January 22, 2020 | By Barbara Means, Ph.D. and Jeremy Roschelle

This question drives Digital Promise’s Learning Sciences Research (LSR) team. We sat down with co-Executive Directors Barbara Means and Jeremy Roschelle to find out more about the LSR team’s aspirations and guiding values.

Barbara Means (BM): Because Digital Promise convenes innovative networks of schools and school systems, our education researchers have unique opportunities for ongoing discussions with education leaders around their high priority problems of practice. We’re engaging with some of the country’s most forward-thinking districts through the League of Innovative Schools (League), not just sitting in our offices speculating about what educators would like to learn from research.

Jeremy Roschelle (JR): The opportunity for sustained relationships with districts brings new possibilities to our research. There’s a big contrast between working with a district where there’s a long-term relationship, trust, and mutual commitment to working together, versus a standalone research project, which confines the relationship between schools and researchers to collecting one specific data set. Another aspect that is not typical for learning sciences research is the engagement with central office and school leaders in addition to teachers and classrooms.

BM: I want to underscore that “in addition to.” We recognize the importance of working with classroom teachers and students. Including both leadership and front-line implementers helps ensure buy-in and scaling.

JR: The League helps us think about scaling across districts. When we’re working on a particular research effort with a few districts, it’s helpful to think concretely about how that learning might be useful to 100 districts. Scaling can be built into the beginning of a project in a way that is not often possible elsewhere.

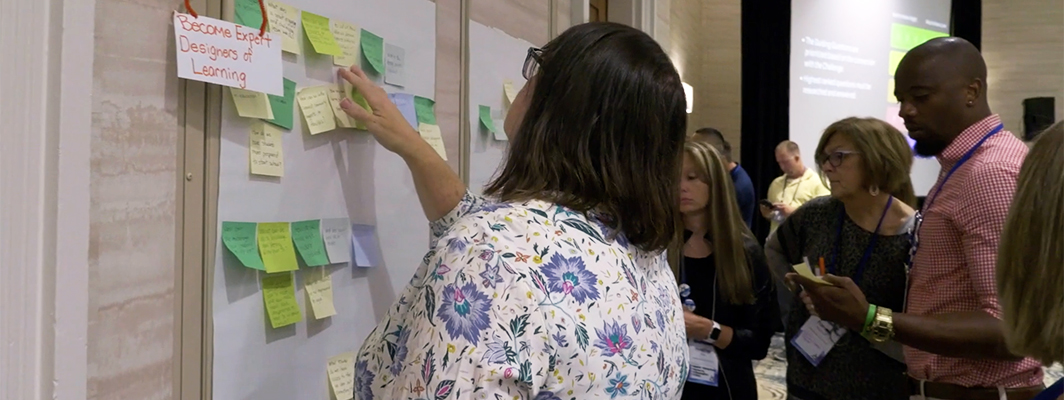

BM: League Challenge Collaboratives provide a rare chance to have both depth and breadth of interaction with districts. The fact that we work with a core group of three or four districts means that not only do the districts each individually give us information about their context and concerns, but they are also supporting and learning from each other. We’re privileged to be part of those conversations because we gain insights from hearing how they coach one another.

JR: At Digital Promise, we start with the Challenge Map, which highlights educators’ priorities in their own language. This tool is unique because it starts from practitioners’ framing. We strive to meet with educational leaders from the beginning of any research project so the research design is done in partnership. A great example of this is the Computational Thinking Pathways project. League districts had already been meeting for a year to talk about computational thinking, so there were examples of districts moving forward with this work… [and] we were able to frame research ideas within that real-world context.

BM: Our ideal project is a partnership between an educational institution and Digital Promise researchers in which the goals of producing better outcomes for that institution and producing generalizable knowledge for the field are in balance. We’re applying our knowledge of the learning sciences and research methods to challenges that are high priorities for our district partners. Because these challenges are priorities for the districts, districts make the time to engage with us around the collection and evaluation of evidence.

BM: Most of our projects involve a diverse set of partners, often including researchers with a range of expertise, data scientists, education leaders, teachers, learning technology providers, and organizations providing professional learning services for teachers. In addition, we’re working to find meaningful ways to expand the role of students in our projects. Each of these groups bring key expertise, and a diverse set of partners produces ideas that are both more creative and more likely to be sustained after the researchers and technology developers are no longer present.

Good learning experience designs benefit from the knowledge of teachers, students, and community stakeholders about the context in which the learning will happen. Collaboration also triggers a shared commitment to trying the innovation and making it work. Projects are more successful when more folks had a hand in the design process because they believe in the design, and they have a vision of how it can work in their particular setting.

JR: One of the things I think we, as researchers, bring is the ability to sort through all the claims about what works to improve education, debunk weak theory, and focus on the evidence. We’re good at taking insights from multiple settings, synthesizing what the findings have in common, and sharing that knowledge back to make it usable. Research-practice partnerships highlight the need for diverse perspectives to move the needle on student learning.

Learning sciences hasn’t just been a lab science or researcher-driven enterprise. It has emphasized co-design processes throughout its history. Some of our early learning projects, for example, demonstrate new ideas about how to involve parents and teachers in the design process. Our researchers bring that valuable practice to the table.

BM: We intentionally listen to stakeholders with diverse expertise and “work with” them throughout the research process, partnering to make a difference together.

Check out the Learning Sciences Research page to learn more about our work and subscribe to Digital Promise’s Learning Sciences Connections newsletter to read stories that share useful findings from the research community.

By Sharin Jacob and Quinn Burke

By Dr. Kyle Dunbar and Katie Wilczak

By Elliott Barnes and Sara Mungall