June 5, 2019 | By Emi Iwatani, Maria Romero and Barbara Means, Ph.D.

Science teachers juggle myriad responsibilities—fostering inquiry skills, addressing state instructional standards, supporting math and literacy, and the list goes on. Especially to those who have curated their lessons to satisfy so many different objectives, it can feel risky to give up some structure and allow students a significant degree of choice and control over their learning.

Yet, as we shared previously, 18 teachers from three districts in the League of Innovative Schools have pushed themselves to do just this. Challenge Based Learning (CBL) is a type of project-based learning distinguished by its insistence that students engage with, investigate, and act on authentic and motivating challenges. In accordance with this model, participating middle school science teachers designed phenomena-based lessons where students, rather than the teacher, came up with questions to pursue. In this blog, we share initial research findings on how teachers, many for the first time, asked their students to lead their own learning within the context of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), and what happened when they did.

After reviewing core ideas of CBL and NGSS, teachers worked in teams to design five-day units that encourage students to come up with science questions that lead to a motivating challenge. Easier said than done, this design effort required educated guessing and perspective-taking on the part of teachers: What challenge(s) related to core science concepts would students find interesting? What phenomena would lead students to ask questions related to these concepts? How can the questioning process be guided without being overly constricted?

Teachers spent three or more days co-designing and preparing for the lessons. Topics included:

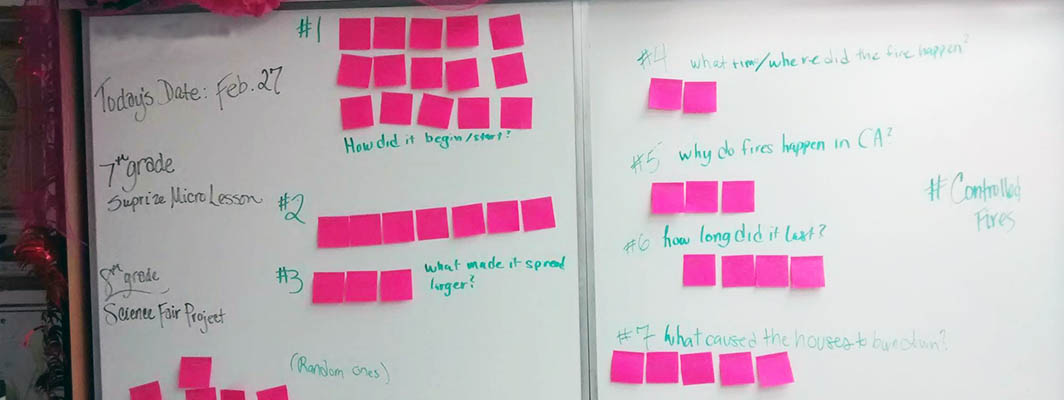

Teachers incorporated student questioning in their lessons, asking students to figure out what they wanted and/or needed to learn and investigate, and providing students with a great deal of space to investigate or design on their own.

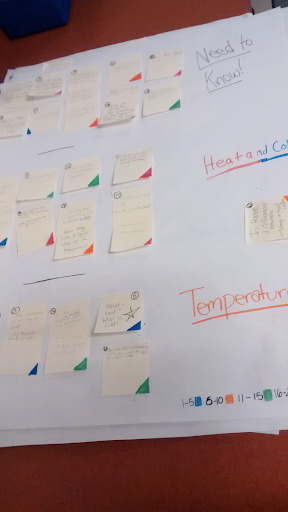

A board of organized Post-It notes from a seventh grade class. In the class, each student generated as many questions they could think of on designing a good thermos, pooled their questions in a small group, and prioritized and organized their own questions.

Through their CBL lessons, teachers frequently asked students to make consequential choices about their learning. For example, students themselves had to consider what they needed to know (e.g., to create a device that blocks cell phone signals). One teacher described this as “a backwards way of doing things [compared to prior practice]” where instead of frontloading students with concepts and vocabulary, they “let students practice and play” to figure out what the science concepts actually mean.

Giving students so much control was a source of trepidation for many of the project teachers. Some worried whether they could be quick enough on their feet to respond to student questions they hadn’t anticipated. Several also worried whether students would come up with good questions, or be able to carry out investigations and designs on their own.

Many teachers prepared themselves with categories of questions that students might ask, and thought through how they would respond to each. Some rehearsed their lesson during professional learning community (PLC) meeting time at their schools, having their colleagues playing the roles of students and friendly critic.

Teachers were pleasantly surprised by the way their students took up their new freedom and responsibility. A seasoned teacher, who characterized her usual teaching style as “very structured,” found that “the kids really liked the ownership portion … and I really feel that this works.” She added:

“Oftentimes when I’m teaching or asking questions, it’s the same hands that are raised or the same hand [of the] same kids [who] have questions. [So] I liked the fact that through [CBL] questioning and the research, every student had the opportunity to voice their opinion or provide feedback. I thought that was really, really cool.”

Another veteran teacher similarly characterized her new lesson as “very student driven” and reflected:

“I was sort of apprehensive at first because I didn’t know that we would be able to kind of push them down the avenue that we needed for their challenge questions here. I didn’t know if we’d be able to keep them on track, so to speak. And what I was especially surprised and delighted about was the buy-in of the students. Because they enjoyed the topic and the lesson, I didn’t have to worry about that. They drove the lesson.”

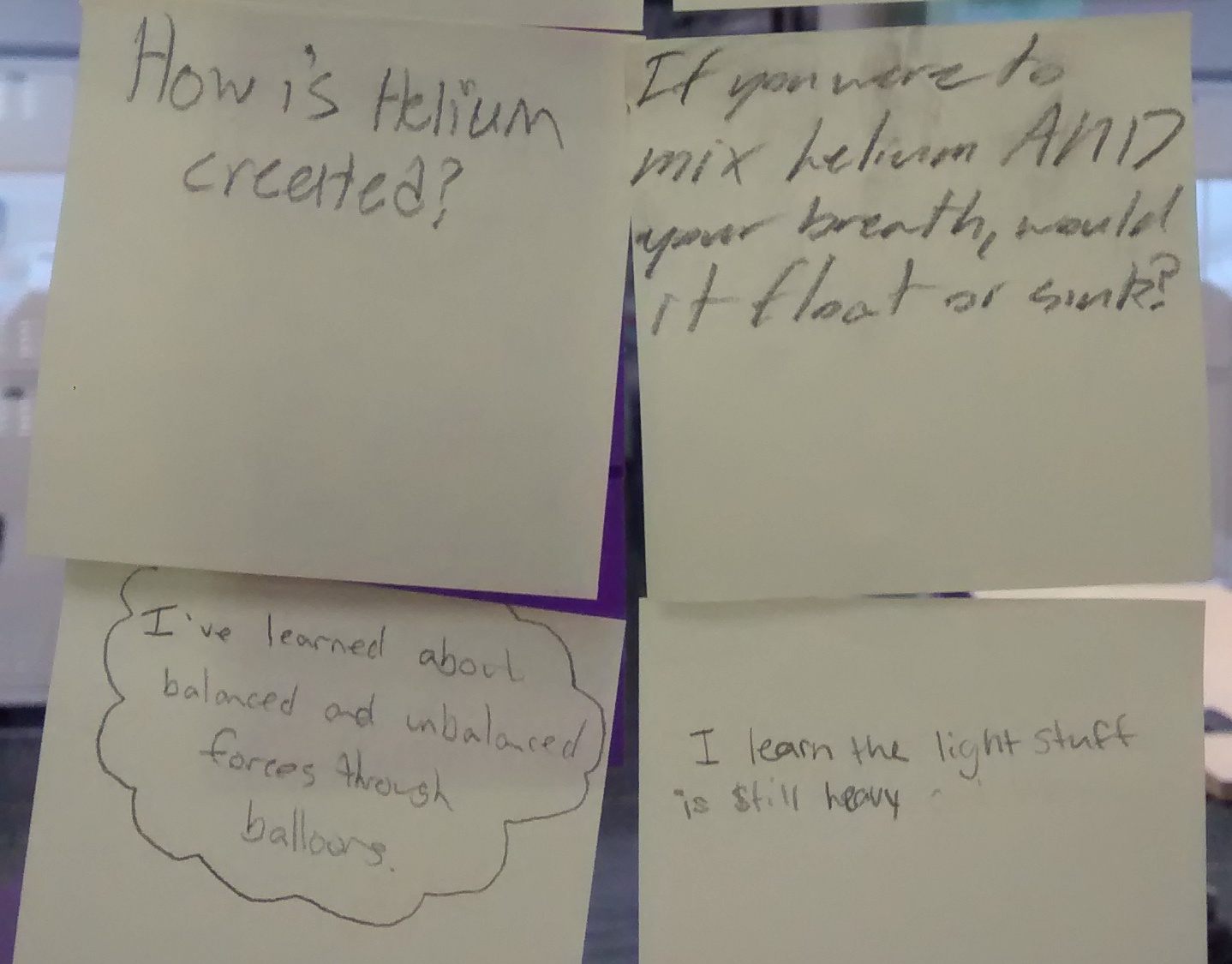

Post-it notes from 8th graders who shared their “I got it!” and “I still wonder…” questions and thoughts after using helium balloons to investigate how blimps might suspend in the air.

District and school leaders supported teachers’ risk-taking in a number of important ways, including finding release time and resources, expressing support and appreciation, and providing instructional leadership. Some leaders rolled up their sleeves and worked on creating a CBL lesson right alongside the teachers. Teachers reported that these concrete expressions of support from their leaders were essential to their willingness to move outside their comfort zone.

Teachers are still grappling with the challenge of finding the right amount of guidance and student choice within CBL activities. They are also wondering about good ways to assess student learning in the context of challenge activities. The Digital Promise research and development team is working to support the teachers in their lesson refinement, and in identifying important learnings from their collective experiences.

Please stay tuned for future blog posts that will feature teachers and district leaders sharing their experiences and takeaways from this project.

Are you interested in bringing Challenge Based Learning to your classroom? Explore the CBL Framework for resources and subscribe to our newsletter to receive the latest on this project.

By Elliott Barnes and Sara Mungall