October 23, 2014 | By Digital Promise

Despite remaining questions on the applicability of this research to education, “brain-based learning” curricula and products are ubiquitous, and many are built on scientifically inaccurate information. Therefore, it is critical that science and its practical implications for education be integrated and clearly articulated for teachers and school leaders if it is to meet its potential to positively inform educational practice.

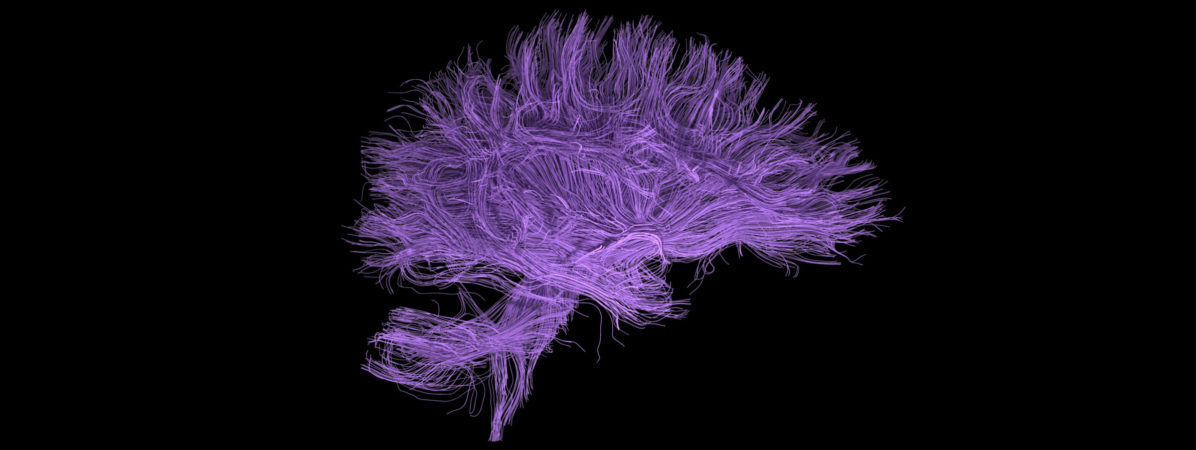

The field of Mind, Brain and Education was developed so scientists, policy-makers and educators could more responsibly integrate findings in biology, psychology and cognitive science into educational practice. This young field has the potential to “use research tools, such as brain imaging, analysis of cognitive processing and learning, and genetics assessment to illuminate the ‘black box’ and uncover underlying learning mechanisms and causal relations” (Hinton & Fischer 2008). In this interview, we asked David Daniel, managing editor of the journal Mind, Brain and Education and winner of the 2013 Transforming Education through Neuroscience Award, about this emerging field and its relevance to teaching and learning.

Mind, Brain and Education is an transdisciplinary field seeking to:

As technology evolves to allow meaningful investigation of biological processes, neuroscience and genetics, for example, MBE developed to pull together a plethora of potentially helpful findings across diverse fields and to focus those efforts on one of the most transformational cultural experiences: education.

It would be a big mistake to view educational neuroscience and MBE as entirely synonymous. Educational neuroscience is only a part of MBE. While neuroscience is certainly an important aspect of MBE, it is but one of many potentially promising areas and levels-of-analyses that converge on educational practice, policy and related scientific inquiry, all of which dynamically interact in the typical classroom.

Very few scientific findings have been carefully tested by teachers for normal classroom use. One way teachers can contribute to the field is to carefully design and adapt the more promising findings for use in the “real world,” using methods that allow us to document and evidence their efforts. To do this, however, teachers and scientists must agree upon what “proof” is and share a vocabulary that encourages true communication. Another way teachers can participate in MBE is to furnish relevant questions from their perspective for scientists to investigate. If scientists do not ask questions relevant to educators, their findings may be very difficult to leverage in teaching and learning contexts.

Scientists are experts in the scientific process as it applies to a particular area of study. They are not experts in teaching, and should not be expected to be.

To maximize potential impact of scientific findings to educational practice, teachers, being the experts of their context, can contribute testable questions that yield themselves to the scientific method.

For example, “How are kids different” is not a testable question. However, if teachers were to put forth a theory of how different identifiable groups can be best educated based upon their accumulated classroom experience, scientists can help test that proposal, and maybe even assist in the theoretical explanation for why it may, or may not, have been supported based upon related scientific findings. Teachers can refrain from looking to scientists who are not asking questions from an educator’s perspective and begin formulating the questions themselves. Many scientists would, and do, welcome this sort of collaboration.

The term “brain-based” is primarily a marketing tool. Teaching is a practical pursuit. As an educator, I don’t think it matters so much what certain techniques are “based” upon. It matters more if they actually work. I would urge educators to seek pedagogical strategies and curricula that have been demonstrated to show evidence and promise in representative contexts like classrooms, rather than being seduced by tantalizing arguments.

What research questions do you have related to mind, brain, and education? Tell us in the comments below!

By Andrew Vollavanh and Sierra Noakes