As distance learning continues, teachers are creating and implementing authentic learning opportunities while physically separated from their students. For example, Jessica Bibbs-Fox, a teacher in Compton Unified School District, transformed the COVID-19 pandemic into an authentic, project-based learning experience that integrates computational thinking practices into her virtual middle school science class.

Using the COVID-19 pandemic as the anchoring phenomenon, Bibbs-Fox designed a unit in which students examined the accuracy of information related to the virus. She adapted computational thinking resources from Digital Promise to support students with Collecting, Analyzing, and Evaluating Data and Communicating Data.

Bibbs-Fox acknowledges that computational thinking is a skill set that is new to many students. To support her students in the process, she broke down each step, beginning with having students ask questions based on their curiosities about the pandemic.

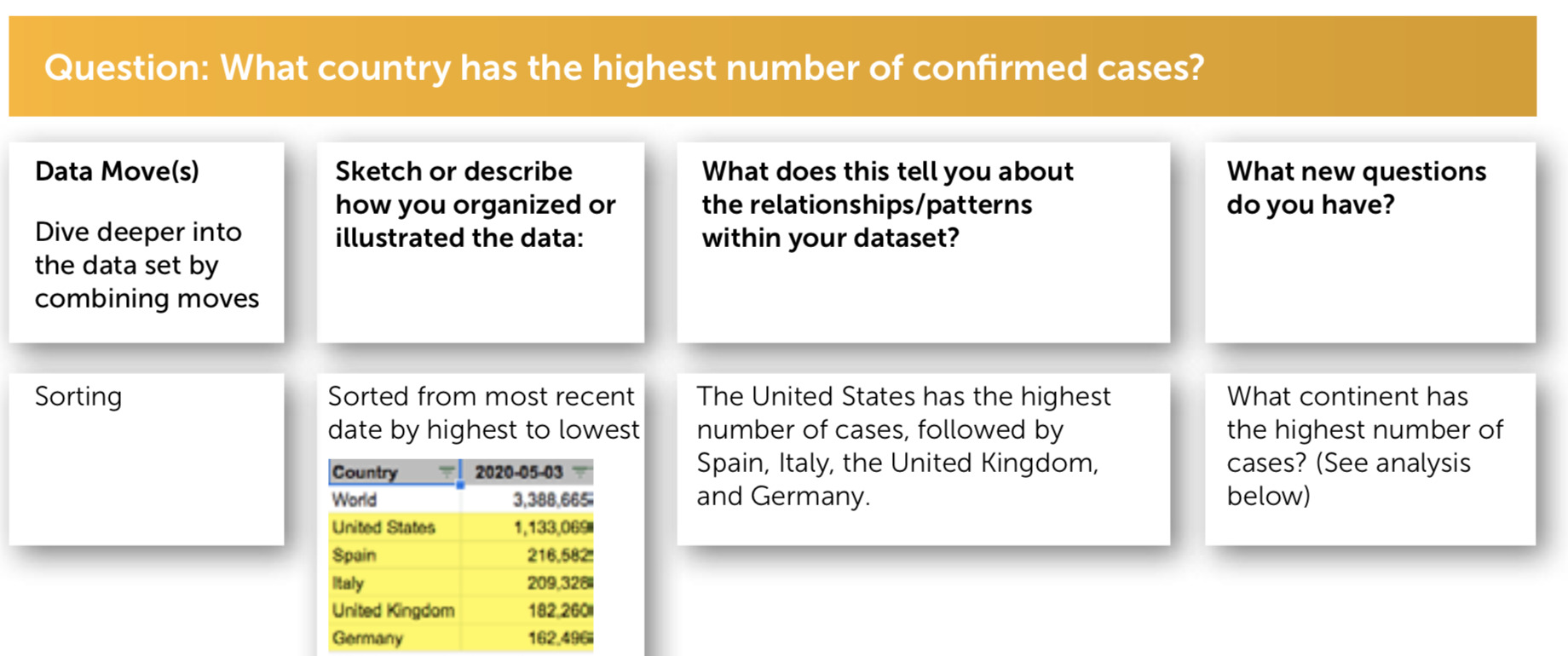

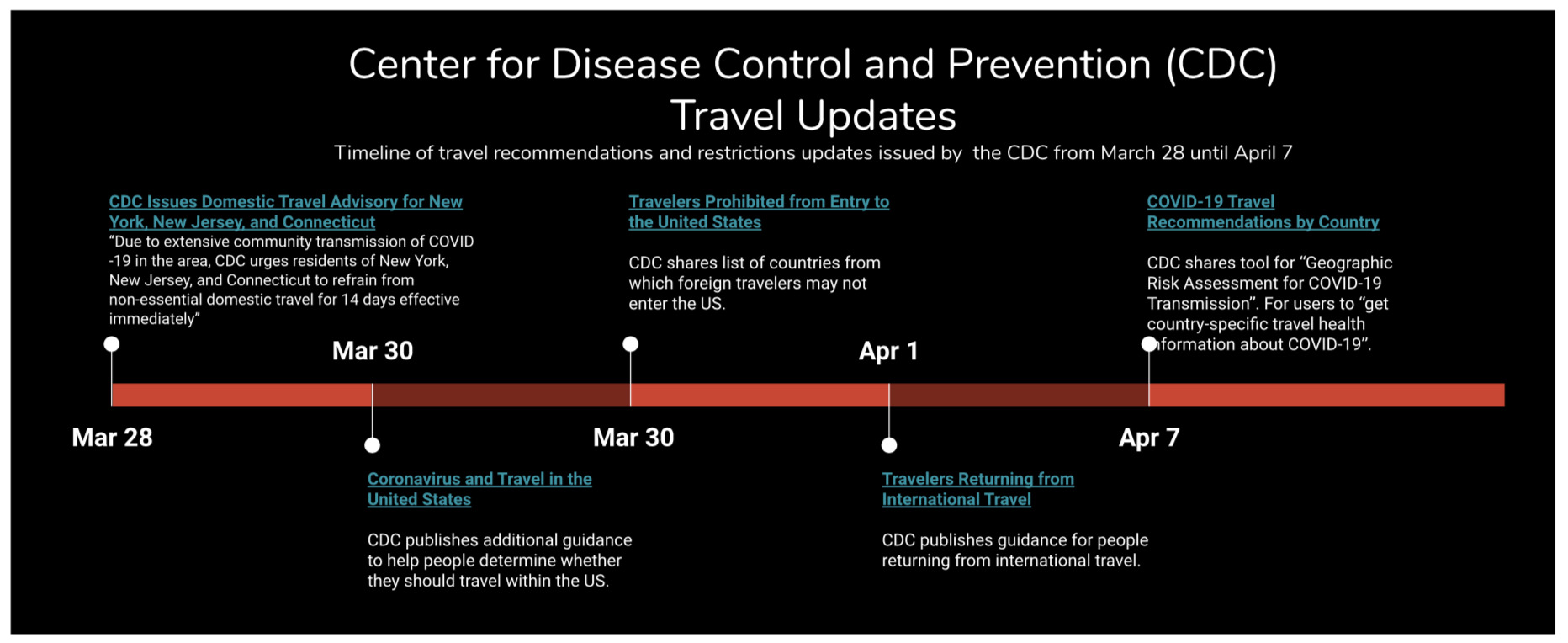

To inform their questions, students used raw data from various organizations and analyzed the datasets using data moves. Throughout the process, they considered the relevance, validity, and bias of each data source.

Bibbs-Fox did not anticipate that many students would struggle to generate questions that could be explored using data. For example, one student wanted to know, “Why is the coronavirus so deadly?” She helped her students make connections to what questions could be answered using the data available to them by posing questions such as, “Why does this fact exist?” and “Is there data to support it?” With these prompts, the example student modified their question to, “Compared to other coronaviruses, is COVID-19 resulting in more deaths?”

Next came manipulating the data in spreadsheets, a new and somewhat intimidating skill for many students. However, Bibbs-Fox reported that this activity helped students to resolve a fear of seeing spreadsheets and feel a certain level of pride in working with them.

“Together we are exploring statements about our questions and asking, ‘What data supports this statement? Where is this data? Let us examine that data ourselves and see if these statements are factual? How can we filter this data to look at one particular aspect of our question? What are we finding that is different from popular or accepted thinking?’” – Jessica Bibbs-Fox

After students analyzed data related to their question, they designed an infographic, created a public service announcement, or wrote a magazine article for members of their community to inform them about their findings. The students targeted community members who were uncertain about safety practices or skeptical about social distancing.

When designing their final products, some students searched for visualizations previously created by outside sources. In response, Bibbs-Fox presented misleading graphics from supposedly credible sources and asked her students to spot errors. They discussed the problems and used them as motivation to use the raw data to create their own visualizations. Students shared their visualizations with members of the community and modified the design based on their interpretations.

“They are starting to see themselves as scientists and understand the nature of science as a human endeavor.” – Jessica Bibbs-Fox

Bibbs-Fox said this project is the most authentic project-based learning experience she has worked on with her students. She explained, “This project relies on questions that do not have answers readily available to them. Students have to rely on their skills to be successful.”

Interested in more on computational thinking? Take action: