This idea was explored in a recent webinar hosted by Digital Promise on “Research to Practice: Building Systems for a More Solidarity-driven Family Engagement Practice.” Dr. Eyal Bergman, senior vice president at Learning Heroes, shared his research on liberatory approaches to family engagement. The attendees—a global audience of practitioners—engaged in roundtable discussions where they shared reflections and implications for their contexts. The presentation is available to view now.

Dr. Bergman explained that too often, non-dominant families are treated as spectators to the work of schools; their expertise and their wisdom about their children and about their cultural backgrounds and communities is overlooked or devalued. Efforts at family engagement often take on an assimilation function. Born out of good intentions, programs like parent universities and family liaisons implicitly say that the change needs to happen with the families. It’s a deficit perspective. Dr. Bergman describes these as “incomplete strategies.”

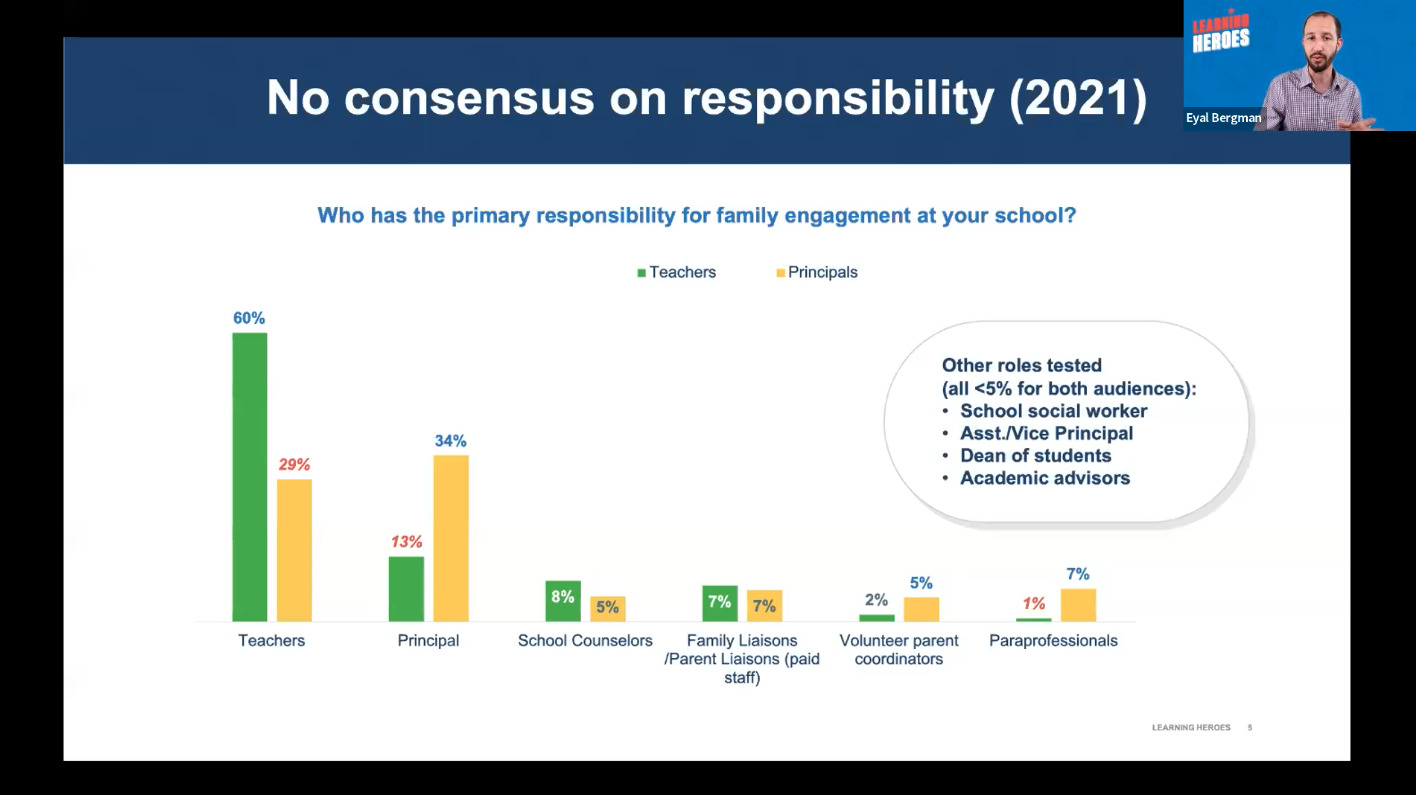

Whose responsibility is it to do family engagement work? In a 2021 survey from Learning Heroes, 60% of teachers reported that it was their responsibility, and 29% reported it was their principals’ responsibility. Amongst principals, 13% reported it was teachers’ responsibility, and 34% reported it was their own responsibility. During roundtable discussions, one participant shared that it was a “red flag” for them that only 34% of principals thought it was their job.

Caption: Survey data shows no consensus on whose responsibility it is to do the work of family engagement. Alt text: Chart showing teacher responses, 60% teacher responsibility, 29% principal responsibility. Principal responses, 13% teacher responsibility, 34% principal responsibility. Other roles (school counselor, family liaisons, volunteer parent coordinators, paraprofessional, social worker, assistant principal, dean of students, and academic advisors, all report < 9% for both audiences)

While these statistics may be alarming, they are not necessarily surprising. As Dr. Bergman explained, “When you talk to administrators who oversee the principals, if family engagement is even on the evaluation rubric, it tends to be the least valued. So principals and administrators don’t necessarily know how to evaluate this work, or they don’t have a good sense of what constitutes really good practice.”

These challenges are layered on poverty, and impacted by historical marginalization, oppression, and long-standing inequities between families and schools. When schools seek to improve family engagement, if challenges that occur in the day to day interactions between families and schools are not addressed, family engagement programs will fail. . As one participant shared in the roundtable discussion, “My community respects the education system, but they don’t see their place in it.” At its core, family engagement is equity work. Done well, Dr. Bergman believes this approach can be a strong key component of a district’s equity agenda.

Dr. Bergman’s research calls for a “new normal” in family engagement that is liberatory, solidarity-driven, and equity-focused. Liberatory means that it is free of dominance, of oppression, and free of existing power dynamics that play out between home and school. This means sharing power in decisions like these: What gets talked about when parents and teachers engage with one another? Where will the meeting take place? What language will be used? Who initiates the phone call? The recommended approach requires deeply listening to families and seeing them as allies and partners in the work of education.

There are three pillars to this approach, which Dr. Bergman explains in Unlocking the How: Designing Family Engagement Strategies that Lead to School Success: trust, student learning, and infrastructure. First, trust and teamwork must be at the center of the home-school relationship. Sometimes this means focusing less on communicating information between parties and focusing more on building, and sometimes restoring, relationships. Second, the purpose of family engagement is to make positive changes in student learning. Engagement strategies that are anchored in student progress, goal setting, and well-being are more likely to lead to positive changes for students.

The third pillar, infrastructure, refers to the importance of investment in the systems and structures that enable this work. Dr. Bergman’s research indicates that it takes leaders at the central office level to marshal this work in a way that is embraced by all leadership, integrated in all strategies, and sustained with resources. Key actions for leaders include:

When school leaders modernize their approach to family engagement and address family engagement as an equity issue, the end result is educators who are empowered to connect family engagement to learning and development, honor family funds of knowledge and create welcoming cultures. Families participate in diverse roles as co-creators, supporters, encouragers, monitors, advocates, and models.

This webinar was an extension of Digital Promise’s work sponsored by the Wallace Foundation on principal leadership in a virtual environment (2021). This webinar is the first in a series, with the goals of continuing the conversation and further advancing school leaders’ understanding of current, critical topics and their application in their learning environments.

Next, on September 22 2022 at 12 p.m. ET, we’ll host Dr. Judit Moschkovich on the topic of “MATHEMATICS AND LANGUAGE: Supporting English Learners in Mathematics Classrooms” You can sign up for that webinar and the full series on our Eventbrite.

Want to know more about family engagement? Below are resources recommended by Dr. Eyal Bergman, as well as resources from Digital Promise.

Follow @DigitalPromise on Twitter to stay updated on upcoming research-to-practice webinars and events. Dr. Bergman also invites you to follow him on Twitter at @EyalBergman and @bealearninghero.