June 13, 2017 | By Aubrey Francisco and Bart Epstein

“What works ought to drive what we put in front of our children.” – Jim Shelton

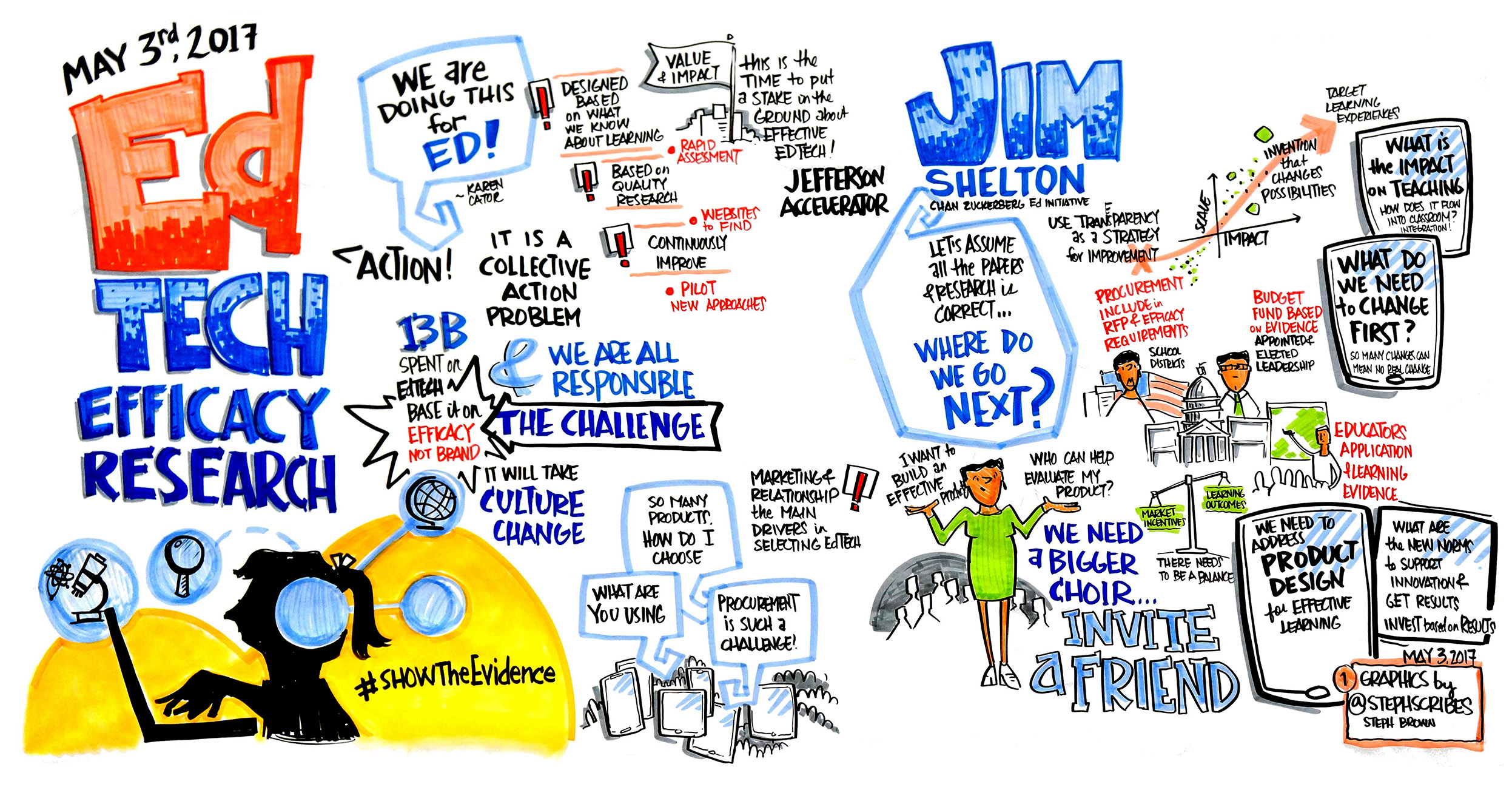

Motivated by this shared belief, more than 275 higher education and K-12 district leaders, researchers, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, investors, policymakers, and educators gathered on May 3rd and 4th in Washington, D.C. to address an essential question: How might we collaborate to ensure evidence of impact, not marketing or popularity, drives edtech adoption and implementation?

Over two days, more than 55 presenters shared their research findings and ideas for addressing this complex challenge. In action sessions, participants developed next steps for moving the work forward. Below, we share some highlights from the discussion.

Although over $13 billion is spent on edtech each year, many of the decisions on which products to purchase, implement, and scale are not based on evidence. In a survey of 515 school and district leaders responsible for making edtech adoption decisions, one Symposium working group found that 11 percent of decision-makers demand peer-reviewed research, 41 percent strongly consider research, and the other half either pay lip service to the importance of research or admit that research plays no role in their decision-making. And while Symposium participants agreed this is a problem “someone” should address, it is clear that doing so will require many stakeholders working together to create systems level change. As Robert Pianta, Dean of the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia, noted during his opening remarks, “There is no reason to expect the market will develop itself in a way to reward what we care about if we don’t come together and take action.”

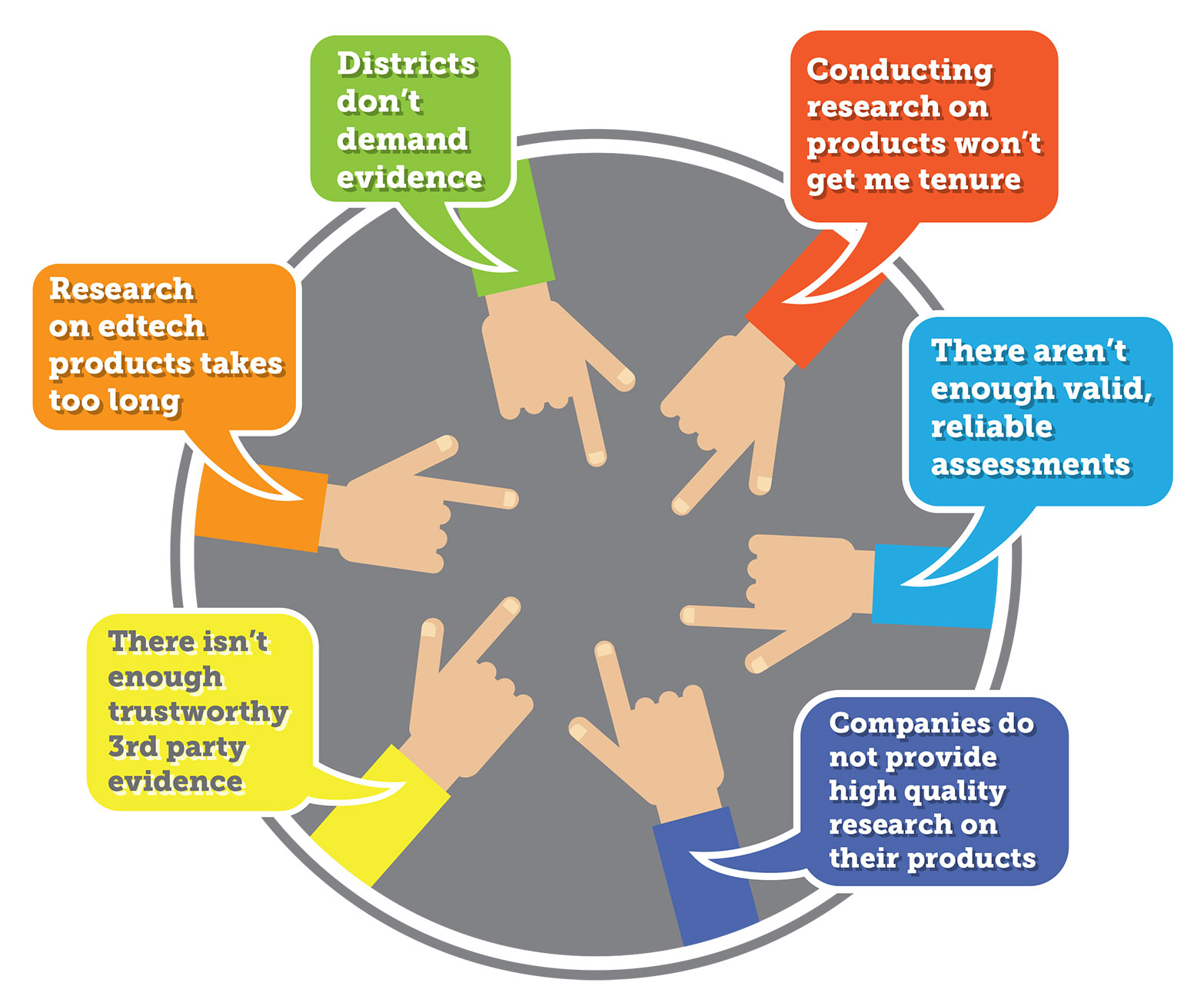

On Day 1, presenters shared findings from 10 working groups who collaboratively worked over the previous school year to investigate barriers to increasing the role of efficacy research in edtech, and potential opportunities for addressing such challenges, such as the high cost of collecting, analyzing, and sharing data, and developing a sustainable, effective system for crowdsourcing research on edtech products. A common theme quickly surfaced from the working group’s findings: each stakeholder group in the edtech ecosystem – product developers, investors, researchers, universities, and K-12 districts – is behaving rationally based on current incentive structures.

For example, companies who do not invest significantly (or at all) in research say they don’t do so because their investors and customers (districts and IHEs) aren’t asking for it. In a recent survey, edtech providers reported districts most heavily rely on peer or consultant recommendations, end user recommendations, and non-rigorous evidence. Academic researchers, too, say they aren’t to blame, because conducting research on ed tech products doesn’t help them get tenure. And, districts leaders want to base their decisions on rigorous evidence but often do not, largely because it doesn’t exist, isn’t provided by a trustworthy third party, and/or the research wasn’t conducted in a setting relevant to their own the context.

In this way, the saying, “every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets,” applies to the systemic challenges that have resulted in limited use of evidence in edtech. And, if we keep doing what we have been doing, we should not expect this outcome to change. Progressing toward a system where evidence drives decision-making will require rethinking these incentive structures and moving from pointing at one another to individuals and organizations stepping up to take action.

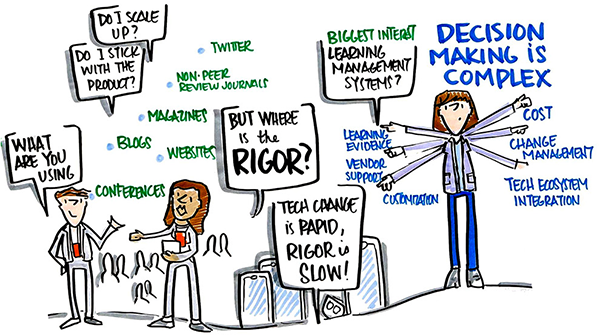

Armed with a better understanding of the barriers to evidence and stakeholder perspectives, participants spent Day 2 developing change ideas for addressing these challenges. In breakout groups, summit attendees tackled key questions such as: How might we ensure K-12 district and higher education technology decisions are based on evidence? How might we better crowdsource research and product reviews to support decision makers? How might we develop a mechanism for funding research on edtech products? Throughout the day, education leaders, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and researchers shared additional resources and strategies for addressing these big questions.

Across these presentations, discussions, and breakout group report outs, several common themes and potential next steps emerged.

Create a type of “Consumer Reports” for edtech. Busy educators desire information that can help them determine the likelihood a particular edtech tool will meet the needs of their teachers and students, fit with their IT environment and instructional philosophy, and meet their privacy standards. Individuals at districts and universities across the country are gathering data using both informal and formal methods as they select and implement edtech. Kyle Bowen, Director of Technology Services at Penn State, shared with one Symposium Working Group:

“The only way to truly understand the implication of a technology is to invest in it in some way… We have an emerging technologies group inside our organization, and their whole focus is on early evaluation. As tools are being launched and just coming onto the market, at that, point there is no research that exists in these spaces…That’s where we’ve developed our own ways of doing early evaluations on technologies to understand is it even viable as a technology.”

While IHEs and districts across the country are doing the same, they lack the time, incentives, and mechanism to document their findings. In a breakout discussion focused on crowdsourcing evidence, participants argued for stipends and support to help these leaders document their findings, which, along with data from other sources, could be analyzed to understand which products are being most successfully implemented in which environments.

Help decision makers determine “just-right” evidence that matches the purpose, risk, and scale of an edtech implementation. Symposium participants agreed that the type of evidence needed to inform a particular edtech decision varies significantly across settings, and depends on a number of factors, such as how much the product costs, how many students will use it, and how much professional development is required. Susan Fuhrman, President of Teachers College, Columbia University, noted, “Efficacy in the scientific world is defined as definitive outcome as the result of a random control trial. This does not suit what respondents are interested in.” While several taxonomies that define levels of evidence exist, such as the NSF Common Guidelines, ESSA, and the Learning Assembly Evaluation Taxonomy, there remains a need for common definitions for different types of research. Additionally, stakeholders need guidance on determining what level of evidence is necessary to move forward in implementing or scaling a particular tool.

Develop collaborative partnerships to generate more evidence on products across contexts and implementation conditions. Although much could be learned by crowdsourcing insights from those in the field, symposium participants agreed on the need for more research on edtech tools that is generated through rapid cycle evaluations. In lightning talks, presenters shared existing efforts to address this challenge, such as Mathematica’s Rapid Cycle Evaluation Coach and the Harvard Center for Education Policy Research Proving Ground project. Participants also discussed the potential value of partnerships between research organizations and existing regional and national networks, such as the Massachusetts Personalized Learning EdTech Consortium and the League of Innovative Schools. Coordinating and scaling these efforts will require new funding mechanisms to generate the research everyone agrees is needed.

Train school leaders, educators, and faculty in new pedagogical methods and in evidence-based decision making. Everyone agrees there is a need for “smart demand” from edtech consumers, including teachers, school and district leaders, faculty, and students. Tools designed to aid in evidence-based decision making, such as Digital Promise’s Ed Tech Pilot Framework and Mathematica’s understanding types of evidence guidelines, offer one approach to building capacity on the demand side. In addition to these types of in-service supports, schools of education must train teachers and education leaders to effectively implement technology for learning, including evidence-based decision making. Dr. Glen Bull, who led research for the group investigating institutional competence in evaluating edtech research, offered an immediate next step for getting started: facilitate communication between recent school of education grads, expert practitioners, edtech providers, and professional associations so that schools of education can develop more effective training programs.

The main takeaway from the summit: moving evidence to the center of the discussion regarding the development and implementation of edtech will take coordinated action from many stakeholder groups. As Dean Pianta put it in his opening remarks, “This is the time to put a stake in the ground to ensure that in the future, the products being developed now have a demonstrable effect on student learning.” To create that future, we must build a movement that includes a broader, more diverse set of voices from every stakeholder group. Jim Shelton noted that symposium attendees (and likely those reading this) are “the choir” – we each need to bring 10 people who don’t think they belong in this effort to this conversation and get to work creating systemic change.

Be a part of the movement – share your ideas for ensuring evidence drives edtech adoption and implementation!

Sign up for updates on future projects and events.

Tweet us at @digitalpromise @JEAUVA @UVACurry using the hashtag #showtheevidence

View the working group reports, presenter slides, and a list of participants. Learn more about working the groups on the event website.

By Lauren McMahon and Heather Dowd