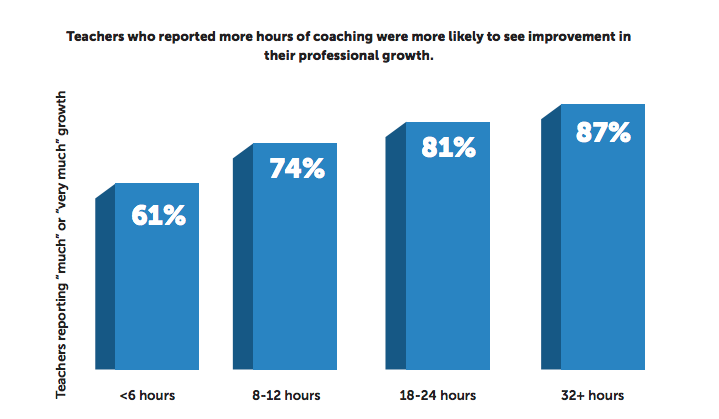

A sustained approach in coaching serves as the cornerstone for the execution of three other tenets of effective coach-teacher collaboration (i.e., partnership, personalization, and active learning). When coaches and teachers have the chance to collaborate regularly and continuously over a period of time, it provides them with the necessary time to establish a shared vision, expectations, commitment, and responsibilities. A sustained approach also helps coaches build a deeper understanding of teachers’ needs, style, and attitude, and therefore more effectively differentiate their support. Moreover, frequent and consistent practice, feedback, and reflection time helps teachers accomplish complex, long-term goals with multiple checkpoints, and become better aware of what they have learned and how they will apply their learning. Research on the Dynamic Learning Project pilot (DLP)1 shows that the more coaching activities are sustained and intensive, the more likely that teachers adopt new teaching practices at a higher degree of quality.

We recommend four strategies that administrators and coaches can consider to facilitate sustained coach-teacher collaboration:

It is critical that the coach’s role be protected to ensure that the majority of the coach’s time is spent directly with teachers for the purpose of coaching. While coaches may be responsible for a variety of tasks both within and outside the classroom, coaches should not be weighed down by administrative or teaching tasks that are not related to their main coaching responsibilities.

At smaller schools, coaches are more likely to be able to provide sustained support to a larger proportion of teachers without sacrificing their depth. However, in larger schools the dilemma of depth versus reach can be more pronounced. In some of the DLP’s large campuses, teachers who were coached for longer periods sometimes referred to themselves as “fortunate,” recognizing that not all of their colleagues were able to benefit from the same amount of support. At the same time, even on small campuses, demand for the support of a coach can exceed supply.

Our data shows that during a 6-to-10 week coaching cycle, a teacher should be able to spend at least 30 minutes one-on-one with the coach every week to see the greatest value. School and district administrators should assure teachers that time spent with their coach during the school day will be protected.

Having shared goals and an action plan to use as a coaching roadmap helps ensure regular and continuous interactions in the coach-teacher collaboration. Shared goals are important in coaching because they give the teacher and coach a common place to start the coaching work. Once the goal is established, coaches and teachers need an action plan in their collaboration to ensure that the bulk of their time together is spent on high-leverage activities. When teachers feel that every interaction with their coach is bringing them closer to realizing their goal, they are more likely to prioritize time for collaboration and keep momentum moving.

We want to hear from you!

Please take this 5-minute survey and help us serve you better.