October 18, 2021 | By My Nguyen

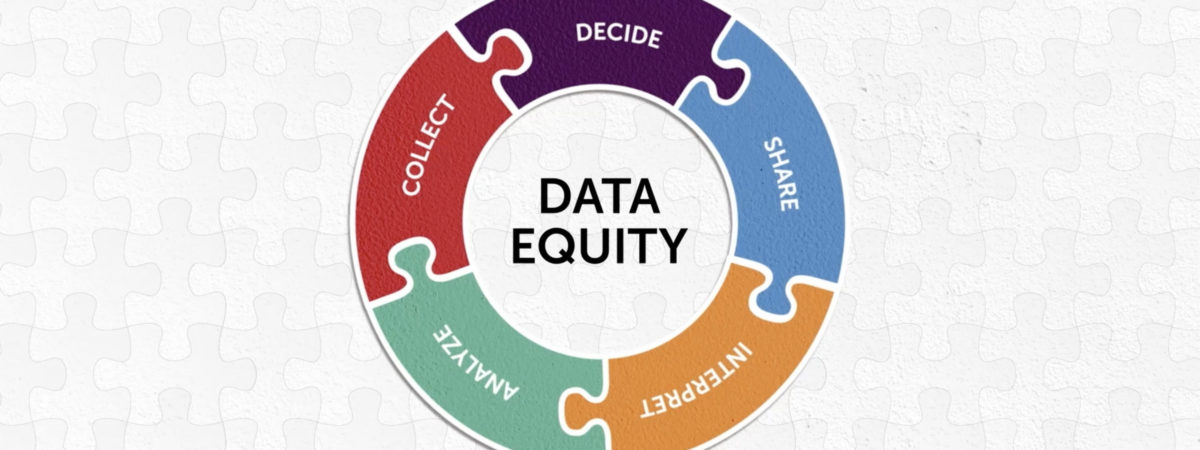

Data equity applies an equity-centered lens and mindset to ensure data is collected, analyzed, interpreted, and shared with diverse stakeholders without bias or exclusion. It enables schools and districts to make informed decisions by ensuring diverse stakeholders are authentically engaged throughout the data cycle.

In the Digital Promise Data Equity cohort, districts are engaging in an Inclusive Innovation research and development (R&D) process to identify equity gaps within their data systems and create action plans to use data interoperability to promote deeper understanding and more equitable outcomes in their schools. Districts participate in a peer learning cohort led by a peer coach and receive individualized support from technical and data equity advisors.

Minneapolis Public Schools (Minnesota) already uses data to inform decision-making in more than 70 schools across the city, but they wanted to find best practices for interoperability to link different systems together for more accurate and timely data.

In addition, the district wanted to examine how that data is applied and how they might address the disproportionality of student outcomes across races in their student population. The focus of the Data Equity cohort aligned “perfectly” with what they were seeking to accomplish.

“We looked at it as an opportunity to hear from other districts and their journeys towards interoperability,” says Justin Hennes, the district’s senior information officer. “It also gave us some more focus to really start having these conversations and collaborate more with teams across the district.”

“The notion of data interoperability as an equity tool itself was something that hadn’t really been on my radar. Now, I think it’s critically important to the work that we do, and to making our data equitable in the district,” says Callie Vaughn, data scientist at Minneapolis Public Schools.

In working through the Digital Promise Data Ready Playbook—a resource designed to support districts with creating an effective interoperable data solution—the Minneapolis Public Schools team identified a tool they wanted to revamp by engaging more teachers and staff.

The tool originated as a ninth grade “on-track tool,” acting as a predictor of whether a student is going to graduate based on their performance in their ninth grade school year. Now, the district has expanded its use to grades 6-12, pulling in core course information (e.g., English, math, social studies, and science) as well as attendance and behavioral data to provide a more holistic view of all students.

“The tool we’re looking at goes all the way from helping staff identify which students are going to need additional support at the student level, and goes all the way to the aggregate level and giving school leaders reports on which of their student populations are struggling in specific areas,” says Vaughn. The tool can also identify staff members who might need additional support in engaging students.

For example, an English teacher would have the ability to check the tool and see that a student’s math teacher had recently contacted the student’s family. Using this information, the English teacher could coordinate with the math teacher to determine a strategy for increasing engagement and support.

“The big thing is trying to get data into one place to make it more equitable and accessible by staff,” says Abby Wolf, an IT strategy process analyst for the district. “We’re looking at the ways we can have an impact and change and repair the foundation of all of our data.”

The district is also working to make data more accessible to families. This year, they are working to launch the “Grad Tracker” in their student and parent portal to more clearly show students’ progress toward graduation in relation to their course sequences.

“We’re trying to give students and parents access to that so they can see [the progress] rather than trying to read a transcript that doesn’t help. You need a visual to see exactly what gaps there are to have conversations with school staff or a counselor,” says Hennes.

To further support family engagement, the district’s parent participatory evaluation group engages five cultural groups (Somali and East African, Black/African American, Native American, Hmong, and Hispanic/Latino) to provide feedback on areas the district could improve. Evaluation specialists train parents and caregivers to become evaluators for questions they have about data and to gather data from their communities. To ensure family perspective is not only heard but incorporated into the decision-making process, members present their findings and their recommendations to district leadership.

The district offers a similar program for students to engage in projects to survey their schools and come up with recommendations for issues including dress code, interactions with the disciplinary system, and school lunch.

“They’re not necessarily interacting with data systems that we have designed, but they are collecting their own data,” says Vaughn. “It’s a way for students and families to take ownership of data in the district.”

The Village of Roselle, New Jersey, was the first community in the world to be illuminated by electric light by Thomas Edison. Today, Roselle Public Schools is steadily making gains to dispel myths and buck the imposed label of “under-performing district.” The district’s participation in the Data Equity cohort is helping them set a clearer vision for the future.

“The pandemic exposed where we needed to really prioritize [efforts]—how we were using data to make both day-to-day, simple decisions to complex decisions,” says Dr. Nathan L. Fisher, the district’s superintendent. “A lot of times, we just look at surface information and we go with it. This process has allowed us to start to look and get to the root cause of some of our problems.”

Like many districts that were forced to quickly pivot to emergency remote learning, Roselle did not have 1:1 device access for students prior to the pandemic. The district acted quickly to fill gaps to ensure the continuity of learning by implementing a new learning management system (LMS) called Schoology. In addition, the district strived to understand which students and families in their community were already connected to the internet, and who might require additional support and access. All of this added to an already overloaded, disparate data structure within the district.

Roselle Public Schools has a “wealth of data.” But that data has traditionally been isolated and presented and analyzed in silos. During the pandemic, the district was tracking not only assessment, but also student attendance and whether learners were logging into classes—however, none of their data systems communicated with one another. Without interoperable systems, the data cannot provide a holistic picture of student opportunities and outcomes.

“When I found the Data Equity cohort, I already knew that our [students’] test scores did not really reflect what our children are capable of doing,” says Karen Tanner-Oliphant, district supervisor of research and assessment.

“What also runs parallel is trying to put out relevant data to the community. If you’re only getting one side of the picture of Roselle, that’s what you’re stuck with,” adds Dr. Fisher. “What other measures that currently exist within our district can we utilize to highlight our growth? This data has been of paramount importance as we engaged our school community through the district’s Strategic Planning process. The district strategic planning process allowed us to share the State of the Roselle School District which encompassed a variety of data points that will guide our vision into the future.”

By working through their data challenges in a supportive peer setting, the district hopes to disrupt those siloes, identify strategies for “recalibrating” curriculum, and accelerate student learning following year-long school closures due to the pandemic. They’re also leveraging the cohort as a research-driven professional learning community.

“We come to the table with a lot of qualitative data—how do we feel about it? what’s your opinion?—but when you look at the data, that kid who you think is not paying attention is actually in great shape. So, that brings up bias,” shares Tanner-Oliphant.

As part of a larger, data-driven strategic plan, Roselle has updated policies on equity across all schools and grade levels. According to the district, staff have deepened their understanding of how student achievement and experience is intertwined with their own biases. They’re also supporting an initiative to make data visible to all stakeholders by going into the community to co-design and redesign district processes. One idea the district has is to develop a publicly-accessible data dashboard on every school’s website to raise accountability and fully engage families and community members as partners.

“Most of the work we do is focused around some form of data, and to have [data equity] as a pillar in our efforts is critical,” says Dr. Fisher.

To learn more about data equity, readiness, and interoperability:

By Elliott Barnes and Sara Mungall