Districts in the Digital Promise League of Innovative Schools have identified data interoperability – the seamless, secure and controlled exchange of data – as a serious challenge in maximizing the potential of the many digital tools and resources offered in their classrooms.

The following explores one League district’s journey to advancing data interoperability within its context — Cajon Valley Union School District in southern California. You will also hear from district leaders in the League of Innovative Schools in Mineola Union Free School District (NY), Fox Chapel School District (PA), and Gurnee School District 56 (IL) about what the data interoperability challenge means in their context.

While there are many data interoperability pain points, the following are the most pressing — implementation, rostering and login management, data privacy and security, and secure data transfer between applications. This case study will explore the challenges and solutions offered across the field, and ways to advance data interoperability in your district…starting now.

At sixteen years old, Izela Jacobo was at the top of her class and had plans to become a lawyer. Then, she moved from Mexico to the United States. Izela found herself placed in academic classes below her ability level when she entered an education system that wasn’t ready to support her as a language learner.

Today, Izela is a school principal and can be found buzzing around classrooms at Bostonia Language Academy, an elementary school in the Cajon Valley Union School District. The school is only three years old, and was designed by Izela and her team to specifically support language learners. Forty percent of the students are learning English for the first time, and sixty percent of students are learning Spanish for the first time. Most core classes are taught in Spanish early-on, and by fourth grade classes are split evenly between English and Spanish.

Bostonia Language Academy doesn’t just teach Spanish and English. By the time students graduate, they are expected to be fluent in three languages – the third is coding.

Each classroom is named after a Spanish-speaking country and the doors are adorned with the country name, its associated flag, and an image of a popular character from one of the many apps the students use to learn how to code.

To Izela and her team, coding requires both literacy and communication. Izela explains, “With English and Spanish, they’re able to speak to two-thirds of the world. With that third language we’re giving them, they can communicate with anyone in the world successfully.” It is their opinion that immersion in multiple languages, including coding, must come early.

To support this audacious goal, the school’s leadership provides a device to every student and supports learners with a variety of apps.

Teachers aren’t just using the technology to support learning English and coding. According to Izela, the tools provide the opportunity to individualize and personalize instruction in a way that wasn’t possible before. With students leveraging programs that adapt to their individual needs and skills, the teacher has the time to give others the individualized learning experience they might require.

As great as all of these digital tools have been, the influx of technology has raised new challenges.

These digital tools collect information in different ways, and without a unified system, teachers look at various data points and try to make decisions about how their students are progressing and how best to support them. This is not only time-consuming and inefficient, but in many cases, it’s not secure.

Principal Izela Jacobo describes a typical scenario: some of her math teachers use between four to six different applications to support instruction. Each one of those applications collects and shares data in different ways. To figure out how any one student is doing in math, a teacher might have to open six different dashboards; that does not include accessing state assessment and/or behavioral data.

The term for systems that can talk to each other is data interoperability – the seamless, secure, and controlled exchange of data between applications. This lack of interoperability in education has become a significant barrier to using digital tools to their full potential. And, it is a barrier to Principal Jacobo’s ability to provide seamless instructional supports across languages and subject areas.

For Dr. David Miyashiro, the superintendent of Cajon Valley Union School District, the full potential of technology is tied to the information the tools can provide to support teachers and students. He says, “Tools and data help us capture the student lens so that teachers are able to intervene at the right time. Most districts focus on the devices, the programs, and the apps – but it’s really about the data, the learning, and knowing if the work we’re doing is having an impact.”

This perspective comes from experience; before becoming a superintendent, David was a principal and also taught at the kindergarten, middle school, and high school levels. He repeats the district’s vision often: “Happy kids engaged in healthy relationships on a path to gainful employment.” With 26 schools and 18,000 students, Superintendent Miyashiro credits the shift to digital technology as vital in reaching this vision.

He is also quick to credit the district’s success in supporting this technology-rich environment to the IT department. “Moving from a technology desert to a robust one-to-one [one device per student] environment was not without its bumps and bruises,” Superintendent Miyashiro notes, “but it was the right work and our technologist, Jonathon, is a wizard. His team is doing amazing things, and the tools they are providing are giving the teachers superpowers.”

Jonathon Guertin is the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) at Cajon Valley Union School District. A large whiteboard covers an entire wall of his office and is filled with all the goals his department is working towards. Jonathon’s experience is rare. He first started working in district IT as a student, ended up taking a job with a student information system vendor, and then circled back to education.

His ultimate goal? “Students need to be just as [aware] of their data as their teachers,” Jonathon shares. “I really feel like that’s going to help them as they become adults and start to make goals for themselves.” To date, in the absence of ubiquitous adoption of standards across the field, equipping students with the ability to see and own their data has been a challenging goal.

Superintendent Miyashiro compares the goal of having a full view of student performance to a personal health record: “We’re able to unlock DNA and genomes and really have precise information about each patient’s blood type, and their indicators that are showing different signs of concern for cancer or health. That type of information is available at the school level for learning. To give that power to the teachers and to the students to understand who they are and what they need… I don’t think we can even imagine what the positive impacts are going to be yet.”

Making full use of that data, though, is not easy.

Jonathon isn’t the only CTO tackling this work. Sharing data in a secure and accessible way is commonly shared challenge throughout education – whether a district is big or small, technology rich or poor, public or private.

Phil Hintz, the Director of Technology for the Gurnee School District 56 in Illinois, explains,

“We’re frustrated that we have a lot of good, longitudinal data from many years, but we don’t have a way of putting it all together in a packaged format that will inform our decisions so it can actually improve instruction.”

In a recent survey, some of the nation’s top Chief Technology Officers and data administrators in the League of Innovative Schools’ Data Interoperability cohort shared similar frustrations. Only 33 percent of districts reported that more than half of their teaching and learning tools are linked with their student information system.

The League is comprised of some of the most technically advanced districts in the nation, which begs the question: why is it so difficult to get our technology systems to share data to best equip our educators?

It all stems back to the lack of data interoperability. Megan Cicconi, the Executive Director of Instructional and Innovative Leadership at the Fox Chapel Area School District in Pittsburgh, states, “Something we’ve been talking about for years is this idea that our systems can talk to each other, and they can do so effortlessly without additional cost to our district… so we don’t have to upload CSV files or email [files] or hire a programmer.”

What does data interoperability look like? Take the airline industry as an example. Common codes and standards keep air traffic safe and controlled. Flight data is shared in the same format across nearly every airline, so a traveller can do a simple query online to filter flights by price, duration, and time, accessing thousands of data points across multiple vendors in seconds.

Compare that to the education industry. A teacher can’t even do the most basic type of query, like how a student is performing in math. Instead, she/he has to open multiple applications, each with their own way of displaying data, and try to derive meaning from different dashboards.

Imagine if every airline used different codes for flight patterns and someone had to copy and paste information from a spreadsheet before the air traffic controller could read it.

That is what the lack of data interoperability looks like in education.

The more tools a teacher uses in her or his classroom, the more overwhelming this universe of ever-growing data becomes to manage. There is data for student benchmarks, grades, behavior, learning objectives and more, and if every single application stores that information in a different format, it can’t be easily analyzed against, compared with, or integrated into another system.

Matthew Gaven, Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum, Instruction, Assessment, & Technology in Mineola Public School District in Long Island, New York, also would like to see a student dashboard of data some day, and argues that one of the biggest hurdles in creating that unified system is coming from the supply side. He says, “When you talk to different vendors… it’s not in their interest right now to make their system compatible with someone else.”

This lack of data sharing between systems is so prevalent that 100 percent of respondents to the aforementioned survey said their districts have dedicated staff for data management. These staff members are uploading and downloading data, writing scripts, manipulating spreadsheets, and literally copying and pasting information between programs.

The ultimate goal of data interoperability is to equip educators, parents and students with a full view of student progress so that educators can give the support needed in real-time, creating a more transparent data driven environment.

However there are three challenges that must be addressed in order to realize the benefits of fully interoperable systems:

School districts are often overwhelmed by managing the universe of data collected in the ever-increasing number of tools leveraged by their teachers in compliance with regulations from the federal to district level. Commitments such as the Project Unicorn Pledge (more in the next section) and the Student Privacy Pledge have helped increase transparency of the actions education technology vendors are taking to ensure the protection of student data. Ultimately, however, the security and privacy of student data is the responsibility of the school district. Local policies and national laws, like the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), impact the technology choices districts make.

Complying with regulations and policies is a huge component of school governance, explains Matthew Gaven from Mineola Public Schools. He says, “Each of the states seem to have different laws and different policies – and those policies filter down to local education agents. … We have to constantly work with the board and with our school attorneys to make sure our practices match our policies.”

In addition to ensuring regulations and policies are upheld, Matthew raises the ethical concerns that come with safeguarding student data: “We have to remember at the end of the day, all of this information is about somebody’s child.”

Megan from Fox Chapel Area School District agrees, saying, “We have so much information on these little humans that we are responsible for and we should be accountable just like banks and large corporations are held accountable.” But in order for systems to maintain security, they must be interoperable.

Getting systems to talk to each other goes a lot further than just managing rostering and single sign-on. There is data for assessments, learning objectives, local education standards, grades, behaviors, food service enrollment, language proficiency, extracurricular activities, parent and guardian information… and the list goes on.

Integrating all of this data is difficult, especially when each of these applications stores that data in different formats.

For districts like Cajon Valley, that has meant undergoing the painstaking process of writing custom integrations, or manipulating the format of data to ensure it moves smoothly between systems.

Sometimes the type of data stored is different between systems. A student’s grade level is an example: some systems may store the grade level numerically (grade = 9) while others might store it with alpha characters (grade = nine).

Other times, the data model is different. A student’s name is an example: some systems will request first name and last name in separate fields, and others may request the full name in a single field.

Jonathon at Cajon Valley is in a fortunate position to be able to tackle this challenge with his team. Rather than copying and pasting data in spreadsheets, they are writing code to automate some of those manipulations. Not all of these manipulations are complex; combining first and last name requires a simple addition function, for example.

However, when you multiply this problem by the amount of digital tools being used in a classroom, it quickly becomes clear why data transfer is such a challenge in districts.

Because of the scale of this problem, Jonathon warns that custom integrations are not a foolproof solution: “When districts are being asked to write 15-20 different integrations, it leaves a lot of room for error. Not only on our side but even from the vendor’s perspective where they’re writing interfaces for 40-50 different applications.”

A more comprehensive and accessible option, shares Jonathon, is to adopt shared data standards and push vendors to do the same. Many industries already have well-established standards.

The open standards for the internet have been defined through the Internet Engineering Task Force since 1986. Email standards are fairly recognizable; there is an address field (name@domain), CC and BCC fields, a subject, a body, etc. The airline industry, as shared earlier, has tackled this issue. The development of international standards and practices in the airline industry is governed by the International Civil Aviation Organization, which was was formed in 1947.

The internet and airline standards were first developed decades ago, but shared and open standards in education are still relatively new. In 2009 the federal government created the Common Education Data Standards or CEDS, this is a reference model that was then build upon by two standards organizations in order to put the model into practice; The Ed-Fi Alliance and IMS Global.

Organized in 2012, the Ed-Fi Alliance is a community of educators and technologists working to advance the principles of interoperability through the Ed-Fi Data Standard, which is a widely-adopted CEDS-aligned data model that governs and organizes data in a common language so that student information can be exchanged seamless between applications. IMS Global is another standards group that has developed specifications for curriculum and rostering, including their OneRoster solution, which can deliver rostering information to applications.

Despite the newness of educational data standards, many school districts are racing as quickly as they can towards unified systems.

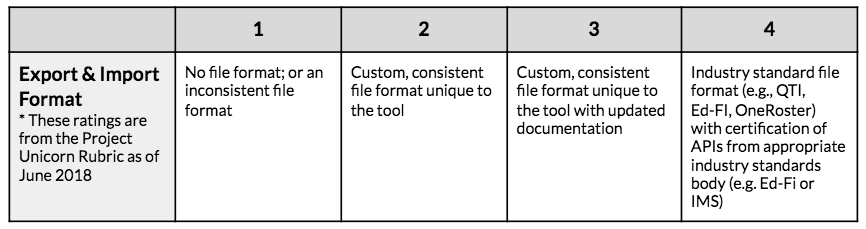

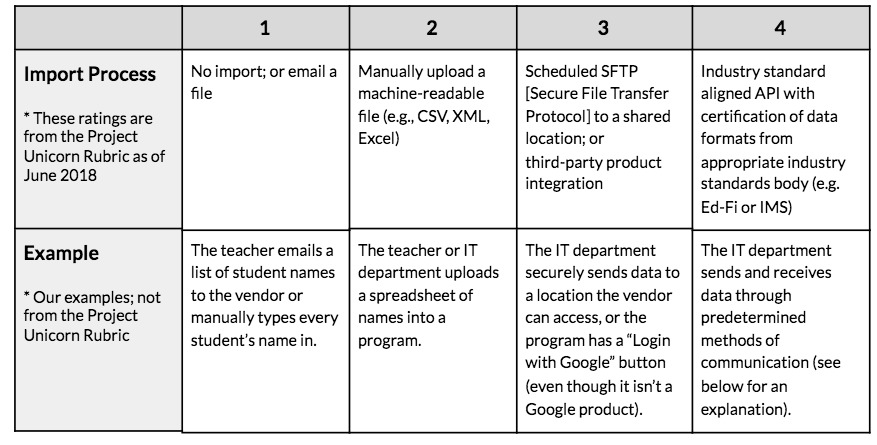

The Project Unicorn Rubric includes ratings for export and import formats for student data. The highest rating goes to vendors who use shared industry standards.

The Ed-Fi Data Standard is emerging as the standard of record as districts focus on how to adapt systems and tools to address interoperability. Ed-Fi defines a shared and open data standard for most education-related data like attendance, grades, classes, etc. At the time this was written, the Ed-Fi Data Handbook included structures for 599 different types of common data shared within school systems.

Adopting shared data standards doesn’t just benefit districts; it also helps vendors. Jonathon at Cajon Valley explains, “Vendors only have to create one integration. It makes it easier for the district. It makes it easier for the vendor. I would rather their focus be on instruction, improving education, and improving the tools that our students and teachers use instead of worrying about how data is going to sync with a student information system.”

Gurnee School District 56 has been a one-to-one iPad district for six years. Phil Hintz is also exploring solutions for an SSO portal for students.

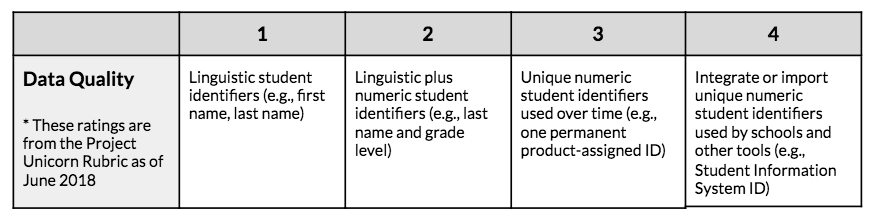

In addition to supporting ease of logging in, his goal for implementing an SSO portal is to ensure the security and privacy of student data being shared. Phil says, “A lot of [education vendors] want us to just upload CSV files with all kinds of information. … We’d love it to be as simple as a student ID number and that’s it. We have a unique identifier and that should be all that is required…at least from the school district standpoint. It’s been kind of a push-push situation.”

For a lot of districts, data interoperability is a journey. While there are serious benefits to the full adoption of a data standard, often the process takes a bit longer. There are still ways to advance student privacy in specific contexts, and organizations and resources that have identified ways to build out personal roadmaps.

Project Unicorn is an educational advocacy initiative dedicated to the secure, controlled interchange of data that helps provide resources to districts in helping them advance their data interoperability work, without endorsing a specific standard.

One of its resources is the Project Unicorn Rubric that can be used to evaluate a vendor’s support of secure data interoperability in their products, on a variety of factors.

One identifier in the rubric evaluates the import process for student rostering information — how a school adds a class of students into an application, which correlates to the level of security around this data. Vendors who score a higher rating have better privacy, efficiency, and accuracy of student data.

The highest rated suggestion, with a score of 4, would require students to be added to an application using a unique student identifier used by the school, like Phil suggests. This unique student ID might be a random string of letters and numbers that could be generated by the Student Information System (SIS) used by the district.

The reason for using a unique and anonymous student identifier would be to ensure the student could not be personally identifiable by an outside party, including the vendor.

The format of student data being shared isn’t the only concern. How that data is being sent to the vendor can also be a security challenge. Since manual data entry and upload is still so common, another identifier in the Project Unicorn Rubric focuses on better data import processes.

The most secure and efficient option in the rubric is for a vendor to implement a standards-based API, which stands for “Application Programming Interface.” An API is a structured way to send and receive information through predefined methods of communication.

With an API, data is communicated in an understood standard format which means that districts and vendors are not constantly investing in developing custom formats to enable and support data exchange. As a result, districts and vendors can more easily ingest and export data with APIs. Plus, APIs support dynamic, real-time data transfer and communications, thereby creating opportunities for teachers and students to access data and reports more readily.

For those education technology companies that want to improve their data transfer process, organizations like Ed-Fi and IMS Global Learning Consortium are supporting that shift.

Beyond creating systems that promote secure and private exchange of data, and delivering on the promise of privacy to students, a lack of interoperability is incredibly time consuming, and a drain on districts who simply don’t have the resources to address the problem. Adding a class of students into a new program may seem like a simple task, but it becomes a massive headache when each vendor expects that data in a different format.

As Jonathon says, “The hardest thing about doing anything is getting people signed in. A lot of the different applications have different ways to log-in. This app, it’s their ID number; this [other] one is their email address. I had people whose full-time job was just to enter people’s names into systems. How much time are we wasting to just get kids logged in?”

Cajon Valley Union School District implemented a single sign-on (SSO) portal starting in the 2017-2018 school year. Single sign-on is a process that permits a user to use one set of login credentials to access multiple applications.

Using SSO is like using a card reader for the security system across a building; not everyone has access to the same doors. Once a key card has been programmed, the carrier need only swipe to gain entry. Not only is this a lot easier to manage, but it’s also a lot safer because key cards can be reprogrammed or deactivated instantly by the administrator.

Now, every student only needs to login once to access a portal of different programs. For Principal Jacobo and her team, the difference was remarkable.

For Jonathon, the introduction of a single sign-on (SSO) student portal involved years of work integrating systems. It also required research into which SSO solutions were supported by the vendors they were already using.

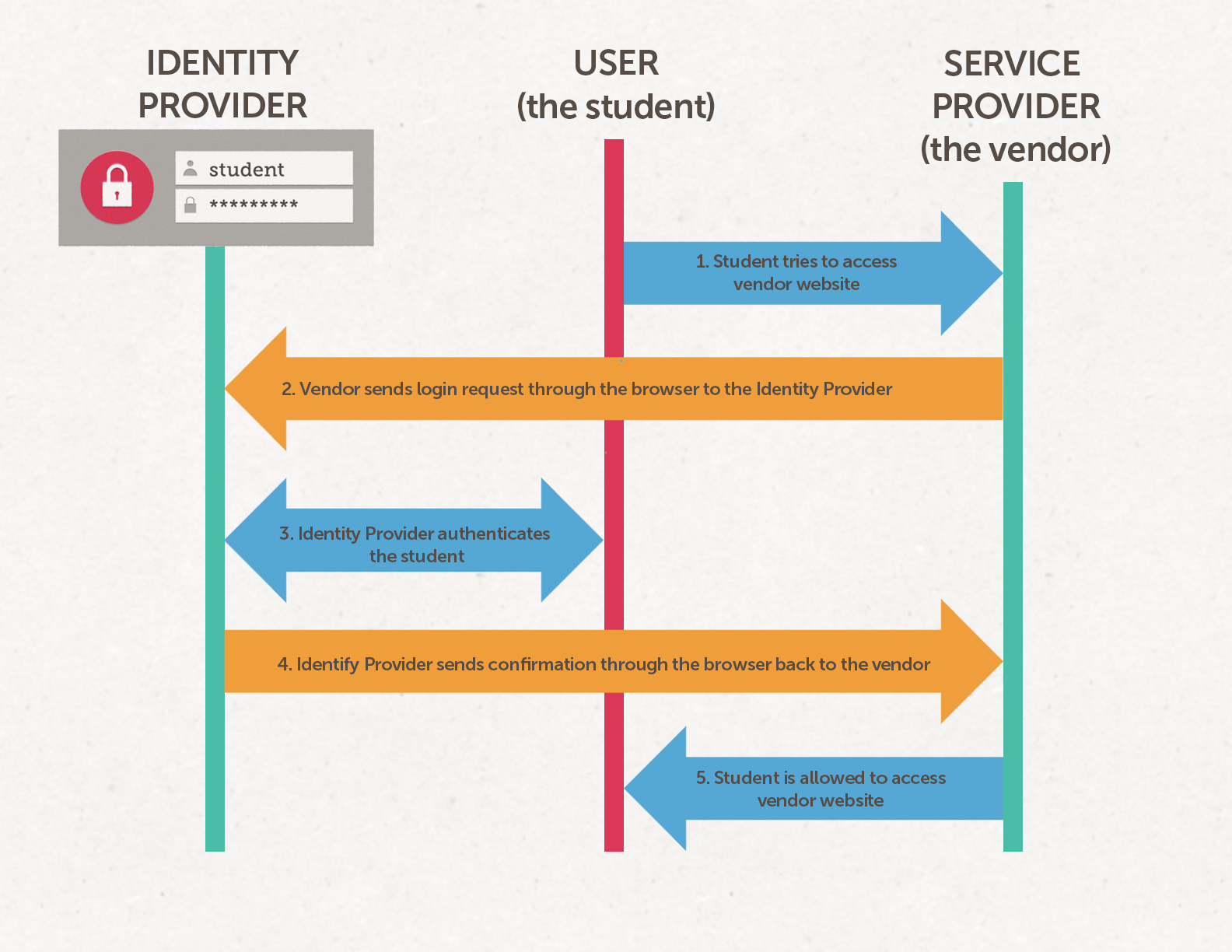

Here’s how SSO works.

The three participants in a SSO solution are:

The identity provider is a separate organization that offers user authentication as a service. Some examples are OneLogin, Okta, and Clever. These identity providers act as the intermediaries between the districts and vendors. That way, when a student authenticates with the identity provider, the vendor recognizes that authentication.

SAML, which stands for Security Assertion Markup Language, is an open standard for exchanging authentication and authorization data between identity providers and service providers. There are essentially five steps to using the SAML standard:

To make this work, the vendors must integrate with the Identity Provider selected by the district; but, some vendors don’t do this.

For Cajon Valley, the implementation of SSO has made the district more wary of purchasing tools that aren’t working towards better data interoperability. Jonathon explains, “Before we procure any application, it has to meet a set of standards. I don’t really purchase anything that doesn’t integrate with our system because the expectation of teachers is that they don’t have time to enter kids’ names into eight different applications.”

SSO has become a key requirement. Cajon Valley has refused vendors and applications because of their lack of compatibility with the Identity Provider they are using. Jonathon explains that a tool that requires individual data extractions for rostering or login – those that don’t include interoperability standards in their technical roadmap – aren’t effective tools for his district– and many other League of Innovative Schools members agree.

Eighty-eight percent of respondents in the State of Data Interoperability in Public Education survey said data interoperability has had an impact on decision-making or has been a primary consideration in district-level purchasing of an edtech tool.

Technology providers are just now coming onboard to the concepts and approaches of interoperability. School districts need to request and require interoperability and standards in the procurement phase in order to incentivize the provider to continue to move in this direction. There are a number of resources from standards organizations available to districts to facilitate these conversations.

Both the Ed-Fi Alliance and IMS Global recognize that technology providers must be part of the solution towards interoperability in order to equip school districts with the information they need. Information on how to work with vendors and the benefits of interoperability can be found at www.ed-fi.org.

Included in the IMS Global website is a set of resources school districts can use to ensure better interoperability when procuring applications. These resources include a sample Request for Proposal (RFP) language, types of questions to ask when talking to a vendor, examples of district procurement processes, and suggested requirements for vendor contracts.

Back at Bostonia Language Academy, students break from their daily schedule to take a school-wide picture. In the type of orderly chaos that only an elementary school can achieve, they gather on the field. Teachers and parent volunteers flank the sides.

The photographer climbs a tall ladder and begins to shout instructions in English. After a short pause, he grins, and then switches his commands to Spanish. The students cheer enthusiastically.

It is in this moment that the magic of this school becomes clear. At Bostonia Language Academy, the focus on languages is more than a school theme; it is the foundation of their community, where relationships are built through inclusive communication.

That focus on relationships is everything, explains Superintendent Miyashiro. According to him, technology is “a waste of time if we don’t have the interoperability because teachers aren’t going to do it. Anyone who’s been a teacher in a classroom knows that time is fleeting. And you have very little time to do anything else but build relationships, connect with kids, and get the learning going.”

Jonathon measures the technical progress Cajon Valley has made with a broader concern, saying, “I think we’ve been lucky to have that forward thinking about how data and systems should work together, because I think there are a lot of smaller districts out there that don’t have those resources and don’t have the technical ability to build some of this stuff. ”

But to solve data interoperability at scale will require more than just larger districts with the technical ability, Jonathon shares. It will require collaboration between districts and vendors.

Principal Jacobo agrees and thinks the companies that are flexible, adaptable, and attuned to what the district needs, including the integration of these interoperability standards, will be the ones that survive. She says, “Very quickly, we can tell who the people are that we want to work with.”

According to Principal Jacobo, these vendors are the ones that ask questions like, “How would you like to see your data collected? What types of reports are you looking for?”

For Megan at Fox Chapel, that collaboration will happen faster if larger districts apply pressure. She says, “If small districts…can’t afford to hire a tech person…who can program in that capacity, they’re at a loss. So if we…all joined together and say, ‘this is what’s best for kids: to have their data secure and to have instructional time utilized as it should be,’ then we can, together, demand that it changes. And I think there are a lot of larger school districts that are going to help us lead the charge for that because they’re customers.”

The way to make data interoperability in education a reality, is to join forces. Districts like Cajon Valley Union School District and the members of the Digital Promise League of Innovative Schools are committed to advancing data interoperability in order to realize the promise of technology to improve learning.

Here are some ways you can support data interoperability in your district.

Gain Fluency. Data interoperability is a challenging concept to understand. Familiarize yourself with some of the basics and help inform others as to the state of data interoperability in public education. There are also well-documented examples and case studies you can read. In addition, explore resources from Project Unicorn, an initiative dedicated to improving data interoperability.

Adopt Standards. Two organizations leading the way for the standardization of data interoperability are:

Demand Interoperability in the Procurement Stage.

Ask the right questions and create contracts with vendors that ensure they are working towards better data interoperability.

Join the Community.

Connect with like-minded people and commit to move data interoperability forward in education at large. Here are two organizations you can ally with:

Become an Advocate.

All great movements start with a shared language and understanding. Demystify the subject by sharing this case study and these resources with your school board and edtech purchasing department, or anyone tasked with procurement in your district.

Join the Digital Promise League of Innovative Schools in the movement to advance data interoperability in education.

This report was made possible by the support of the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation.