges.

The backbone of any school’s effort to implement trauma-informed practices is support for teachers—not just in training or professional learning. Stafford-Brizard named the unprecedented stress many educators feel, citing a recent survey that found the majority of teachers are considering leaving their role earlier than intended. “Almost all teachers [90%] are naming burnout as a significant issue, and we know from research that high levels of burnout, high levels of stress, and low reported ability to cope with that stress, are associated with student outcomes,” she shared. “You cannot have whole children, if you do not have whole teachers.”

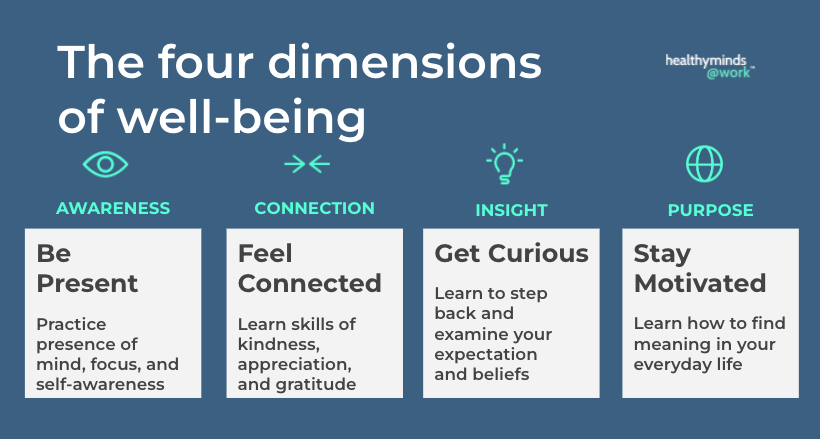

Stafford-Brizard offered strategies from a framework developed by neuroscientists at the Center for Healthy Minds, which has developed an app that focuses on supporting healthy wellbeing through an asset-based lens around four key dimensions:

Credit: Dr. Brooke Stafford-Brizard and Healthy Minds Innovations

Teachers need to feel connected to a community, and part of something bigger. The program (and app) from Healthy Minds Innovations includes a number of tools and guided practices in each of the four areas. In 2020, they worked with school teachers in Madison, Wisconsin, to create a four-week program where teachers spent time each day doing short, daily guided activities in these areas, such as focused meditation or other things that could be done in just 15 minutes or even while doing other tasks such as washing dishes or walking. As a result, the team “found significant drops in psychological distress and loneliness for teachers and increases in mindfulness and that connection to meaning and wellbeing” that showed up at the end of the four-week intervention and in sustained results measured three months later. This is just one of several tools that has shown promise in supporting teachers’ mental health and wellbeing.

In breakout discussions, webinar participants shared other resources and strategies they are using to support student and teacher wellbeing. We’ve compiled a number of those resources, along with resources from Stafford-Brizard and Digital Promise.

Resources from Stafford-Brizard and webinar participants:

Resources from Digital Promise:

Resources on Racial Trauma

“Acknowledging and Coping with Racial Trauma” – Harvard GSE synthesis of interview with Tracie Jones, James Huguley, Sarah Vinson

“Choosing to see the racial stress that afflicts our Black students” – Riana Elyse Anderson, Farzana T. Saleem, and James P. Huguley

“Healing the Hidden Wounds of Racial Trauma” – Kenneth V. Hardy

A video recording of this webinar and discussion is available here. Digital Promise will host more webinars exploring the links from research to practice in the fall of 2022.

We will also host a virtual “Learning Salon” on the topic of Mental Health and Trauma in June 2022, during which district leaders will have the opportunity to meet and engage with solution providers who have tools or programs to support schools in this area. Interested districts may sign up here.