The average teacher spends 10 percent of a typical school year participating in professional development (PD) activities. However, few teachers are highly satisfied with their current PD, and multiple studies over the past decade have revealed that many PD offerings are ineffective in improving teacher practice. Common sense suggests that educational and instructional programs and practices that are designed based on how the brain works should be more effective at supporting learning. USC Dornsife’s Brain and Creativity Institute recently identified two neurobiological findings about how the brain works; based on this knowledge, the Dynamic Learning Project pilot (DLP)1 research study helps explain why—compared to traditional PD models—coaching could be more conducive to teacher learning and growth.

New evidence on brain functioning shows that it is neurobiologically impossible to devote full attention to completing a concrete task while also reflecting and interpreting what that task means more broadly. In fact, the brain networks controlling outward attention and inward reflection are not the same, and thus, are not simultaneously active. The neural network that supports conceptual understanding, creativity, and big-picture thinking is relatively inactive during task-oriented, context-specific practices that require maintaining attention in the environment, such as listening to the instructor lecturing. That said, these two brain networks are likely linked together and do not develop independently from each other. They are interconnected and closely regulate and grow in a delicate balance. The overall cognition power can be negatively impacted without proper balance between these two networks.

This neurobiological evidence implies that in order to optimize learning, we all need downtime and time for reflection. Educational and instructional practices that spend a lot of time on task-oriented activities without enough opportunities for meaning-making may undermine cognition. Lecture-based PD workshops may be incompatible with how the brain operates. This could explain why these types of workshops have not shown desirable impact on teacher quality, as teachers need focused opportunities that assist them in deeper engagement with the broader meaning of their teaching practices and strategies. These opportunities can facilitate their intellectual investment in their daily tasks and, therefore, are more likely to produce enhanced teaching skills.

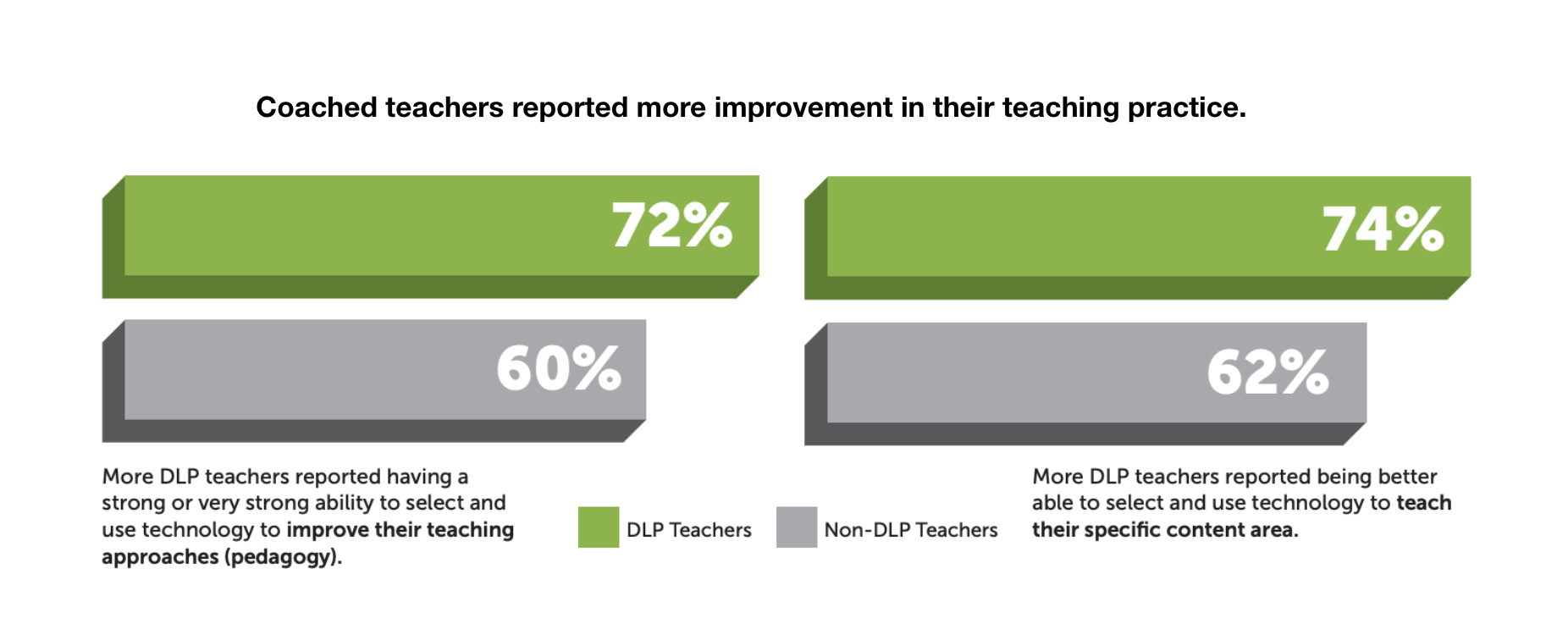

Instructional coaching programs hold significant potential to provide such opportunities for deeper engagement and interpretation because they can be integrated into the daily life of teachers at school and create a balance between action and reflection. Our research on the DLP teacher coaching program suggests that teachers who worked collaboratively with their coach in identifying, tackling, and reflecting on their current classroom challenges reported more improvement in their teaching practices, compared to teachers who didn’t receive coaching. Teachers in our study told us they were more likely to buy into a PD that empowered them to reflect on their challenges in a way that was relevant to their background, experiences, skills, goals, and classroom context. Classroom visits by the coach for co-teaching or modeling as well as regular formal and informal meetings between the coach and teacher before and after these visits are examples of coaching activities that can provide teachers with a variety of opportunities for constructive reflection.

Quite contrary to the traditional belief that emotion interferes with logical reasoning, recent neurobiological studies show that the human brain is fundamentally emotional and cannot engage in thinking and meaning-making without involving emotion, sociality, and cultural experience. The reason emotions and the socio-cultural environment are so powerful is that they are intertwined with our cognition. In fact, emotion and cognition are controlled by the same neurosystems in our brain, as Mary Helen Immordino-Yang explains in this TedTalk.

Neurobiologically, it is not possible to switch emotions on and off. Emotions are central in cognition. They are an integral part of learning and steer the way we think and make meaning out of our experiences. The level of engagement in a learning activity depends on how much we can make emotional connections with that activity. Emotions, such as satisfaction, interest, and sense of efficacy, can affect our learning positively, while stress and frustration can undermine intellectual contribution.

Taking this into account, PD initiatives should strategically consider and use the emotions teachers have about their tasks and environment to support changes in their practices. PD models like coaching that have a direct, sustained connection to teachers’ students and classrooms can be more effective because they can provide support for the emotions teachers experience related to their practices (e.g., stress or excitement). Coaching may stimulate more intellectual and emotional investment among teachers, further helping with teachers’ professional growth and well-being. After participating in DLP coaching, teachers felt less stressed about their tasks. They reported more improvement in their practice than teachers who didn’t receive coaching.

With emotion and cognition so intertwined, it also suggests the importance of recognizing the emotions a teacher has about a PD activity in the design of learning opportunities to motivate teachers’ participation and engagement. For example, our research study showed that teachers who reported non-judgemental coaching were more willing to participate and more likely to report progress in their practice. When teachers trusted that the collaboration with their coach was not evaluative, they worked with their coach in an open and transparent manner. This non-evaluative support provided a framework within which teachers felt free to experiment, take risks, and try new things.