Children entering the education system are doing so at a time of significant change. In most states, kindergarten students are among the first cohorts to be fully immersed in a new set of national academic standards. These same children are also wholly of the digital age, arriving to the classroom with an entirely new set of information-gathering habits and technological expectations.

At Utica Community Schools, a school district in Macomb County, just outside Detroit, these changes are apparent. UCS is in the heart of the auto industry, which is facing an important transition from traditional manufacturing to a need for knowledge of high-tech systems. Students entering the district will have a very different academic and post-graduate environment awaiting them than previous generations.

In 2011, a confluence of financial, legislative, and cultural factors provided UCS an opportunity to address the transforming educational and economic landscape. On the heels of a successful bond issue that included technology funds, state efforts to incentivize full-day kindergarten, and widespread anticipation of the fast-approaching Common Core State Standards, UCS decided to modernize how and what its students learn, beginning with their first day in the district. Starting in kindergarten, UCS now offers students an education that meets a new set of expectations, and is facilitated by teachers who can better personalize education for each student.

In the classroom, students use a “blended learning model,” progressing through different “centers” based on a plan determined by the teacher using adaptive software. Students can work on tablets or laptops at their own pace, collaborate with peers in small groups, and receive targeted face-to-face instruction with teachers who have become orchestrators of individualized learning.

Despite some growing pains, there are signs that early in the second year of a full-day, blended model at UCS, students, faculty, and families are embracing the new approach. Students are mastering concepts at an increased rate, teachers are becoming confident in the restructured program, and entrepreneurs are adapting to the needs of the district. This year, the district expanded the program for first graders and is currently exploring future growth.

UCS can credit the successes to intensive professional development, unique relationships with technology providers, and an efficient use of resources. But in 2011, with a launch date of August 2012 and only an inkling of how it would enact these changes, UCS needed to figure out what it would take to get there.

Before 2011, Michigan school districts received full per-pupil funding for kindergarten students, even if they only attended school for half the day. Motivated by early childhood research touting the benefits of full-day kindergarten, the state legislature changed the formula so that school districts would have to educate kindergarteners for a full day to receive the corresponding funding.

At the time, only 36 of 83 UCS kindergarten classes were offered full-day. The funding change made the switch to full-day kindergarten worthwhile. But the district looked a step further: what if it not only expanded access to kindergarten, but reimagined how those students learn?

There were financial considerations to that question. District voters have routinely invested in technology infrastructure and equipment through bond issues. In 2009, a $112.5 million bond was approved by voters that set aside $28.5 million for technological improvements. The economic environment meant those technology funds would need to sustain the district for the foreseeable future.

While the auto industry appears to now be recovering, unemployment rates in Macomb County spiked during the recession. UCS students eligible for free- and reduced-priced meals, a common indicator of poverty, jumped from 18.1 percent at the start of the 2008-09 school year to 28.8 percent in 2012-13.

While the district’s financial situation was changing, academic changes were also on the horizon, in the form of the coming Common Core State Standards. As kindergarten expanded, Superintendent of Schools Dr. Christine Johns knew the initial cohort of approximately 2,000 students, who would begin their K-12 education with the new standards, would have to start off on the right track.

“Early childhood education makes a significant difference,” she said. She shared with teachers: “you’re going to give kids the right start. You’re going to set the pace for the school district for the next 13 years.”

So, realizing her youngest students were entering a more rigorous educational landscape, Dr. Johns and a team of influential faculty members decided to act.

“We were leveraging one opportunity I will never be given again,” Johns said.

Instead of purchasing devices or digital content first and then creating an academic initiative around it, UCS wanted a plan that considered the input of many stakeholders, and prioritized goals, learning outcomes, and personnel over hardware and software. That approach incentivizes technology providers to collaborate with the district, rather than simply sell a preexisting product. Similarly, a thoughtful, inclusive planning process would help gain buy-in among faculty and ensure representation of multiple perspectives.

In 2011, Dr. Johns convened an advisory committee to design the new kindergarten program. The 21-person group consisted of eight administrators from the district and building level, and 13 teachers, including “internal consultants” — teachers the district put on “special assignment” to work on the project.

Some initial goals emerged. UCS decided the more differentiated instruction could be, the more personalized each student’s education could become. Instead of teachers developing the same lesson for an entire class or having a limited window into how students are doing, UCS sought an environment where teachers could use a variety of interactions to meet students where they are.

The committee began studying blended learning, examining resources like “Disrupting Class” and “The Rise of K-12 Blended Learning,” speaking with education innovation experts, and reviewing models from other schools, including KIPP Empower Academy, in Los Angeles, and Napa County Schools. They saw promise in models where students could learn independently, collaboratively, and on a teacher-guided track toward mastering the skills they need for the future, with technology collecting data and feedback that helps educators decide what’s best for each student. With a range of tasks and modalities, students work in a way that translates to the real world, Dr. Johns said.

To ensure teachers were the lynchpin of this new model, the committee held an open forum for the district’s kindergarten teachers, from all 83 classes and 25 elementary school buildings, early on in the planning process. Dr. Mary Johnston, the UCS executive director of Innovation, Federal and State Programs and Curriculum, said teachers were enthusiastic about becoming part of the redesigned kindergarten model even if they had limited experience to blended learning concepts.

When kindergarten students begin class, they first check for their assigned group and initial rotation. Student groupings are determined by the teacher, based on focus areas informed by Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA) assessment results, academic performance in adaptive software, and the teacher’s own judgment. Teachers take some creative license in how to start the class and signal the rotations, but in each class students learn at a variety of centers based on their personalized lessons.

Typically in groups of six, students work on MacBook Air laptops using DreamBox Learning, a math program for grades K-6. UCS selected DreamBox based on teacher recommendations and screenings of many other courseware options. DreamBox was selected because it offers detailed data reporting for teachers and parents and presents math as a manipulative task, rather than a formulaic one. Students solve problems through spatial relationships and processes instead of memorization.

“We grew up with the ‘steps’ to make math work and didn’t really understand what was happening to the numbers”, Meyers said. “But with this real-world focus on core mathematical practices, it is about the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of math.”

Usually in groups of six, students work on math and literacy lessons through eSpark, a Chicago-based software provider that designs math and reading lessons around vetted, third-party videos, eBooks, and apps on the iPad.

At the beginning of the year, students take a pre-assessment through NWEA to “diagnose student learning needs and create a personal learning profile for each student.” NWEA’s MAP assessment is online, adaptive, and incorporates the Common Core State Standards.

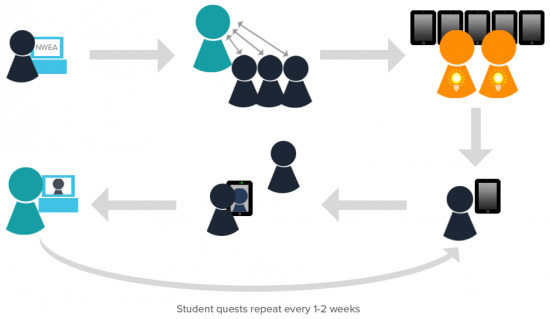

Based on those results, teachers work with each student to identify goal areas in literacy and math, allowing eSpark to select and add personalized apps to each classroom’s iPads. eSpark gives each student lessons called “quests,” which are based on a specific academic standard.

Each quest begins with a short quiz and introductory video, during which students are instructed to complete lessons in the third-party apps uploaded to the devices. At the end of each “quest,” students record a video on the iPad in which they explain what they learned in the lesson. The video is stored in an online dashboard teachers can access.

All classrooms feature an interactive whiteboard that offers digital lessons and activities for students to complete individually and in small groups.

This center features collaborative activities like manipulatives, building blocks, storytelling, and other tasks.

For this center, students are individually selected to work with teachers in groups of one to four – for targeted, focused instruction based on students’ needs.

How teachers decide to target students for direct instruction varies from classroom to classroom. For instance, Maureen Langenderfer, of Wiley Elementary, makes sure all students are at their assigned stations and then pulls a small of group of students to work with her directly. Other teachers, like Kristen Frazier at Beacon Tree Elementary, move from station to station and respond to any questions or problems that may arise.

While some models are based around entire class periods, at UCS those transitions tend to happen every 15 minutes, an interval informed by brain research into young children’s ability to focus. Given the frequency of rotations, the model allows movement and interaction to become vehicles for learning rather than hindrances to it.

“We didn’t want to just say, ‘OK iPads are new, we want to get them into the classrooms,’” Dr. Johnston said. “We were really looking for what tools will help us achieve that customized, individualized pathway for learning.”

Students progress through the digital curriculum at their own pace, in some cases completing the equivalent of a kindergarten curriculum before the end of the year. In many classrooms there are charts on the wall showing how students are progressing through the standards delivered through DreamBox. At West Utica, a student earns a virtual award – a simulated scoop of ice cream – for every goal reached. Similar progress markers for vocabulary lessons and math concepts are tacked along the walls.

A center-based approach to kindergarten isn’t entirely new, but the blended model offers more consideration for each individual student’s needs and adds the value of technology that can assess performance, focus, and growth. In Frazier’s class, her own desktop computer is usually open to her DreamBox dashboard showing in real-time which students are on task and which are struggling. Out of class, teachers can dive into data reports to view student progress over longer periods of time; similar reports are sent to parents.

Citing the difference between whole-class instruction and the smaller group approach, Meyers said, “There is no teacher that will tell you it’s better to teach 24:1 than 6:1.”

Initially there were concerns that technology would disenfranchise the teachers or that the new model would make obsolete the skills those successful, veteran teachers have built during their careers. But the new approach, with its continuous feedback loop and differentiation, actually magnifies what good teachers do best: prescribing what’s right for each student.

“With this model, students get the best of both worlds,” Meyers said. “In the stations, they have a digital curriculum that gives them immediate feedback and meets them at their own level. And in small groups, they get guided, intense, instruction by a skilled teacher.”

For some teachers, Dr. Johns said, the significant changes — moving to an all-day format, adding 12 devices to each classroom and asking teachers to use a completely new method of instruction — significantly altered their idea of kindergarten. As such, one of the district’s top priorities is to make sure teachers are integral to the program’s development, Johns said.

In addition to elevating the teacher voice during the planning process, UCS wanted to provide professional development that actively involved their teachers in a reimagined kindergarten program. Just as students’ learning would be personalized and blended between online and face-to-face environments, so would teachers’ professional development.

“Because this is probably one our largest initiatives, at such a grand scale, we knew we had to invest in professional development for our teachers to support them along the way,” said Einhaus.

In the spring and summer of 2012, UCS gathered all kindergarten teachers for intensive, whole group sessions to explain the new model, the research behind it, and the teacher’s role. The district, along with representatives from its technology providers, presented multimedia examples of what the classroom would look like. Teachers then brainstormed how to apply that model to their own classroom, with a focus on practical issues like scheduling, lesson planning, and feedback.

That work continued beyond the districtwide sessions. An instructional coach followed up with each teacher to discuss implementation. Each teacher received an iPad to take home for the summer and was placed into a Professional Learning Community with peers from across the district.

Online, teachers use Edmodo to ask questions of practitioners inside and outside the district and share lesson plans, ideas, and challenges they face. Teachers can post and view videos of each other using the new model in the classroom. That online activity carries over into the real world, where teachers meet face-to-face with other members of their PLC and with advisors like Meyers. They also participate in monthly in-person, half-day sessions within the district. And for any technical problems they run into, teachers can call a 24/7 troubleshooting hotline.

Just as teachers started with varied knowledge of instructional technology, they progressed at different rates throughout the first year as well. At a time of a statewide change in an evaluation process, UCS gave its teachers the flexibility to test ideas that would take the innovative program to a higher level.

Any fears that technology will replace teachers appear to have given way to empowerment; teachers interviewed said they are given more information on each student and are trusted to use it.

“I feel more personally involved with them,” said Langenderfer, who has taught for 20 years. “I actually have more time with each student.”

As prepared as the teachers may have been, UCS knew the implementation of its blended kindergarten would suffer without the proper technological infrastructure and management in place.

Incidentally, UCS laid the groundwork for blended kindergarten nearly 10 years ago, as it tried to move ahead of the curve — and ahead of demand — of technological requirements. UCS became one of the first districts in Michigan to offer wireless internet system-wide and an upgrade in the summer of 2012 further readied UCS for its new initiative. Now, all students can be active on instructional apps and still have access to high-speed internet. Overall, the infrastructure and hardware costs associated with the blended learning kindergarten program exceeded $2 million, sourced through the bond issuance.

“We’re planning for the years ahead,” said John Graham, executive director of information technology at UCS.

But what of devices? Scaling 1:1 environments can be difficult for districts of Utica’s size to sustain financially over the long term, especially without doing so at the expense of teacher and student support. The district created a financial model where learning outcomes took precedence over hardware.

UCS decided to prioritize and invest funds in professional development– $250,000 over multiple years–rather than devices for every student. Instead of truly 1:1 learning, the planning team created a model that called for each classroom to receive six iPads and six Macbook laptops. While the $440,000 UCS spent on instructional content and assessments is covered by the district’s general funds, the devices are covered by the bond issuance.

Still, UCS faced another challenge: how to manage and procure apps for devices in 83 different classrooms, for nearly 2,000 individual students. With iPads, there are tens of thousands of educational apps available and many district leaders are hard-pressed to determine which are reliable and then how to procure them at scale.

The district is partnering with eSpark to ease those processes. The teachers are able to match apps to students’ individual needs with prescriptive apps preloaded on each iPad. That process was initially done by hand with three-day on-site sessions at UCS; with eSpark, this process has since been automated. As a result, the district has access to a wide variety of educational apps while dealing with only one vendor and signing only one contract. The district receives discounts through Apple’s volume purchase program to pay for the extra third-party apps.

Because the app selection is adaptive, the “course materials” available to schools are constantly changing based on NWEA assessment results, teacher feedback, usage time, and other factors, with both local and national data taken into consideration. During the first year in UCS, there was a significant percent turnover among recommended apps in eSpark, said the company’s CEO David Vinca. That’s a sharp contrast to the arduous, multi-year process of reviewing and piloting print curricula, Dr. Johns noted.

As eSpark works with third-party apps, the data reporting for teachers isn’t as extensive as DreamBox. But based on recommendations by teachers, many from UCS, the company is adding its own pre-assessments to all of its lessons so teachers have more frequent performance data than the NWEA intervals allow.

“They are not the provider that arrives, sells us a product and they are gone,” Dr. Johns said. “When we say there’s a problem, they are here and they are in the trenches problem solving with us.”

The relationship benefited eSpark as well. Its contract with UCS is one of its largest to date. For a small, 34-employee company, the close relationship with a school district helps in developing more valuable and sustainable products and services, Vinca said.

In environments that offer self-paced learning, there still must be ready intervention when students’ pace stalls. For the most part, students observed were capably dexterous when navigating through the devices’ operating systems. But some occasionally had trouble finding their way to the third-party apps recommended through eSpark.

UCS had to put in antidotes for making sure students are able to use the technology appropriately. For instance, one student navigated to the correct app — a game where students must rapidly select like terms that appear on the screen to propel a rocket into the air — but ran into a technical glitch. He tried to swipe the rocket along the course and it repeatedly crashed.

To address this issue, students are encouraged to call for the teacher if the software they are using isn’t working or difficult to understand. More broadly, teachers receive student usage data from eSpark, DreamBox, and third-party apps, indicating whether they are on task. In DreamBox’s teacher dashboard, real-time signals note when students are off task.

And students will even help others who are having technical issues. Collaboration is an important part of the model, and some classrooms have designated technology experts to assist their peers.

Students do not take home the electronic devices, but many access DreamBox on their own after school and on the weekends, according to parents, teachers, and the students themselves. At West Utica Elementary, where 70 percent of students are eligible for subsidized lunches and 20 percent are English-language learners, focused efforts are being made to ensure families are aware of discounted opportunities for internet access in their homes.

The principal, Bradley Suggs, has seen the direct benefits of personalized learning for his students. After his own daughter’s progress on DreamBox Learning impressed him, he decided to begin his first-grade students on the software during the tail end of the 2011-12 school year, ahead of the districtwide rollout. At West Utica, each student spends 100 minutes per week using DreamBox, often on stools set up in the school media center (Suggs dubbed the arrangement the “Math Café”).

UCS is confident in the blended learning kindergarten program, seeing promising results from year-end NWEA assessments (note: NWEA is not required by the state). After beginning the year two to five points below the national NWEA average, UCS finished the year 11 – 14 points above. NWEA percentiles are based not on raw scores but expected growth (as determined by historical data), which means UCS kindergarteners are not just outperforming national averages, but improving at a faster rate.

Those gains are larger in areas that correspond with the goal areas each student is given by eSpark. On average in those areas, UCS students improved at a rate 67 percent higher than expected by NWEA, suggesting that the targeted instruction provided by teachers is allowing students to demonstrate improvement in areas where they previously struggled.

In terms of pure growth, those rates were fairly consistent among all learners, including English-language learners and students eligible for free and reduced-priced meals.

Beyond those results though, Dr. Johns is equally cognizant of the reaction of her teachers and families. UCS is a close-knit community that supports its schools; it is important to Dr. Johns that the shift to blended kindergarten earns that support too.

This level of support was evident on a recent night at Havel Elementary, where parents, students and staff braved a cold, windy night to demonstrate classroom learning for a Board of Education Curriculum Night.

Sixth-graders showed off a roller coaster they constructed that used centripetal force to continuously propel a metal ball throughout the track. Fourth-graders exhibited real-life lighthouses they researched and the replicas they built–complete with working circuits.

As the night winded down, Havel students held a play for the attendees that packed the school’s auditorium. With some script-writing help from their teachers, the students staged a show where a magic genie created the perfect school–one with “differentiated instruction” and “skills to be successful in the digital world.”

After the play ended with a drum line performance and students touting the school’s academic performance, the students closed with a literal symbol of the digital transition at UCS. Five students first lined up facing the audience, each revealing an Etch-a-Sketch displaying the letters of their school’s name– “H-A-V-E-L.” Then they discarded their parent’s classic toy and spelled out the school’s name again, this time with a modern one of their own: an iPad.

Text:

Jason TomassiniVideo:

Courtesy of Discovery Education and Utica Community SchoolsPhotography:

Jason Tomassini

Graphics:

Jenny Shin

Contributions:

Nick Pandolfo, Shirley Park