While technological advancements in schools have provided incredible new opportunities to learn, there is a digital learning gap emerging in the U.S.

Affordable access to high-quality technology is still slow to reach many low-income communities, especially those in rural areas, where both economic and geographic factors are restricting. Nearly 40 percent of rural homes across the country have no Internet access, compared to 27 percent in urban homes, according to a recent U.S. Department of Commerce study.

These trends put rural schools at risk. Technology is crucial for conducting research, connecting with the world, and applying for colleges and careers. Though rural schools are typically viewed as a small fraction of the public education system, in reality one third of schools and one half of districts are considered “rural” by the National Center for Education Statistics. With funds scarce, this significant part of our public education system could fall even further behind.

At Piedmont City School District, in rural northeast Alabama, technology is viewed as a tool for raising expectations in a town hit by hard times. A once bustling town home to a thriving textile industry, two major employers have left in recent years and many local businesses shut their doors during the economic downturn.

About one in five Piedmont residents now live in public housing. Two of every three students in the district are eligible for free or reduced lunch. Many families cannot afford to keep the water running or the electricity on, let alone an Internet connection.

To restore hope in the community, the district is working to provide an education that prepares students for a modern global economy, rather than the one that departed the town over the past 15 years. Through its mPower Piedmont initiative, which began in 2009, all students in grades 4-12 receive a laptop with home Internet access. This is offered despite many ongoing challenges typical of rural districts like Piedmont: a limited and ever-changing budget, the area’s lack of broadband infrastructure, and a small staff, many of whom have multiple titles.

Because of the district’s circumstances, Matt Akin, the superintendent, doesn’t like calling mPower a “technology initiative” – that would put outsized focus on the laptops and software. Akin instead calls the effort a “community transformation initiative,” and while it could seem cliché elsewhere, the term appears apt when visiting Piedmont and talking to staff, students, and residents.

While there are still those in Piedmont who are skeptical of such major change, results have been promising: enrollment is up at the district, as is student achievement and college attendance, and college remediation for graduates is down.

“The laptop simply provides a means for our students in a rural area to access a wealth of knowledge they wouldn’t have otherwise,” says Akin, who has been superintendent in Piedmont for 10 years. “The fact that all of our students have access to a device and Internet access all the time, immediately we felt better about where we live and where our kids go to school.”

The roots of mPower Piedmont date back to 2000 when Akin was a first-year principal at Piedmont High School. Akin, who is from Hokes Bluff about 20 miles west of Piedmont, is a self-described “nerd,” who as a teen received a TRS-80 as a birthday present and later taught computer science.

As principal, he applied for and received a federal grant to provide laptops for 30 incoming freshmen that coped with issues ranging from learning disabilities to truancy, Akin recalls. The project, which lasted a year, left several lessons. Akin realized “it wasn’t so much about the technology, but about motivating and believing in these students.”

But it also illustrated the challenges of implementing technology in a rural district. The wired network in the high school classrooms was too slow and the school failed to train teachers adequately in how to use laptops to enhance learning. “We weren’t even sure what professional development to do,” Akin recalls.

Akin became superintendent in 2003, by which point the district had three to four computers in each classroom, nothing “earth-shattering,” he says. But the technology was useful for high school students to recover credits, a key obstacle to graduating for some. “I was able to see the potential impact for struggling kids – for whatever reason, school wasn’t working for them,” he recalls.

In 2009, the district took advantage of a federal Enhancing Education through Technology grant to buy 30 laptops, a laptop charging cart, and professional development for another pilot project at the high school. As Rena Seals, district technology director, recalls, by the second semester, demand for the laptops was so great that the district bought 90 more laptops for the high school with federal stimulus funds.

At the time, the district’s enrollment had for the first time dipped near 1,000 students, something of an unwanted milestone in similarly sized districts. The town lost its two largest employers not long before that, beginning with the 100-year-old Standard Coosa-Thatcher textile mill, which closed for good in 2001, and followed by Springs Global U.S. Inc., a textile factory that moved to Mexico six years later. In the past 20 years, Akin estimates about 4,000 jobs have left the town of roughly 5,000 residents.

Families were leaving Piedmont, in search of better opportunities. “We weren’t preparing our kids for the world outside of Piedmont,” Akin says.

In other words, the district wasn’t preparing students for living in a connected world. “In our area, we probably had more kids without technology in their homes than we did those with laptops, or even computers,” says Seals.

Providing that access, Akin says, was “a moment of opportunity.” He continues, “I have certainly felt that if we didn’t do anything else other than give every kid a laptop, we would have provided a great opportunity to kids because they wouldn’t have it otherwise.”

Soon after purchasing laptops for the district’s high school students, Akin and his small team were able to convince local officials to ante up funds for 640 additional laptops – with four years to pay, at zero interest. With students in grades 4-12 receiving their own device, mPower became possible.

The next step is what sets Piedmont apart from many districts, whether rural or not. For its students to receive a truly 21st-century education that is competitive with those around the country, the district knew technology access couldn’t end at school. First, the district decided to allow students to take laptops home during the school year. For many families, it was the first computer they owned.

But the district quickly realized that more than half of households also didn’t have Internet access. Students had to download homework before they left school for the day just to get work done. Akin recalls driving around town late at night and seeing the glow of laptops in front of the middle school building; students were sitting outside to connect to the wireless network.

“A fixed household income will only go so far. Internet access is just not possible for most in our community,” says Sandra Akin, the guidance counselor at Piedmont High School.

“A fixed household income will only go so far. Internet access is just not possible for most in our community,” says Sandra Akin, the guidance counselor at Piedmont High School.

In order to complete the access it believed students needed to thrive, the district established the infrastructure to provide all students with home Internet. Using fiber optic cable that had been attached to the utility poles in the town but never used, the district set out to create a “wireless mesh” to offer free internet access to all of its families. The network was built with $896,000 in funds from an E-Rate pilot program called Learning on the Go. As Seals explains, the district was the only of 20 grantees that chose the wireless mesh option, which used strategic locations within Piedmont’s irregular, Appalachian foothills topography as Internet hotspots.

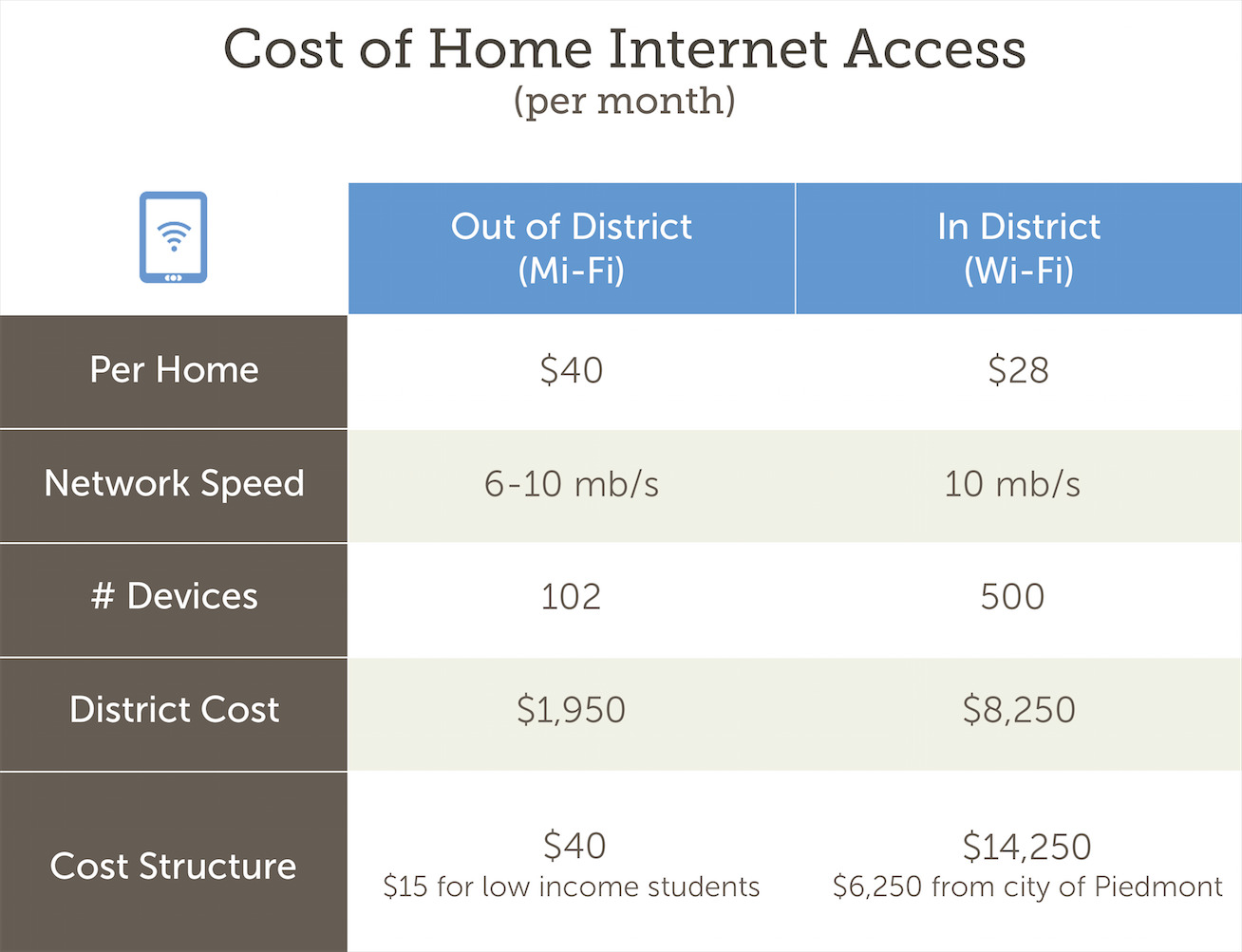

As a result, all students living within Piedmont limits received Internet, with the district and the municipal government covering the costs. For those outside the district limits, Piedmont worked with Verizon to provide MiFi hotspots, making access to high-speed broadband available first for free and then for $15 a month for low-income students.

With families able to access learning technology, many limitations typical to rural communities have been eased. All students can work on homework, collaborate on group projects, and interact with their teachers from home. Through the Piedmont Virtual Academy, the district offers online courses for foreign languages like Mandarin, Advanced Placement courses previously unavailable, and credit recovery for students who need to take more courses than can fit into the school schedule. At the middle school, 40 percent of students complete a self-paced online course over the summer.

At high school, students take first period online and can take the course from home if they maintain a B or better average. Each student meets regularly with a teacher-advisor to set academic goals and stay on track.

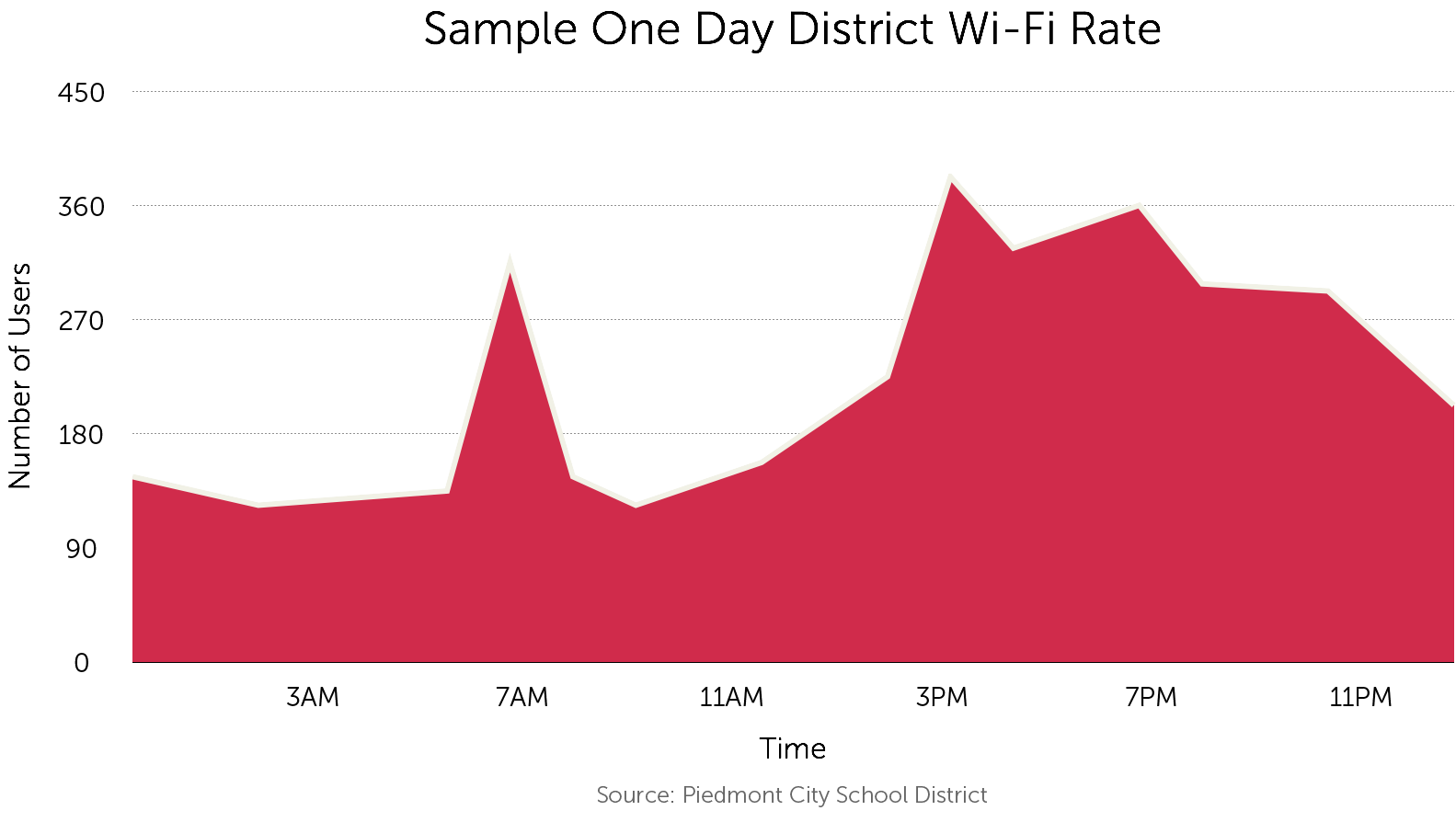

Even family members and parents of students have reported using the home access to apply for jobs and get information about the school district. Network usage data shows the biggest traffic spikes during out-of-school hours, with peak times at 7 a.m. and between 3 p.m. and 6 p.m.

The status of that network has been tenuous in recent years, with the district continuously seeking local, state, and federal funds to keep it running. Recently the district reached a funding agreement with local officials to continue to offer wireless access to homes, after several months of uncertainty. Relief may come soon in the form of a Federal Communications Commission initiative that will make $4.5 billion otherwise reserved for phone lines in rural areas available for high-speed broadband.

This, says Seals, is the biggest hurdle facing small, rural districts: “If you don’t have access 24/7, you lose a lot of opportunities.”

As a community transformation initiative, mPower’s focus is on changing expectations and providing hope in a town lacking opportunities. Those opportunities are perhaps best illustrated through 18-year-old Billy Martin Jr. As he himself puts it, he “was going down the wrong path” during his junior year of high school.

“When he was younger, the classroom didn’t suit Billy,” says Allan Mauldin, Martin’s U.S. history teacher. “Billy was kind of a loner. He was kind of that kid that wanted to sit in the back of the classroom and not really have any attention drawn to him.”

He fell behind in his classes and then left school altogether, thinking “I’m never gonna get this done,” he says. With some small-town support from his guidance counselor and principal, who often drove him to school, Billy decided to try and make up for his lost credits by taking extra courses online, outside the typical school day.

He started the 2013-14 school year a junior but was able to move ahead and graduate to senior status in the fall semester. In the spring he carried a full course load while also taking a make-up class of applied physics online. For Billy, a more independent learning experience proved a better fit.

He started the 2013-14 school year a junior but was able to move ahead and graduate to senior status in the fall semester. In the spring he carried a full course load while also taking a make-up class of applied physics online. For Billy, a more independent learning experience proved a better fit.

As long as his grades remained solid, he could take some of his classes at home, and meet with a teacher during an advisory period when he needed guidance. On one weekday night, Billy sat on his front porch going through an interactive science lesson online.

“You can learn at your own pace,” Billy says. “You don’t have to speed. You don’t have to hurry up, rush, and get everything wrong.”

Billy does not come from a family that would otherwise be able to afford a computer or Internet; the laptop Piedmont provides is his first. But he’s quickly taken to it. He’s writing short stories in his spare time and he’s expanded his love for video games into pursuing a video game design program with a friend.

“He’s learned maturity, he’s learned to be independent, he’s learned a lot of other life lessons from having the online course that I don’t know he would’ve got as well in just a face-to-face situation,” says Mauldin.

For Billy’s father, a tough mechanic who urged his son to pursue his education, these opportunities are a way for Billy Jr. to break away from a path that he feared he would not be able to avoid.

“I always wanted him to be better than me,” says Billy Sr., who says he dropped out of school early on. On May 22, 2014, just more than a year after Billy Jr. dropped out as a junior, he received his high school diploma.

“Billy’s a success story,” says Sandra Akin, who was Billy Jr.’s guidance counselor and is instrumental in connecting students with different learning opportunities. “He had so many ups and downs and so many times when he could have given up.”

In a small town like Piedmont, it isn’t hard to find similar stories of students and families turning to education to overcome their hardships. Courtney, a senior, was also able to make up credits online and graduate this year despite giving birth to a child during the school year.

In a small town like Piedmont, it isn’t hard to find similar stories of students and families turning to education to overcome their hardships. Courtney, a senior, was also able to make up credits online and graduate this year despite giving birth to a child during the school year.

Besides students, parents have benefited from the technology access. Monique Stitts, a single mother of three children, didn’t have computers at home until her sons brought them home from school. Since that moment four years ago, she’s used their laptops to find a job and track her kids’ grades online. Stitts hopes her children’s access to digital technology will allow them to “go further than I did” – including going to college.

Even for families that can afford Internet, the high-quality access goes a long way. Theresa Leighton’s family lives about 10 miles outside of Piedmont and paid a significant amount for Internet at speeds too slow to stream video. When her three children switched to Piedmont, the family could access Internet through the Verizon cards, getting faster speeds at a fraction of the cost. Leighton has gone back to school herself, studying at nearby Gadsden State Community College and taking courses online.

In school, mPower is significantly impacting teaching and learning at the district’s three schools, from freeing up time for a 2nd-grade teacher to work with individual students, to helping high school students recover credits to graduate on time.

During a visit to a 2nd-grade classroom, some students worked on iPads using software that caters curriculum to their skill level. Another group worked on a project on laptops and a third sat in a semicircle with the teacher for a lesson about telling time. In these environments the teacher decides what skills are best to develop for each student and can use technology to deliver those lessons, while spending one-on-one time with students who need it most.

Down the hall, a 3rd-grade classroom was divided into groups of three and four students, some of whom sat on the floor. Each group listened to different songs, trying to pick out similes and metaphors. Outside the classroom, on the wallspace normally devoted to essays or drawings, a series of QR codes led smartphone users to watch videos created by students. Between February and May, K-2 Piedmont students in blended learning environments showed academic growth of 0.29 grade levels in reading and math, based on data from Global Scholars Scantron Test, well exceeding expected growth rates. After school, 4th and 5th graders are among the 2,500 nationwide involved in Google’s Computer Science First curriculum that helps teachers support students in learning to code.

At the middle school, it becomes clear how Piedmont is using technology as a tool for career-readiness. In a robotics class, a group of 8th-graders worked in pairs to create robots with Lego pieces. Two boys watched as a small car changed direction based on how they programmed the device’s motion sensors. A pair of girls showed visitors a video they made explaining their idea for a robotic device remotely programmed to sort recyclable materials.

Bigger changes are underway at Piedmont Middle. After receiving a Next Generation Learning Challenges grant, the school adopted a new competency-based approach to learning. Students progress based on mastery of skills rather than seat-time and use learning technology to move at their own pace. They set their own individual goals and work with teacher mentors to pursue them, with a flexible schedule that caters to project-based and independent learning.

The competency-based approach, the robotics class, the project-based learning – it is all a response to the shift from a workforce that values what you do over what you know.

“It’s very important that kids have hope,” says Mauldin. “And by knowing that there’s this digital world out there, by knowing that ‘I can do anything through the technology, that I can show my creativity through it, I can learn anything through it, I can do whatever I want to do through it.’ That gives them that hope.”

Piedmont is fortunate to have teachers that, for the most part, bought in to mPower. Before the initiative launched in 2010, more than 80 percent of the district’s teachers took time from their summer vacations to attend a conference in Mooresville Graded School District, North Carolina, which a few years earlier began a 1:1 laptop initiative that became a model for Piedmont and many other school districts.

Teachers at Piedmont are vocal about both the successes and challenges of teaching in the digital age. At a meeting of several teachers from different grade levels, a few younger teachers note that schools of education do not teach how to use technology for instruction. One younger teacher says she still gets a little frustrated with some of her older colleagues, who are “used to doing things a certain way” and have difficulty incorporating computers into their classrooms.

Teachers at Piedmont are vocal about both the successes and challenges of teaching in the digital age. At a meeting of several teachers from different grade levels, a few younger teachers note that schools of education do not teach how to use technology for instruction. One younger teacher says she still gets a little frustrated with some of her older colleagues, who are “used to doing things a certain way” and have difficulty incorporating computers into their classrooms.

Another lands on a theme with which all seem to agree: “The biggest change has been in the pedagogy.” A 5th-grade science teacher describes, as her colleagues nod in agreement, the evolution of her own style since mPower began.

“At first,” she says, “we thought we were really using technology, but we were just scanning handouts.” A colleague across the table jumps in: “We had a light-bulb moment – we realized we were not pushing the edges. We just knew we could do better.”

For Stephanie Steward, a middle school math teacher that is now a blended learning coach, that means letting students “go learn on their own, rather than depending on a teacher for the information.“

Mauldin, the U.S. history teacher, takes that a step further.

“I look at myself as a life coach as well as a facilitator,” he says. “I have to tell them, ‘You’re going to learn the time management skills, the ‘get it done’ aspect of life that you have to have to be successful.’”

For teachers that have succeeded in the past, this can be a particularly difficult adjustment.

“You have to accept that being a facilitator and not the teacher on stage is not a demotion,” says Rachel Smith, who is curriculum coordinator for the district.

“You have to accept that being a facilitator and not the teacher on stage is not a demotion,” says Rachel Smith, who is curriculum coordinator for the district.

One high school social studies teacher says the biggest adjustment she’s made to enhance student learning is de-emphasizing the sheer acquisition of information, which she believes is an unneeded focus brought on by high-stakes standardized testing.

“If I teach them to be good problem solvers, critical thinkers, analytical writers, it will work itself out,” the teacher says. “I’m past the idea of me teaching stuff and them writing stuff down and answering questions. I’m past facts. They can Google facts.”

Before launching mPower, Piedmont performed relatively well on traditional academic metrics like graduation rates and state exams and it still does. But the district is less interested in those traditional metrics, instead evaluating whether students are more engaged with school and prepared for the world that awaits them.

Before the project’s start, the district’s composite scores on ACT, the college-readiness test, were about a point below the state average. Since then, those scores have matched or risen slightly above state scores. But more importantly, 70 percent of students are taking the test, as opposed to just 30 percent prior to mPower. In 2014-15, 95 percent of Piedmont students graduated, putting it in the top 5 percent in the state.

Data suggests students are performing better once they leave Piedmont. Alabama tracks the percentage of students that need remedial help with English and math when they reach college. In 2010, the year mPower started, 38 percent of graduates needed remediation. It is now about 24 percent, more than five points below the state average.

Piedmont is part of the the Collaborative Regional Education (CORE). Through CORE, Piedmont, nearby Jacksonville State University, and 20 other regional school districts are sharing best practices and professional development in learning technology to create a pipeline of students engaged in 21st century learning. With JSU, Piedmont offers a year-round student teaching program immersed in blended learning. Read more

And enrollment has increased to 1,240 students, a 20-year high and 20 percent increase from the low point that preceded mPower. Piedmont is an open enrollment district, which means students from outside the district boundaries can enroll there; it’s seen an influx of out-of-district students in recent years.

“Piedmont could easily be just another one-red-light town that lost everything,” says Mauldin, the U.S. history teacher. “What this technology initiative has done for our town is it’s brought more interest into the schools. It’s brought people into the community, and hopefully at some point in time, it will help to attract some industry back to Piedmont.”

Christopher Ray, a student at Piedmont High, begged his parents to send him to the district so he could attend a technologically savvy school that offered the courses and extracurricular activities that interest him.

“Ever since I went to Piedmont, I’ve just grown towards technology,” he says. “Since I started taking a computer science class, I was like, ‘You know, this would be a good job to take, a good field to go into.'”

As a result of this success, the district is emerging as a model for 21st-century rural education in the U.S. Piedmont High has been ranked the second-most connected school nationally by U.S. News & World Report, and was recognized by Apple Inc. as an Apple Distinguished School – one of 56 in the nation and the only Alabama.

In a small town like Piedmont, residents look to the community’s to indicate whether an initiative is having its intended impact. This is especially true of parents, who are creating new goals for their children.

“I would like for her to go to college,” says Eursula Houston, whose daughter Kayden is a top student at Piedmont Middle. “Anything is possible. She could be president if she chooses to be. She can go as far as she wants.”

Above all else it’s because of that attitude that Akin calls mPower a “community transformation initiative.”

“As you lose jobs and you lose people, it just becomes natural to think, ‘Well, that’s how it’s always going to be,’” Akin says. “You lose that feel of, ‘We just have to fight through this.’ One of the things we try to focus on is redeveloping those skills within our kids.”

Text:

Digital PromiseVideo:

Digital PromisePhotography:

Digital Promise

Courtesy of Piedmont City School DistrictFor all media inquiries,

please contact Erica Lawton, Communications Manager.